Psilocybin, the active component of “magic” or psychedelic Psilocybe cubensis mushrooms, may soon become an FDA-approved medication. It’s already been decriminalized in Denver, Colorado and effectively decriminalized in Oakland and Santa Cruz, California. But what, exactly, is this compound, and how does it alter the way we think, feel, remember, and perceive?

Chemists categorize psilocybin as a tryptamine compound (hence the experience from it is called a “trip”), though anthropologists classify it as an entheogen. Entheogens are a group of substances that facilitate mystical or spiritual experiences. Although scientists are currently studying psilocybin as a psychiatric medication, it boasts a centuries- if not millennia-long tradition of use in spiritual rites and religious rituals. According to the Global Drug Survey and the latest research from King’s College London, psilocybin is one of the safest — if not the safest — psychedelic drug known to humanity.

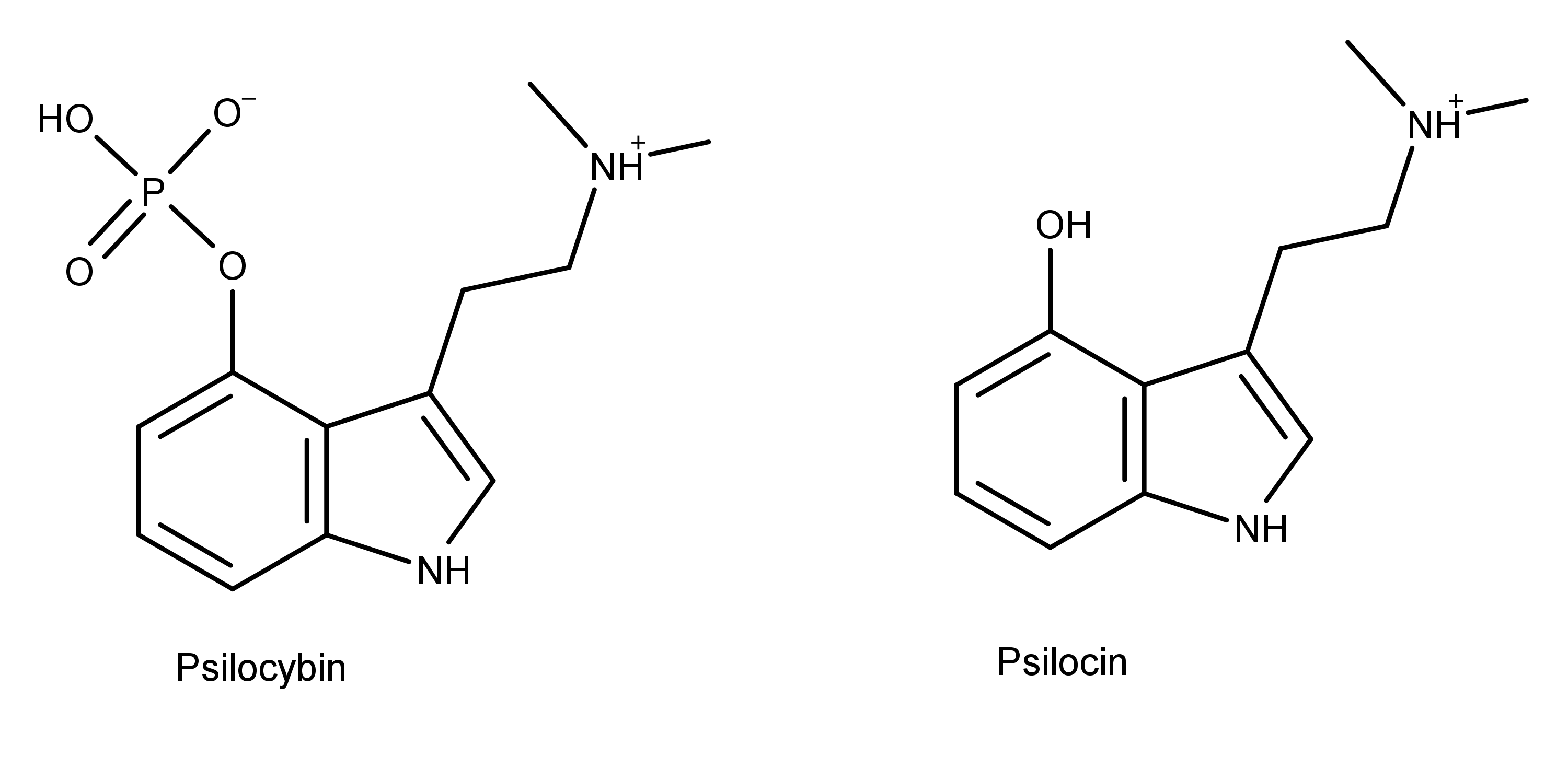

Psilocybin is actually a prodrug, meaning it’s not the compound that makes us trip. Rather, when someone consumes psilocybin, the acids in our stomachs convert psilocybin into another chemical called psilocin. Psilocin — not psilocybin — alters signaling in our nerve and brain cells, triggering shrooms’ psychedelic experience. A psilocybin (or, technically, psilocin) trip can last anywhere from four to 12 hours, depending on an individual’s tolerance and the dose.

(And if you’re wondering why scientists and shroomers alike are always talking about psilocybin and not psilocin, that’s because psilocin is incredibly unstable. If someone gave you a pill or vial of pure psilocin, light, water, oxygen, and ambient heat would degrade it in a matter of days, if not hours.)

The molecular structures of psilocybin and psilocin. The only difference between them is psilocin lacks a phosphate group.

How (We Think) Psilocybin and Psilocin Work

OK, so this is where shit gets technical.

Since the US government considers psilocybin a Schedule I drug, research on it has been extremely limited over the past few decades. Schedule I is the most restrictive drug category in America, reserved only for “dangerous” and “addictive” drugs that supposedly lack any accepted medical use, like heroin… and marijuana. *Eye roll*

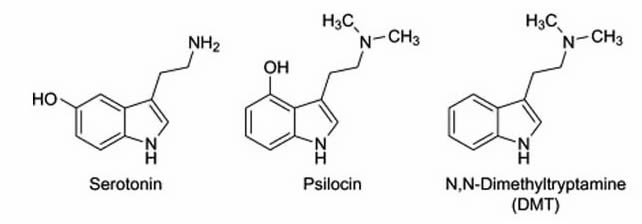

Over the years, however, scientists have gotten some clues as to how psilocybin causes hallucinations, sudden insights, and profound leaps of logic. As described above, when someone eats some shrooms, psilocybin converts to psilocin in the stomach. Psilocin then enters the bloodstream where it binds to serotonin receptors, which are primarily located in the digestive system (though some are in the spinal cord and brain, too).

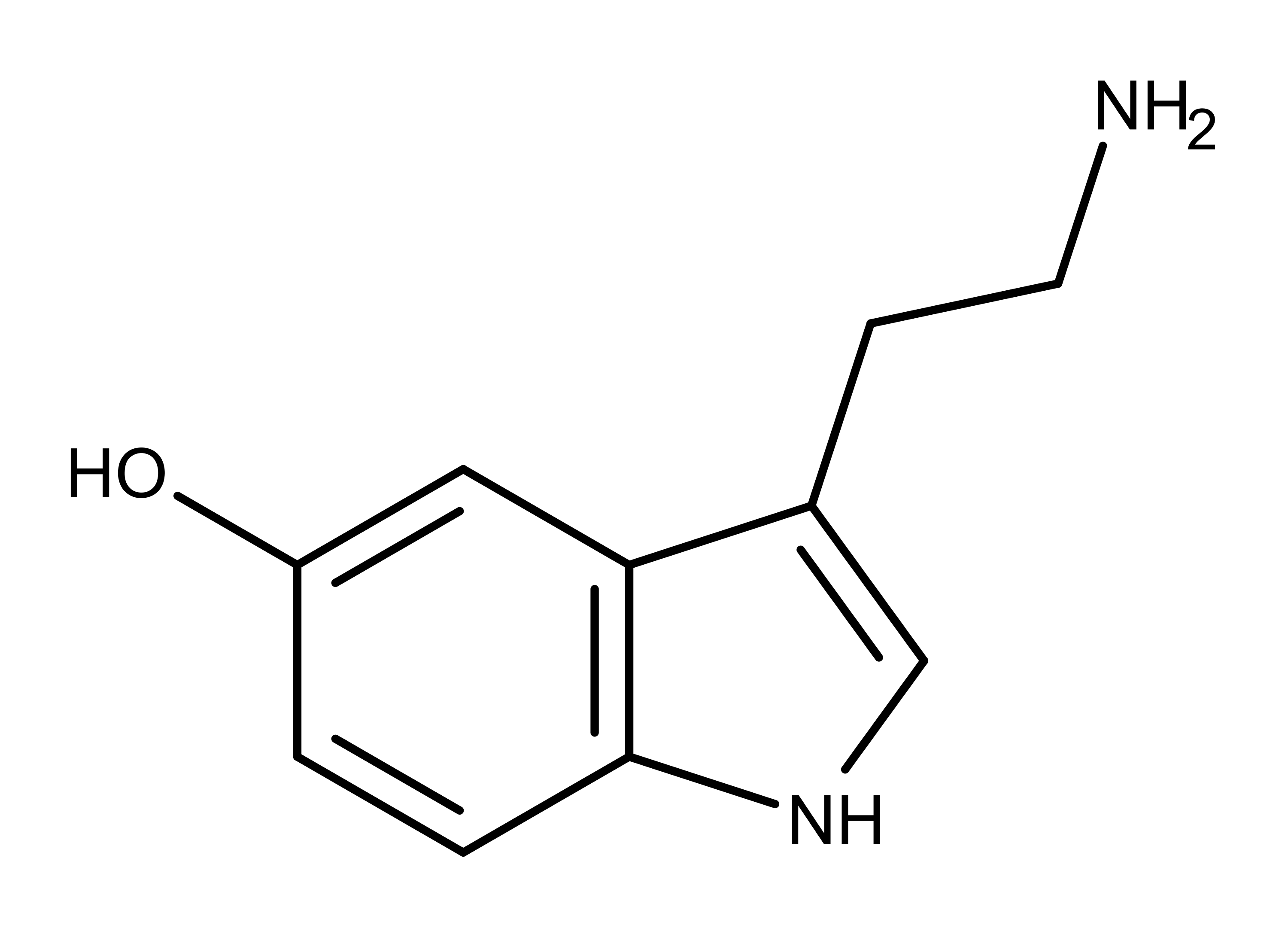

The molecular structure of serotonin, a major neurotransmitter.

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter, meaning it transmits signals through our nervous system. It’s another tryptamine, so it shares a similar chemical structure with psilocybin (and psilocin… and LSD, and DMT, too). Serotonin is responsible for regulating our hunger, sleep cycles, feelings of happiness and well-being, reward reinforcement, memory, body temperature, sexual desire, and — apparently — our visual perceptions. Psilocin binds and partially activates the same receptors that serotonin does, which causes dopamine to flood our system, as well.

And that’s about the gist of what science understands about psilocin’s psychoactivity. How all these neurotransmitters contribute to and influence our mental states is still being worked out, as psychopharmacology is one of the youngest sciences in existence.

But How Does Psilocybin and Psilocin Ultimately Affect Our Brains?

Although the psilocin trip only lasts a few hours, research suggests the compound’s physical effects on our brain may last much longer, up to five years from just a single dose. This research lends some credibility to the “Stoned Ape Theory” developed by late philosopher and psychonaut Terrence McKenna, who believed that humans evolved from simple cave dwellers to a thinking species that produced complex art, music, tools, and culture after imbibing in psychedelics like psilocybin. However, most anthropologists don’t agree with McKenna’s theory and consider it pseudoscience at the moment.

Now, how psilocin physically changes our brains remains a mystery. But brain scan studies from Yale University and the University of Zurich suggest that the psilocin trip creates new neural connections in the brain. Basically, parts of the brain that don’t normally communicate with one another start chatting it up non-stop, like co-workers who work in different departments and are meeting each other for the first time at a company party. After the trip subsides, these new connections mostly go away, but some of those connections remain in place, possibly forever.

If people suffering from mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, PTSD, or anorexia are suffering because of miscommunication in the brain, then psychedelics such as psilocybin or psilocin could restore or enhance brain function in ways that current medications and surgeries cannot. This is why psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, which includes other outlawed drugs like MDMA (ecstasy or molly), LSD (acid), DMT, ayahuasca, and “toad” could revolutionize modern medicine, as well as end the stigma against these powerful, potentially life-saving, and relatively non-toxic substances.