Lead illustration by Lauren Genovese

This article was part of MERRY JANE's Jamaica Week 2017. We're resurfacing it today in honor of this year's Jamaican Independence Day, which is today!

When I was 22-years-old, I was sentenced to 25 years in prison for an LSD conspiracy charge. Despite being a non-violent offender with no past convictions, I served 21 years in total. That’s a long, long time, but I didn’t wallow in self-pity or spend my days carving lines on my cell wall. While I was locked up, I earned three college degrees, wrote for globally-recognized publications, and played a shit ton of soccer.

That might even be an understatement: I easily played on a dozen different teams in eight different federal prisons — over 500 matches throughout two decades in the belly of the beast. I wouldn’t say I was a superstar — no Lionel Messi by any means — but I was a good, fundamental player. I could run all day, had size and speed, a little technical ability, and, most importantly, a nose for goal. I wasn’t afraid to get “stuck in” or make a “hard tackle” — attributes that were highly valued in the rough-and-tumble affairs that served as games inside the big house.

"Soccer was part of my DNA, and the sport ultimately helped me adapt in prison. It gave me something to do that I had a passion for, and, dare I say, thrived at. Playing gave me truly positive feelings in an otherwise-negative environment."

Growing up in California, I was the type of kid who’d been playing soccer all my life — a veteran of AYSO leagues and select teams that I traveled with as a youngster. My mom was a “soccer mom” before they coined the term, and brands like Diadora and Patrick were my accessories of choice. The sport was part of my DNA, and soccer ultimately helped me adapt in prison. It gave me something to do that I had a passion for, and, dare I say, thrived at. Playing gave me truly positive feelings in an otherwise-negative environment.

The game itself was very different inside prison — not so much the rules or basic premises of the sport, which remained the same, but how it was played and who was actually playing it. Complaining wasn’t allowed, shin guards were for the weak, and serious injuries were treated only with ice, ibuprofen, marijuana, and hooch (if you could get your hands on them).

In prison, the games can be informal; sometimes featuring narrow goals with makeshift nets and no referees. Organized leagues exist though, and they come equipped with a commissioner, referees, coaches, and legit teams. The Recreation Department runs the leagues, and some compounds boast as few as four or as many as 30 teams in a single penitentiary. To be perfectly frank, the number of teams depended on how many prominent, certain nationalities were represented in a given Federal Correctional Institution (or FCI for short). In my experience, any compound with a large population of Colombians, Mexicans, or Jamaican inmates had tons of teams. In those instances, I’d literally be playing with former Colombian hitmen, Mexican cartel members, Peruvian coke dealers, Russian gangsters, as well as Jamaican Rastafarians who were often locked up for petty, nonviolent charges like me.

I was referred to as “el gringo” by pretty much all the other soccer players on the inside, though the nickname originally came from the Colombian athletes, who were by far the most talented soccer players in every single penitentiary I was held in. Once, I even pissed off a formerly infamous Colombian sicario at FCI Fairton in New Jersey. “I would have killed you on the street,” he told me in broken English after I had the audacity to complain about his reluctance to pass “el gringo” the ball during one game. Luckily we were playing with guards watching or otherwise I might have caught a shank.

In other words, it was a big change from playing out in the suburbs, though there were a couple white-collar criminals who occasionally got dirty on the prison fields, too. Every single one of these incarcerees took the game seriously — soccer is huge in prison. Rarely a day went by without a game going down, weather permitting. I remember almost all of them. But of all the crews I got on field with, the team that stood out the most was the all-Jamaican soccer team I played on at FCI Fort Dix, a low-to-medium security prison in New Jersey.

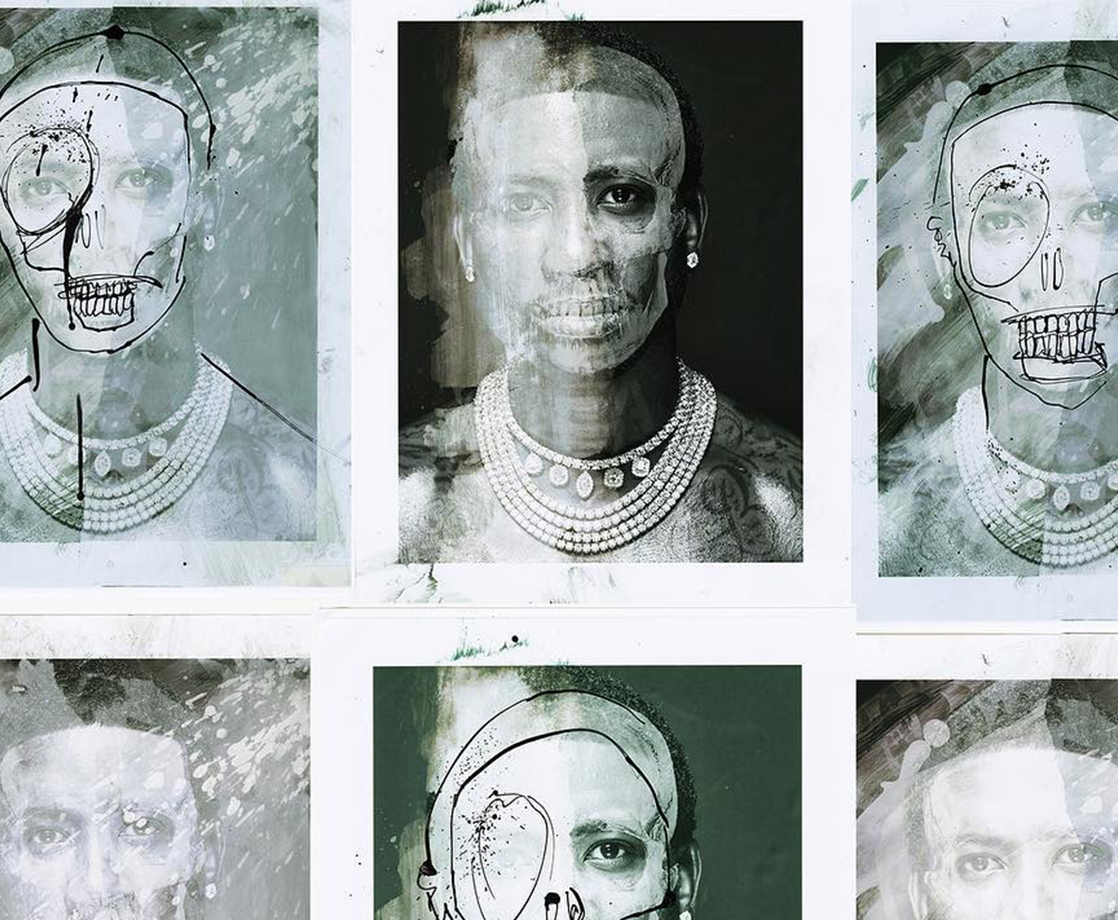

The author, pictured in the middle wearing Timbs, alongside some Jamaican inmates he was friends with while incarcerated. Photo courtesy of Seth Ferranti

Let’s backtrack a little bit, though. I got started playing soccer in prison at FCI Manchester in Kentucky around 1993, just as the season was about to begin. There, the sport was run pretty much like a college intramural league. We had four teams, mostly comprised of Mexican and Colombian inmates, as well as others originally from Central and South America. We played multiple times every weekend, but there were about 12 official games in a single season.The teams were organized by units, and my unit happened to include one of the best players on the compound, a Jamaican defender they called Checkly.

Prison is very racially oriented. As a white guy, I was expected to stick with the other white guys. But due to my interest in soccer, I found myself hanging out with Checkly and the other Jamaican guys on the compound. There were only about five Jamaicans in this penitentiary, since Manchester was a small institution with approximately 800 prisoners inside. Still, I developed a bond with them, a camaraderie built through the beautiful sport. My relationship with inmates from the island nation would even carry on to other federal institutions where I’d serve more of my quarter-century sentence. With an affinity for soccer, reggae, dancehall, and of course, marijuana, I had plenty in common with Checkly and the other Jamaican cats at Manchester. I was a stoner from way back, and so were they. It was natural to hang out with the Caribbean guys, kick the ball around, eat with them, and even smoke big spliffs when one of us had weed.

I played soccer for three years at FCI Manchester, even getting selected to an all-compound team that would play against college teams that visited the prison. I’d grown up mostly playing forward, but Checkly had me playing on the back line with him. My size, strength, and athleticism were perfect for defense. At 6-foot-1 and 185 pounds, I was a versatile player who could mark an opposing player out of the game, run down the flank and start the attack, or score goals with my head on set pieces.

"As an athlete and, more specifically, a soccer player, I wanted to prove myself in the best leagues I could. I had a lot of time to kill, and seeing myself improve at the sport was a way to measure and appreciate my self-growth while incarcerated."

In 1996 I was transferred to FCI Beckley, a brand new prison in West Virginia that opened up under Bill Clinton, who was turning the United States into incarceration nation. I was one of the first several hundred prisoners on the yard, and I helped set up the soccer league there. Acting as the de-facto commissioner, I tried to get all the Colombians, Mexicans, Jamaicans, and other soccer-playing foreigners organized into a league. During this time, I met Rupert, a technically-gifted Jamaican player, who’d just been transferred in from Fort Dix in New Jersey — about 500 miles away. He dazzled us with stories, claiming the penitentiary was the Bureau of Prison’s soccer mecca. All the best players and equipment were there, they had free-world teams coming from New York to play the compound’s best, and they played soccer pretty much every day, all year round. I’d heard the whispers before, but Rupert was the first to confirm to me in person that Fort Dix was the best place to play soccer in the entire US prison system.

By the late ‘90s, I was in my physical prime. As an athlete and, more specifically, a soccer player, I wanted to prove myself in the best leagues I could. I had a lot of time to kill, and seeing myself improve at the sport was a way to measure and appreciate my self-growth while incarcerated. But being in prison severely restricts your options in terms of where you can play, and with whom. FCI Beckley was too new, and the league too unorganized. FCI Fort Dix, the sports haven, never left my mind. It was a place where drugs and cellphones were supposedly prevalent, on top of being a holy place (relatively speaking) for inmates of the soccer persuasion. At this point, I’d been locked up for six years in two prisons, but I had an idea of how I could get moved to the prison of my choice. It was time to get transferred to Fort Dix.

In 1999, I applied for an educational transfer to the New Jersey prison, manipulating the system to serve my athletic interests. They had a woodworking vocational class I needed to pursue in order to find a career once I was eventually released — or at least that’s what I told the case manager who put the paperwork through and got my transfer approved. Soon, I was on my way to the most competitive soccer league in the prison system. It would either make me or break me as a soccer player. I thought I was A-League material — that’s what they called the best league in prison, though there was also B-League and sometimes even C-League — but the soccer community at Fort Dix would determine that.

When I got to the low security prison in the winter of 1999, my Jamaican friend Rupert hooked it up. He talked me up to his friends there and got me on the A-League Jamaican team, as some of their players had been deported back to the island and they were looking for replacements. There were a lot of Jamaicans at Fort Dix, due to its use as a purgatorial deportation spot for numerous immigrants who got arrested in nearby New York City. As a result, the penitentiary had all-Jamaican teams in the A, B, C, and over 35 leagues. When all the players would get together, there would be close to a hundred Jamaicans hanging out. I knew some Colombian guys there, too, but they didn’t ask me to play for them since I wasn’t good enough. Plus, none of those dudes were going to go out on a limb and vouch for “el gringo”; the Spanish-speakers saw me as an outsider. But it was a different story with the Jamaican players; they embraced me.

"I gained a sense of community and acceptance from the Jamaican guys. I felt like I had purpose in a place where finding that is few and far between. I never stopped being 'el gringo,' but they embraced me as one of their own."

The soccer season started in the summer of 2000, and I was ready to be the Jamaican team’s superstar playmaker and goalscorer. But maybe that was asking too much. I was new, they already had Jamaican players who were really good, and they weren’t going to give a top position to an unvetted newbie. The team, however, did need a defender — someone both big and fast. I was quickly deployed as the stopper in front of the sweeper in a diamond formation. Pretty soon into my tenure as a member of the A-League team, I was afforded a lot of respect and recognition throughout the prison — not dissimilar to being a varsity starter at a public high school. I hung out, chilled, and ate spicy Jamaican food every weekend with my teammates. Sometimes it would just be beans and rice, but if we scored from the kitchen we’d have chicken, green peppers, tomatoes, and onions. And if somebody smuggled out some flour, it was on — dumplings would be in every bowl, a Jamaican prison tradition. “You’re pretty good for an American,” an inmate who religiously watched us play told me halfway through the season.

I played with the Jamaican team for three seasons over the next three years. I had a good run, even scoring five goals one season. Not bad for a defender. I hung up my jersey — a real one, yet another perk of Fort Dix — when I was transferred back to a medium-security prison after I got in trouble for writing a critical article about the FCI system for Don Diva Magazine. But to this day, I still look back fondly on that time at Fort Dix, even though I was locked up. I gained a sense of community and acceptance from the Jamaican guys. I felt like I had purpose in a place where finding that is few and far between. I never stopped being “el gringo,” but they embraced me as one of their own. We were a good team, but we didn’t win the tournament — the Colombians did. We came close, though, losing to them by a penalty kick in the semi-finals. After that last game, me and Rupert enjoyed a smoke. It was a hell of a season.

Follow Seth Ferranti on Twitter