In a time long before recorded history — perhaps as far back as 100,000 years ago — early hominids, the ancestors of today’s humans, may have evolved smarter, faster brains because they regularly tripped balls.

I’m not making this up. This is an actual hypothesis by Terrence McKenna, one of America’s most influential psychonauts.

McKenna studied ecology, conservation, and shamanism at the University of California-Berkeley’s Tussman Experimental College. Some of the West’s first exposure to the psychedelics DMT and ayahuasca came from his early writings.

A Crash Course on the Stoned Ape Theory

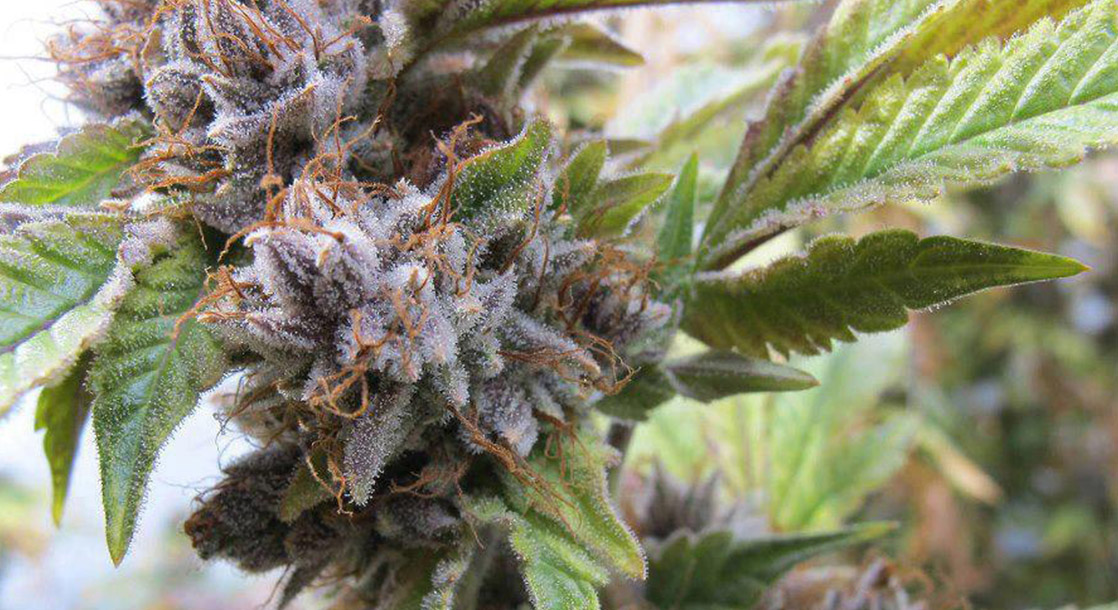

McKenna’s 1992 book, Food of the Gods, first proposed what’s referred to as “the stoned ape theory.” One of our early ancestors, Homo erectus, began eating Psilocybe cubensis — a psychedelic mushroom — as part of their diet. Psilocybe cubensis is often found growing under cow poo, so the theory suggests that hunter-gatherer groups would follow herds, then stumble on the shrooms left in the herds’ wake. Easy pickins, right?

As Homo erectus kept tripping, hominid society became richer and more complex, eventually turning the mushroom-eating into a religious ceremony. There is some evidence that suggests psilocybin can also enhance visual awareness — which would make hunting more efficient — and that it can stimulate sexual arousal, facilitating greater reproduction of babies.

Then, continued ingestion of psilocybin began to fundamentally alter the structures of the early humans’ brains, forming new, vast neural connections where none previously existed. From there, Homo erectus developed art, music, language, poetry, and philosophy. As the species evolved into cultural creatures, accustomed to living in relatively comfortable societies with plenty of foraged and farmed resources, Homo erectus morphed into a new species, Homo sapiens.

Psychedelics and Altering the Brain

Cool story, bro. What’s the evidence?

To be frank, the evidence for the stoned ape theory is scant. Anthropologists, historians, and paleontologists don’t take McKenna’s far-out human-origin theory seriously, namely because it’s not based on much besides the fact that ancient people liked to get high. It probably doesn’t help that the stoned ape theory’s most well-known cheerleader today is podcaster Joe Rogan.

But let’s entertain the theory for a second.

Psilocybin becomes another chemical, psilocin, after being metabolized in the human body. Psilocin is actually what makes us trip, not psilocybin. We know that psilocin pushes our serotonin activity, and serotonin — get this — can permanently alter our genes through a process called epigenetics. And the altered genes can be passed down to offspring, for better or worse.

We also know that psilocin changes the way our brain communicates with itself. Basically, the molecule forces our neural network to expand, temporarily connecting all parts of the brain with itself and the body. This cognitive synthesis is likely how artists birth new ideas while in the throes of a mushroom trip, or why some scientists claim that microdosing psychedelics helps them solve technical problems.

Unfortunately, that’s about where the hard evidence stops. We’ve never observed someone forming entirely new brain structures because they tripped their face off every weekend. And while heavy drug consumption can change our gene expression, there’s no evidence showing that getting high all the time can transform us into a new, more intelligent species.

What’s the Point of the Stoned Ape Theory, Then?

McKenna wove a fascinating story, but he had a political agenda, too. As a psychedelics guru, McKenna believed that the War on Drugs was wholly unjust, and that when governments outlaw psychedelics, they’re not trying to protect us from potentially harmful substances. They’re trying to control our consciousness.

To get the public to lighten up on liberalizing drug laws, McKenna anticipated his stoned ape theory would cause a paradigm shift, to get voters and lawmakers to see psychedelics as inherently beneficial instead of as dangerous molecules. That get’s him an A for effort in our book.

Follow Randy Robinson on Twitter