There's been a buzz around an old maraschino cherry factory in Brooklyn.

In 2015, Arthur Mondella, the third generation owner of Dell's Maraschino Cherries Company, took his own life in a bathroom at the large factory in Red Hook, Brooklyn's waterside industrial outpost. Before shooting himself with .357 Magnum pistol, Mondella had watched as police officers and environmental regulators were about to uncover a secret passageway to the factory's hidden basement, which housed a serious colony of cannabis plants and hundreds of pounds of pre-packaged bud.

At the time of Mondella's death and the grow-op discovery, the story straight out of Breaking Bad inspired national headlines and I-told-you-so rumors from dog walkers and postal carriers with strong senses of smell throughout the Brooklyn neighborhood. This week, however, a new deep dive into the subject from New Yorker writer Ian Frazier uncovers the full stranger-than-fiction story, including how Mondella's secret stash was discovered and how his daughters have taken the family business to new heights, sans-weed, in the years since.

Headlines from the original 2015 coverage of this strange tale

While most of the headlines about Mondella from three years ago focused on the cherry producer's unexpected suicide, Frazier's story begins all the way back in 2010, when bees in Redhook began returning to their hives glowing red. For a local beekeeping community that had just recently begun growing thanks to a change in local law, the site of bright red bees, and subsequently tinted honey, caused immediate concern.

But after ruling out all other possible explanations for the bees' color shift, local beekeepers tested the tainted honey and found food-safe red dyes; the exact same coloring used at Dell's Maraschino Cherries Company.

After helping to solve the sticky riddle, a local bee expert, Andrew Coté, met with Mondella to try and solve the problem. The two met amicably at the Dell's factory, where Coté offered advice on how to prevent syrup spills, tighten the factory's filtration screens, and generally keep the bees out of his product.

Fast forward a few years, though, and the highly-publicized red bees and their love for cherry syrup had drawn the attention of new Brooklyn District Attorney Kenneth Thompson, who had promised to clean up the industrial neighborhood, and began looking into open environmental infractions. The investigation into improper dumping and sewer usage, paired with longstanding neighborhood rumors about the smell of weed emanating from the cherry factory, led investigators from at least three different agencies, including the NYPD, to knock on the Dell's factory door that fateful 2015 day.

After Mondella saw police officers uncover a false wall in the factory, the cherry proprietor excused himself to the bathroom and shot himself with a handgun he kept holstered on his ankle.

"What a terrible situation," Red Hook beekeeper Tim O'Neal, who had been instrumental in solving the red honey dilemma, told the New Yorker. "He was a good neighbor. We all live in a community together — who cares if some dude is growing marijuana? It's practically legal now anyway. I'm sure he was putting out good product. I was shocked the situation turned out so badly."

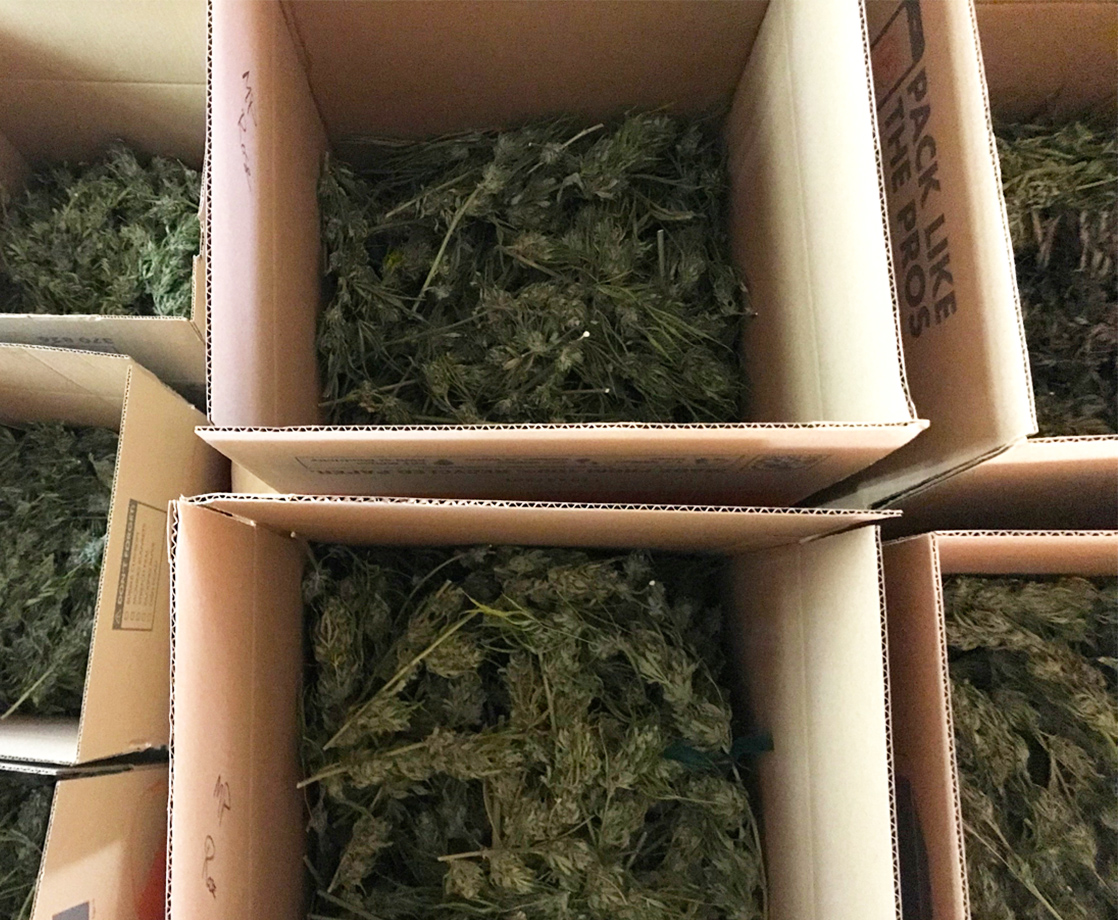

Once they had uncovered the hidden grow operation, police say the 2,500-square-foot, LED lighting-equipped space could have fit thousands of marijuana plants at a time, with hundreds of pounds of pre-packaged product suggesting that Mondella had done just that.

Since cannabis is outlawed in the Empire State outside of a still-nascent medical program, Mondella's underground operation was entirely illegal. But een with law enforcement closing in, it was shocking that the father, husband, and business owner would feel that being caught meant the end of his life.

As cannabis reform continues to sweep the country, Mondella's story is yet another example of the indirect dangers of cannabis criminalization. By the time the Red Hook indoor farm was discovered, legal marijuana sales had already begun in Colorado, offering a look at just how differently Mondella's life might have ended up if New York State were quicker to legalize or reform its drug policies.

After Mondella's death, investigators largely dropped their investigation into the expansive underground garden. Thompson charged the company with "criminal possession of marijuana in the first degree, a felony, and with failing to comply with laws relating to wastewater dumping, a misdemeanor," to which Dell's plead guilty on both charges, paid the requisite $1.2 million fine, and moved on with business.

In the wake of the unsuspected discovery and death at Dell's Maraschino Cherries Company, Mondella's daughters, Dana and Dominique, have taken over the family business, expanding the size and amount of cherries offered, streamlining new forms of production, and continuing their father's generosity and compassion towards the local neighborhood.

"The capacity that we're working at now, he would be so impressed," Dana told the New Yorker. "But I don't know if he would've been able to see that — not in his lifetime, because it wasn't in his nature to see it, to allow us to run with an idea, especially as it pertains to here. He was the type of person that did everything on his own."

The NYPD still hasn't arrested or charged anyone connected with Mondella's ganja grow, suggesting the Brooklyn cherry boss translated his autodidact attitude into all of his business endeavors, both sticky and sweet.

Follow Zach Harris on Twitter