When Golden State voters legalized an adult-use marijuana industry in late 2016, cheers rang out across the cannabis mecca of Northern California. In Oakland, though, city leaders immediately began constructing a social justice-focused program to make sure that longtime residents and people prosecuted for past pot crimes would have a leg up on the deep-pocketed tech bros and CEOs looking to carve out a slice of the green rush. Now, half a year into the West Coast's largest legal weed experiment yet, at least one Oakland ganjapreneur is calling foul on Oakland's attempt at equity.

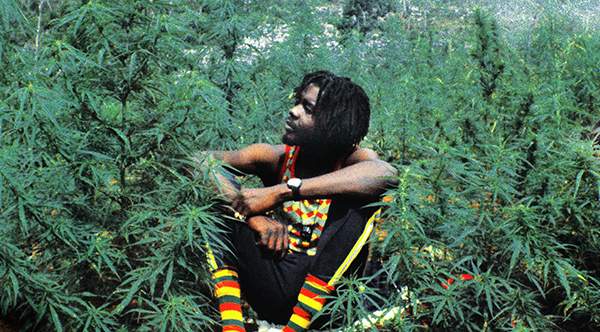

In a column for the San Francisco Chronicle, Otis Taylor told the story of Oakland-based cultivator and cannabis clone producer Alex Bronson. Through Oakland's local equity program, Bronson, a lifetime East Bay resident with more than 30 years of growing experience, said that he was able to bring his once-illicit business into full state compliance.

To help small-scale entrepreneurs like Bronson compete in a market flooded by outside capital and giant firms, Oakland's equity program allowed those larger businesses to skip to the front of the licensing line if they agreed to provide equity applicants with 1,000 square feet of business space, free of charge. Under a priority license "incubator" program, Bronson signed agreements with two larger cannabis companies, NUG and Joyous Recreation & Wellness Group, to give him a place to kickstart his clone sales operation.

But now, more than four months after Bronson expected to be growing compliant cannabis in an East Oakland warehouse, both NUG and Joyous have run into construction delays, leaving Bronson to run his business out of his small garage. According to the most recent timeline, Bronson will not have his promised space until November, a year after it was assured to him.

"The purpose of the equity program is that we're all starting off on a level playing field. That's why they got the priority license," Bronson told the Chronicle. "That's why they incubated us. And meanwhile, I'm sitting here with no income."

Challenging the apparent bait and switch equity assistance promises, Bronson has challenged both NUG and Joyous' local licenses, filing paperwork with the city to make sure they either follow through on their word in a more timely manner or shut down their own legal weed operations.

Upon hearing Bronson's accusations, the Oakland City Council immediately revoked Joyous Wellness' local authorization and called a hearing to hear the company's side of the story. After an immediate appeal, the company was granted an extension before another hearing convenes later this month.

"There's no enforcement of these agreements," Bronson's lawyer, Natalia Thurston, told the Chronicle. "There's no motivation for these people to follow through — unless the city does take action [to revoke permits]."

Before a separate hearing with attorneys from NUG scheduled for July 31st, a spokesman for that company's lawyers admitted a slow churn in securing Bronson's promised space, but placed blame on bureaucratic issues with Oakland's construction authorities, and not NUG itself.

"What's not to be expected is the city administrator's office would not acknowledge that this delay, if anything, is the building department's fault, not the general applicant's fault," Robert Selna, an attorney representing NUG, said. "The building department plays a significant role in the fact that Alexis Bronson doesn't have his greenhouse space."

If Bronson is made to wait until November before he can move his clone business into a larger space, as both NUG and Joyous Wellness are currently estimating, it may already be too late, with new licensing and upkeep fees due at the end of the year. After pouring thousands of dollars into turning his business legit and checking all of the boxes necessary for city-sponsored assistance, Bronson says that he is still waiting on the equity to arrive.

"Because I can't deliver a consistent experience," Bronson said to the Chronicle. "I don't have enough room to produce clones week in, week out to compete with my competitors. This is allowing my competitors to get a leg up on me."

Follow Zach Harris on Twitter