When Stephen Mandile was in high school, pot wasn't really his thing. He bought into the stigma that cannabis was for "hippies or druggies." Little did Mandile know that 20 years later he would be an Iraq War veteran fighting for the Veterans Administration to cover medical marijuana the way it does for addictive opioids.

Massachusetts resident Stephen Mandile was medivaced out of Iraq in 2005 with severe and painful injuries to his back (among other injuries). He was placed in a barrack at Fort Dix with other injured soldiers. According to Mandile, the atmosphere was bleak.

"There were guys that were on suicide watch that were popping pills all day, then drinking alcohol and gambling all night," he tells MERRY JANE. "There were quite a few suicides as well."

Mandile felt stuck at Fort Dix. He was told that it would be an 18 to 24 month wait before he could receive a medical evaluation through the military. He made it three months before asking for an honorable discharge.

He moved back home to Massachusetts where all his care transferred to the VA. The one constant that he received throughout his care was an abundance of pills to manage his situation.

He had yet to get a full medical evaluation, which caused his injured back to worsen during physical therapy. And even once he was fully evaluated, the pills continued.

"It was just, ‘What kind of medication do you want? Just call us every month and we’ll send it to you,’” says Mandile.

The pills, which ranged from pain medication to anti-seizure pills were subsidized by the government, and Mandile didn't need to pay anything out of pocket, even when the amount he took increased.

"At the highest point, it was between 35-40 different pills throughout the day," Mandile recalls. "I did it all: Methadone, Morphine, Oxycodone, Oxycontin, Percocet, Fentanyl… and that was just the opiates. I did tons of muscle relaxers and benzos, and more.”

Photo via Boston.com

Mandile was also taking medicine in hopes that the side effects of one medication would help the side effects of another.

"I was taking seizure medicine and I wasn’t having seizures!" he says. "I would go back to the VA and say, ‘Now I can’t feel my hands and for some reason everything I drink tastes like hot sauce.’ And they said it was just one of the side effects of that pill.’”

Mandile says that the VA would just increase his doses and encouraged him to give the pills more time to work, but his situation felt dire. Married and with two kids, he simply couldn't function on the schedule of pills they had him on.

"I pretty much wasn’t a parent, I was a zombie. I had so much anxiety and I would be in bed all day trying to wake up. If I was up at 8AM, I wouldn’t feel really awake until eight at night.”

And then things really hit rock bottom.

“It got to where I was online, looking up how high you would have to jump in order to die," Mandile admits. "I’d be looking at MapQuest and Google Maps, looking for a place where I could die away from everyone, where people couldn’t find my body and have to deal with the shame of my suicide.”

https://t.co/0fdPNQ3thP pic.twitter.com/NcGfX0NBHf

— Stephen Mandile (@sjmandile) July 7, 2016

It was at that point he realized there had to be something else that could help. Eventually, it was his wife that suggested medical cannabis after she read about it online.

“She doesn’t use cannabis or anything like that, ever," Mandile says, explaining that he never thought of marijuana as a real medical option. "But she saw that it was killing me… the pills ran my life. I didn’t leave the house anymore. I would count the pills all day to make sure I had enough for the night time.”

But getting a prescription for medical marijuana wasn’t that easy. When Mandile went to the VA to get a prescription, he was told that they couldn’t prescribe or fund medical cannabis because it was illegal on the federal level and they were a federal agency. Mandile’s own doctor at the Providence, Rhode Island VA tried to appeal to the higher ups, but nothing worked.

“I even had the doctor that is in charge of the mental health program and the pain psychiatry program at the Providence VA, he also tried to get the VA to prescribe medical marijuana and even he was turned down,” Mandile says.

He had to spend a couple hundred dollars of his own money to go to a doctor that specializes in medical cannabis prescriptions. Once he had a prescription and the state allowed the first dispensaries to open, Mandile began tapering off his pills. But he soon realized that he needed about two ounces of cannabis a week to get the same amount of pain relief he was getting with the pills, and that would cost him upwards of $800.

“I went from getting all my medicine at no charge to all of a sudden having to take care of myself with the money I earned through the VA,” explains Mandile. “But they don’t factor in health care costs.”

While Mandile struggled to afford his weekly cannabis costs, he was astounded at how he was better able to function on a daily basis than when he was on the opioids. The cannabis was non -addictive, and he never suffered any withdrawal symptoms – something he occasionally experienced with his Fentynal patch.

It was his experience with medical cannabis that got Mandile up in arms about providing better for Massachusetts veterans. He had witnessed so many fellow soldiers become addicted and ruin their lives due to the easily available (and free!) opioids. Now that he experienced the power of medical cannabis for himself, he felt that it was his duty to try and make it available to all vets in need.

“I want the state to find a way to put it under MassHealth, or I want them to allow my organization to be part of a system where veterans have a different place to go,” Mandile says, explaining his vision when it comes to veterans and marijuana. “That they don’t have to go to the VA, that they can have an alternative healing center where it’s more than just cannabis. We want to have acupuncture, everything that is considered alternative healing under one roof.”

And, if Mandile has his way, the connection between veterans and cannabis will go even further. He recognizes that the marijuana industry is thriving and that it can be a source of income and employment for veterans.

“I’m working with other people in the industry that wants to hire veterans and we want a place where we can teach veterans so they can go out and be part of the workforce in the cannabis industry.”

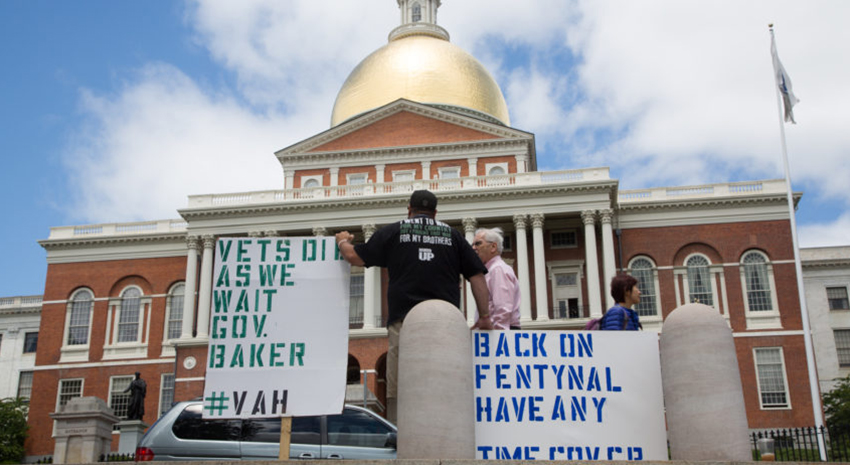

But none of this can happen if the federal government continues to keep medical cannabis illegal. And so, Mandile continues his fight. He shows up at the State House with his signs, hoping to get an appointment with Governor Charlie Baker. He tries to seek out representatives and legislators who will listen and support him. He implores them to look at the very real problem of opioid abuse in the state and at cannabis as a potential solution.

A visit to the State House last month encapsulated the uphill battle he is fighting. Mandile had gone to visit Senator Jason Lewis (Chairman of the Special Committee on Medical Marijuana) with the Massachusetts Patient Advocacy Alliance to discuss the legality of a particular amendment that would waive the Department of Public Health $50 card fee for veterans. When they arrived to give a copy to the Governor’s office, Mandile tried once again to schedule a face-to-face with Baker.

However, according to Mandile, office staff gave him the run around and refused to give their own names when he first asked. When Mandile took out his phone to record the event, staff called the State Police.

@SenWarren We are doing great things in MA for #Veterans w/ @SenJasonLewis pic.twitter.com/f6eiDhjBT2

— Stephen Mandile (@sjmandile) May 17, 2016

“I left feeling very confused and scorned and discriminated against,” Mandile emails to me a couple of days after. “I was sitting down in the corner of the room when the State Troopers were called on me. Was I being discriminated against because I am a Disabled Veteran? With PTSD, TBI, and a spinal cord injury? Or because I was a recovered Opiate addict? Or because I am a Cannabis patient?”

Mandile says he will never feel comfortable going to the State House again. He has moments of doubt if his work in Massachusetts is even worth it and wonders if he’s better off moving to accept offers he’s received in California or Colorado to help Veterans receive alternative treatment. But for Mandile who has lived in Massachusetts for 37 years and would love to see his daughters grow up there, it’s a hard choice to even consider.

“It’s a terrible feeling when you feel like your state sees you as a threat because you went and fought in a War, and want safe medicine over the death sentence on opiates.”

The last time we spoke, Mandile was back on the free-from-the-VA Fentanyl patch because he simply couldn't afford the amount of cannabis he needs each week to handle his pain and various injuries. But that’s not slowing him down. He continues to fight daily to ensure that veterans get the healing and opportunities they deserve.

Learn more about Stephen Mandile and his organization Veteran Alternative Healing Inc on his website and Facebook.