We’ve come a long way since the ‘90s, when California passed Proposition 215: the nation’s first statewide medical marijuana law. But as CBD becomes available in every corner store, canna-stocks take over Wall Street, and questions about weed spring up on Jeopardy, it’s easy to forget how and why the cannabis movement initially began.

Remember, it took off during the AIDS crisis.

The story begins in California, where Dennis Peron, a gay man dubbed the “father of medical cannabis,” saw many of his friends die from AIDS. The epidemic wiped out thousands, and cannabis was among the few remedies that provided the suffering some relief. But the drug laws of the time showed no mercy. If an AIDS patient was caught using weed by law enforcement, the patient was arrested and put in jail — where the level of suffering increased.

The unjust fuckery inspired Peron to lead one of California’s most successful advocacy movements to date: the reform of state cannabis laws. Although his activism is legendary, he was just one man, a core piece to a much larger, intricate puzzle of people who are all equally responsible for the success of the cannabis reform revolution. Most stories detailing the movement’s historical developments focus solely on Peron and the passing of his late partner, Jonathan West, in 1990. But in reality, it took a village of people — from every race, gender, socioeconomic and health status — to catalyze the change.

What follows is a history of California’s — and ultimately the nation’s — medical cannabis movement through the lenses of some of Peron’s closest confidantes and protégés, who together composed an army of LGBT activists and their straight allies.

Reagan and the ‘Gay Plague’

In 1981, scientists first identified a new disease that seemed to only afflict gay men. Originally called “Gay-Related Immune Deficiency,” or GRID, doctors initially had no idea what caused it.

In 1983, Larry Kramer, a screenwriter, novelist, and founder of the AIDS activist organization Gay Men’s Health Crisis, appeared on NBC’s Today Show. He asked the show’s host, Jane Pauley, “Can you imagine what it must be like if you had lost 20 of your friends in the last 18 months?”

“No,” Pauley answered.

By the time Kramer appeared on national TV, over 2,000 Americans had died from AIDS. It would be another two years after Kramer’s Today Show interview before President Reagan even said the word “AIDS” in public.

The Reagan Administration took its bittersweet time responding to the epidemic because, as stalwart defenders of Christian purity, it viewed homosexuality as a moral failing. Homosexual behavior was even outlawed in some states and cities at the the time. So the crisis was perceived as a legalistic failing, too. According to Reagan’s cronies, a wasting disease that resulted from gay sex wasn’t America’s problem.

Unlike Reagan’s administration, however, AIDS didn’t discriminate. And it still doesn’t.

The virus initially spread among the gay community, particularly in the San Francisco Bay Area, where queer Americans settled to avoid harassment and ostracization. But once AIDS began killing members of Reagan’s former ilk — like famous Hollywood stars — and HIV appeared in other at-risk groups — like intravenous drug users and hemophiliacs — the American public finally took notice.

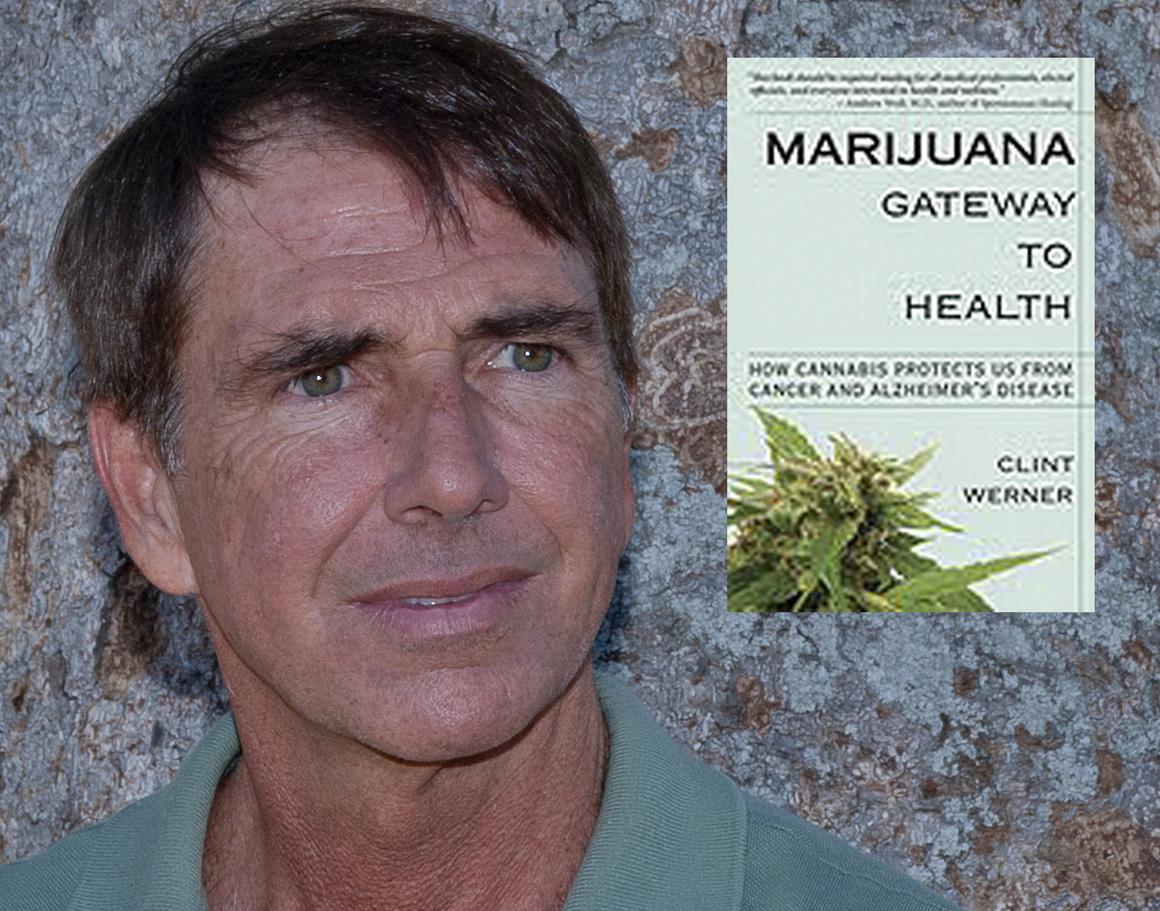

Clint Werner based his landmark book, “Marijuana, Gateway to Health,” on his experiences helping cancer and AIDS patients in California.

The Sacred Band of Thebes: Clint Werner and Dr. Donald Abrams

Although many of California’s queer weed activists are no longer with us due to the AIDS epidemic, some still are. Clint Werner is an author and cannabis activist based in San Francisco. In 2011, he published the book Marijuana, Gateway to Health, which compiled the most up-to-date scientific information on cannabis for that time. It detailed decades of his first-hand experience witnessing the plant’s power, particularly in AIDS and cancer patients.

Werner first came to the Golden State from North Carolina while following the Grateful Dead on tour. But after making the Bay Area his home in the late ‘80s, he got a front row seat to what he describes as a real-life “horror movie.”

“Young people today have no idea of the trauma — the horror — of seeing AIDS patients walking up and down Castro Street, looking like extras from some war film or horror movie; gaunt [and] their skin covered in Kaposi’s sarcoma splotches,” Werner told MERRY JANE over the phone. “Men with canes, 35-years-old looking like they were 80. It was insane. It was the most horrible thing.”

Without any medical guidance, the gay community resorted to an array of unconventional treatments, which is what led patients to cannabis. It was the only medicine that relieved AIDS symptoms on several levels: it helped manage the pain associated with chemotherapy treatments that doctors tried off-label on AIDS patients; and it helped restore appetite, even as the disease ravaged patients’ digestive systems.

Werner met his partner, Dr. Donald Abrams — a renowned integrative oncologist at the University of San Francisco, who was among the first to study the impact of cannabis on AIDS — at a MAPS conference in 1994. It was there that Abrams publicly discussed his work on AIDS and medicinal cannabis, two new medical arenas wrought with controversy.

.jpg)

Dr. Donald Abrams, in previous interviews, has said that he always recommends medical cannabis to his patients.

After the American public began learning about medical cannabis as an AIDS treatment, MAPS founder Rick Doblin saw that the cannabis iron was scorching. He coordinated with Abrams to devise a study to definitively show that marijuana was a valid medicine. But with the plant’s Schedule I standing — and George H.W. Bush in office — getting the federal government to sign-off on the study was beyond difficult.

In 1995, Abrams requested permission from the DEA and the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) to test medical marijuana’s effects on AIDS patients. NIDA rejected the proposal because federal agencies wouldn’t support any research that might show the medical benefits of an illegal narcotic.

Abrams’s hospital supervisor cautioned him against performing the study because it could wreck his career. So Abrams sent a letter to Doblin announcing his withdrawal from the project.

“Bullshit!” Werner recalled saying to Abrams. “Bull. Shit. What the fuck are they gonna do to you? You’re freaking Donald Abrams. They’re not going to fire you just because you submitted a protocol.”

Persuaded by Werner, Abrams revised the proposal to appease the powers-that-be. He tweaked it into a “safety assessment study” rather than one intending to show the medical benefits of the plant.

Everyone prepared for another round of disapproval.

But the strategy worked. Abrams reframed his proposal so it looked into the interactions among smoked marijuana; dronabinol, a synthetic THC pharmaceutical; and the investigational drug Indinavir in AIDS patients. In 1997, NIDA finally approved the study and provided Abrams a $978,000 grant.

That same year, Abrams and the National Institutes of Health held a press conference to announce the project. Mainstream media brought additional attention to the issue, and American discourse slowly began to shift from weed being a drug that ruined lives to a natural remedy that relieved suffering in the terminally ill. Abrams also went public with how difficult and slow it was to receive approval for the study, while the government gladly expedited anti-cannabis research grants.

In 2000, Abrams and MAPS finally concluded the project and released the results. Ultimately, the study not only showed that smoked cannabis was a safe treatment for AIDS patients, but also that it could reduce HIV’s progression against the immune system. Other states took note: between 1997 and 2000, Colorado, Nevada, Maine, Hawaii, Alaska, Oregon, and Washington state joined California by legalizing medical marijuana.

Clint Werner with the illustrious Brownie Mary at Dennis Peron’s San Francisco Buyers Club, circa 1993.

The Sparks That Lit a Nation on Fire: Brownie Mary and Dennis Peron

But while Werner and Abrams worked to prove the scientific benefits of cannabis, Mary Jane Rathbun, better known as “Brownie Mary,” fought for medical cannabis in a different way. An activist in San Francisco, Brownie Mary earned her nickname by handing out infused brownies to those suffering from AIDS while volunteering at San Francisco General Hospital’s AIDS ward.

Brownie Mary, who died in 1999, was one of the first cannabis activists to rise out of the ‘60s and ‘70s. While waitressing at IHOP, she perfected the art of baking “magical” brownies and sold them in the Castro District, San Fran’s historically gay neighborhood. So by the time AIDS ravaged San Francisco, Brownie Mary was already known as the Betty Crocker of laced treats.

And the cops knew it. Brownie Mary was arrested three times — all of which garnered massive media coverage, particularly due to her “little old lady” appearance and (contradictory) illicit behavior. Her third arrest, however, was the most famous and solidified her as a foremother of medical marijuana.

Werner explains that Brownie Mary was arrested by an “asshole, anti-cannabis, anti-hippie cop” notorious for busting defenseless marijuana patients and activists. It’s thought that her arrest may have been retaliation for helping draft Proposition P with Dennis Peron, who was a friend and political cohort of Brownie Mary, Werner, Abrams, and others in the movement.

Prop. P allowed marijuana patients to possess weed and medical doctors to recommend it. But the law was only applicable in San Francisco, and Brownie Mary’s arrest revealed the limitations of the law. She was busted in Sonoma County, just outside of San Francisco’s jurisdiction.

Although prosecutors charged her with two counts of felony marijuana possession, she was acquitted under a “medical necessity” defense. By the time of her third arrest, she wasn’t seen as a “naughty grandma” anymore. She was recognized as an HIV activist fighting for patients’ rights to use and access cannabis. She embodied the compassion that the eventual Prop. 215, also known as the Compassionate Use Act, was founded on, and helped spread the message Abrams, Werner, and Peron also advocated.

LA’s Pride: Paul Scott

At this point in the early ‘90s, Peron was helping nearly 11,000 patients across California. To manage such a widespread network, he needed troops. He needed to show others how to grow high-quality pot, educate the public, and steel themselves against the authorities in the event of a police crackdown.

Among those students was Paul Scott, who described himself as “probably Dennis’s only black disciple.” The two met in San Francisco in the latter half of the ‘90s.

Scott moved to LA with his mother when he was eight-years-old, and still resides in the City of Angels. A former US Navy Corpsman who later became an AIDS ward nurse, Scott founded LA’s Black Gay Pride and served as the city’s County Commissioner on HIV/AIDS from 2002 to 2008. He also owned and operated the Inglewood Wellness Center, a medical marijuana collective, from 1999 to 2013.

Through the Inglewood Wellness Center, Scott helped AIDS and cancer patients understand how cannabis could counteract the disastrous effects of toxic, conventional medications prescribed by doctors. The center brought in patients from all over Southern California.

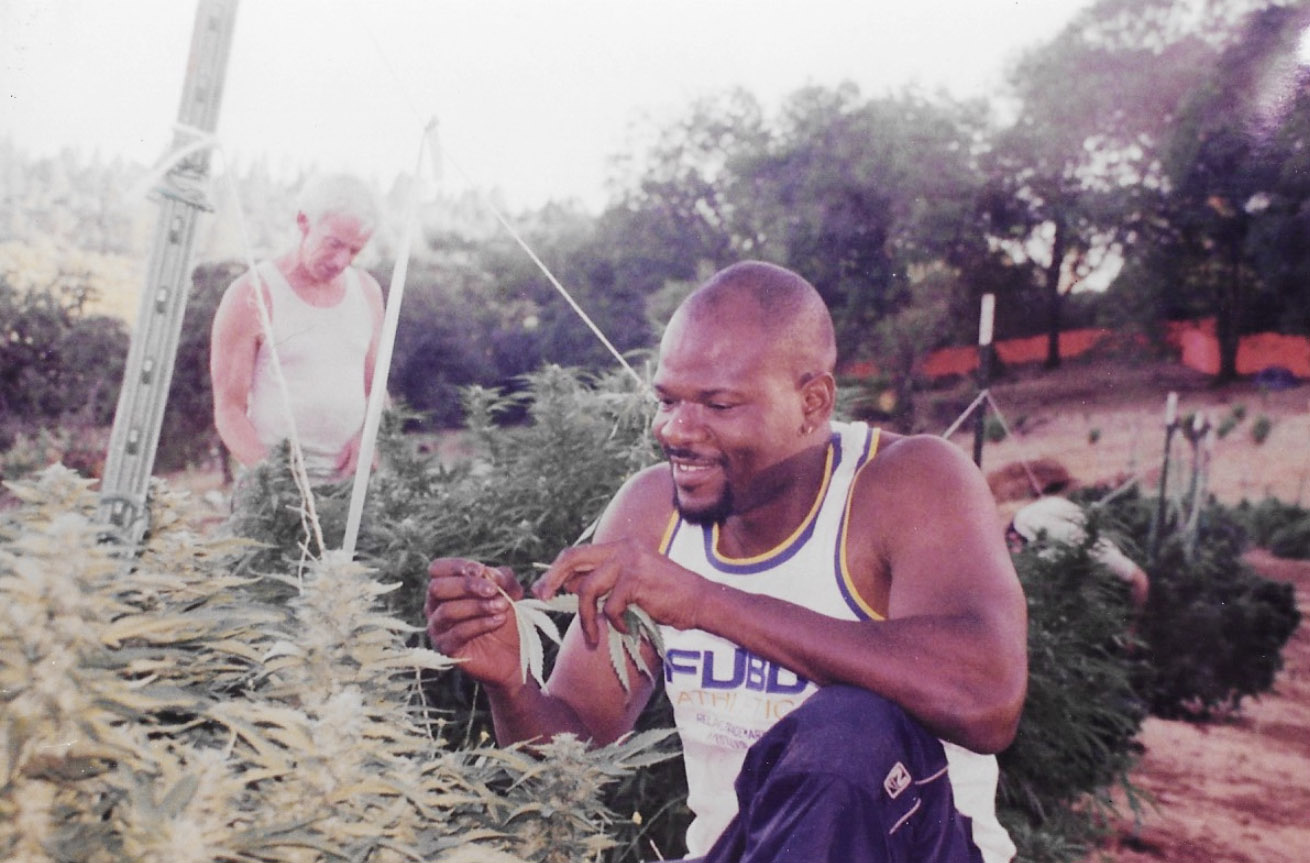

Paul Scott (right) with Dennis Peron at the Big Top Farm

Although the wellness center was raided by cops, and he was arrested on three separate occasions for providing medical weed to sick people, Scott beat the charges every time.

In one instance, a county prosecutor dropped a case against Scott after NORML’s attorneys presented numerous awards bestowed upon him and his wellness center by various city officials.

“I was legitimate, and I was sick,” he said, pointing out that he’s lived with HIV for many years. “I wasn’t a dope dealer.”

This is why Scott insists his Inglewood location wasn’t a dispensary, but rather a tried-and-true wellness center. The Inglewood Wellness Center also hosted support groups for the terminally ill, specifically for straight black men struggling with the realities of an HIV diagnosis.

The Inglewood Wellness Center inspired others to establish similar medical cannabis outlets within city limits, too. After all, if Scott could operate in Inglewood without a license, others could do the same. And they did.

But in the age of increasingly heavy regulations and constant federal interference, Scott shut down his operation in 2013. He has since co-founded ERBA in Los Angeles – ironically, the city he avoided operating in for years – which is still in business to this day.

Andrea Tischler’s famous “Nurse Mary Jane” hat.

Santa Cruz’s Andrea “Nurse Mary Jane” Tischler

While LA was Scott’s territory, San Francisco served as Dennis Peron’s. In Santa Cruz, Andrea Tischler took Peron’s lessons from the Bay Area and applied them to NorCal’s Surf City.

Tischler, a lesbian, was known in the ‘90s as “Nurse Mary Jane.” Although she wasn’t a certified nurse, her partner crafted a nurse hat for her with a glittery pot leaf on it. Tischler then put together a nurse outfit and began visiting patients and attending marches — and dispensing free joints to the sick and needy.

Tischler’s work at the grassroots stage complemented her successes at the legislative level. With activists Scott Imler, Theodora Kerry, and several others, she helped draft and pass the Santa Cruz Medical Marijuana Initiative in 1993. Similar to San Francisco’s Prop. P, the law paved way for the Santa Cruz Buyers Club, the city’s first medical cannabis collective.

“I worked with most of them from the beginning,” Tischler said, citing her alliances with Peron’s crew. “Remember that there were only a few dozen original cannabis activists in Northern California in the early ‘90s who trail blazed the movement.”

From 1995 to 1996, Tischler served as Santa Cruz’s chair for Proposition 215, which legalized medical marijuana across California in 1996. In the 2000s, Tischler and her partner moved to Hawaii, where they’ve since been working non-stop to bring legal weed to the Aloha State.

Members of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a pro-cannabis transgender organization, at a weed conference in 2005. Photo by Chris Conrad and Mikki Norris.

During her time as an activist in California, Tischler noted that the AIDS epidemic didn’t just affect the gay community. It affected the transgender community, too – specifically transgender women.

“Sadly, transgender people were not accepted in the gay community during the ’70s,” she said, noting that some of the first documented cases of AIDS were before the ‘80s. “At a time when gays and lesbians were trying to present themselves as credible, [transgender women] were the ones with the outlandish makeup, bad clothing options, and who were generally unemployable.”

Trans women, outcasted by society at large, often resorted to sex work to make a living, which contributed to the spread of HIV.

“Many of my transgender friends are no longer here, having died in the ‘80s,” she said, “which was well before the medical marijuana movement began.”

But it’s unfair to credit the LGBT+ communities for the entirety of California’s medical marijuana movement. Tischler noted that although Peron’s efforts forever changed the state’s legal and cultural landscapes, he was just one (vital) factor in the much larger, longer campaign.

If she had to pick who made the greatest contributions to the medical marijuana movement, Tischler said she would pick a heterosexual married couple: Mikki Norris and Chris Conrad.

Chris Conrad and Mikki Norris celebrating the passage of California’s Proposition 215 in 1996.

Turning a Miraculous Leaf: Chris Conrad and Mikki Norris

Conrad and Norris’ contributions to the movement are (like everyone else mentioned) too expansive to fit into a single story. Some of their achievements include founding the American Hemp Council, designing and curating Amsterdam’s Hash, Marihuana, and Hemp Museum, and working as delegates to advise the UN on tolerant international drug policies. They were also instrumental in Prop. 215’s campaign.

In 2008, Norris and Conrad co-founded West Coast Leaf, a newspaper that exclusively covered marijuana stories. They retired the print version of the publication in 2013 and brought it to the web as The Leaf Online. (Both Mikki and Chris have contributed to MERRY JANE, as well.)

Conrad, an author and expert witness for criminal cannabis cases, helped edit and revise Jack Herer’s groundbreaking book, The Emperor Wears No Clothes. He also taught weed history and politics at Oakland’s Oaksterdam University, the nation’s first college devoted entirely to cannabis.

Conrad told MERRY JANE that boiling down California’s medical marijuana movement to only the AIDS epidemic doesn’t tell the whole story.

“I agree that the gay rights and AIDS issues were key to getting medical marijuana [legalized],” he said. “But it was actually cancer patients that discovered and disseminated info about medical use on a wide scale, particularly in reference to chemotherapy side effects like nausea.”

Conrad does, however, view the AIDS crisis as the “fulcrum” that forced the movement forward.

“The focus shifted to the AIDS epidemic, and particularly San Francisco, years later when chemo was being used to fight AIDS,” he said. “That’s where the gay community, outlaw growers, and the medical community connected on the issue.”

Chris Conrad and Mikki Norris campaigning for Proposition 215, the nation’s first state-wide medical marijuana bill.

Conrad and Norris both worked alongside Dennis Peron and Terrance Hillinan, another San Francisco-based activist. “While [Peron and Hillinan] became the most visible part of the movement, we were always pitching to people with less flamboyant health problems, like seizure diseases, digestive health, traumatic injuries, et cetera,” he recalled. “Those groups were not as unified or visible, but usage among them grew at a rapid rate, as well.”

It’s important to highlight that the people included in this story are only a few of the individuals involved in making legal weed a reality. Others include Dr. Tod Mikuriya and Dr. Lester Grinspoon, who Conrad said truly kickstarted the movement. Michelle and Michael Aldrich, Randall and Alice O’Leary, John Entwhistle, William Panzer, Thomas O’Malley, Dale Gieringer, Anna Boyce, Leo Paoli, Harvey Milk, Jonathan West, and many, many more all lent their hands to the effort.

Pot Doctors: Dr. Molly Fry (left) with Dr. Tod Mikuriya (center) and Dr. David Berman (right) at California’s annual NORML conference in 2005. Photo by Chris Conrad and Mikki Norris.

No single demographic, organization, or individual can lay claim to the movement’s legacy. It happened because people from all walks of life — white and black and brown, gay and bi and straight, trans and cis, wealthy and middle-class and poor — united on a common front.

“Tragic as the AIDS crisis has been, without it, medical marijuana might not have taken its great leap forward,” Conrad said. “From all that pain has come a great deal of relief to people around the world. One cannot overstate how important that has been for humanity.”

With the passage of Prop 215, and later SB 420 — which clarified the rules set forth by Prop 215 — California became the first US state to wake up from the fugue of prohibition. Without the AIDS epidemic and the LGBT+ communities’ efforts, weed activists — straight or otherwise — may not have had the big push in 1996 that got legislators and the public to treat cannabis as a medicine. Ultimately, it took the bravery of numerous marijuana patients to come out about both their sexual identities and their cannabis use for the rest of the world to finally see that weed could save lives.

Of course, the road toward legalization proved to be a rocky one. Even today, just over two decades since Prop 215’s passage, California still struggles to reconcile its legal marijuana industry with federal outlaw status.

“In America, it’s always two steps forward, one step back,” said LA’s Paul Scott. “Progress in America is slow. It’s always been that way.”

Follow Randy Robinson on Twitter