All images below courtesy of the publishers

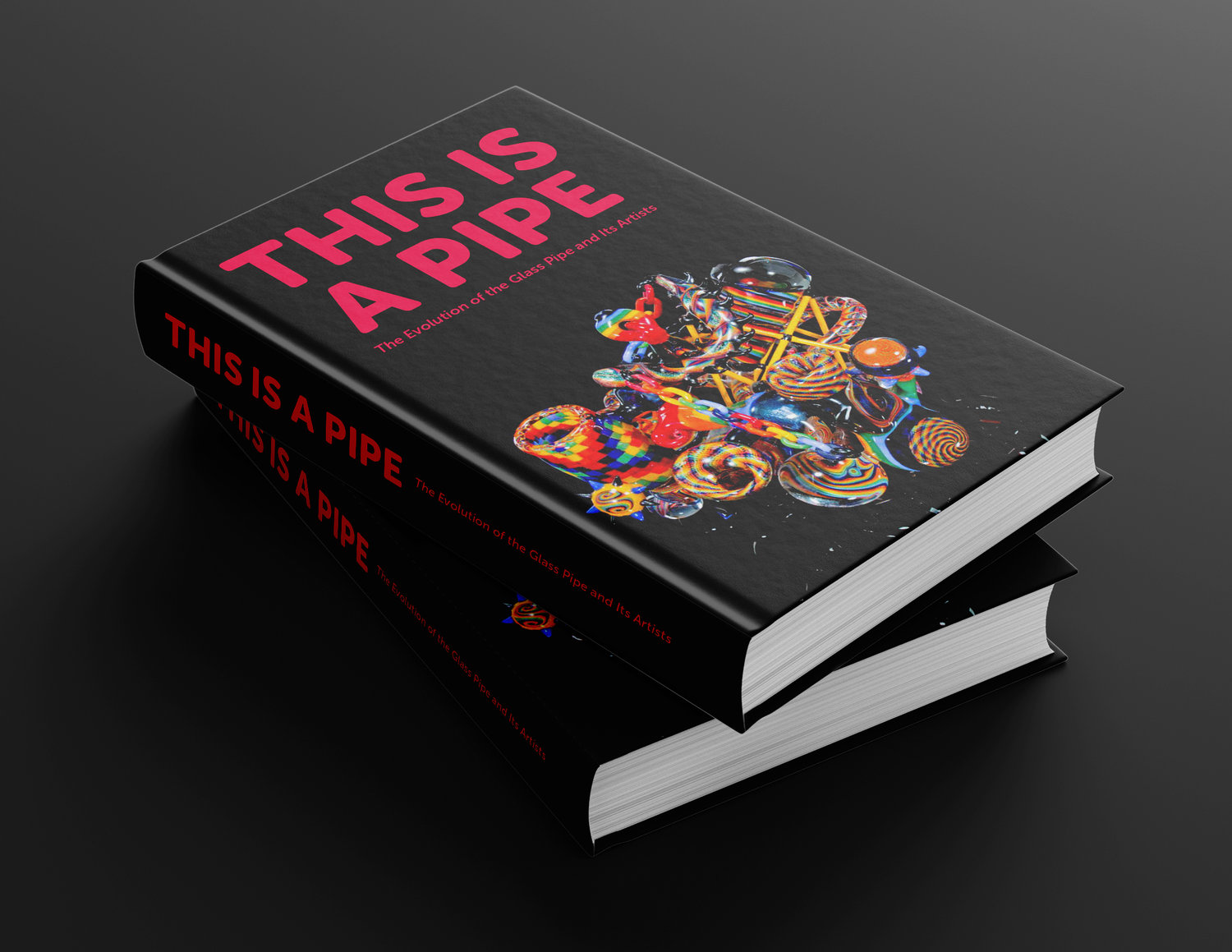

From the shelves of dankly-lit head shops to the pristine crevices of white-walled galleries, glass pipes are moving up in the world. In the newly released photobook, This Is a Pipe, authors Nicholas Fahey and Brad Melshenker offer an oral and visual history of expertly-designed bongs, bubblers, and chillums, presenting functional glass not only as objects to facilitate cannabis consumption, but as an emerging art form finding a new polish. The compilation is a testament to the American subculture, as well as its evolution from stigmatized “craft” to lucrative practice, to a medium worthy of the fine art canon.

A pair that perfectly melds marijuana culture and art world cred, Fahey is the second-generation owner of Los Angeles’ famed Fahey Klein Gallery, and Melshenker is the owner of 710 Labs, a California and Colorado-based cannabis concentrate company. Bringing their expertise together, with the help of writer Barry Bard, the duo tracked down 50 of the world’s most talented glass blowers, and collected stunning high-quality photographs of their most sought-after work, paired with engaging stories of the industry’s history, growing community, and game-changing technical advances.

To learn more about the art form of functional glass, as well as those bringing it to global esteem, MERRY JANE caught up with Nicholas and Brad on the phone from California, where we discussed Deadheads, federal raids, $160,000 pipes and why you’ll probably see dab rigs on display in museums sooner than you ever imagined.

MERRY JANE: Let’s start at the beginning. Nicholas, you come from the world of fine art, and Brad, you’re a veteran in many facets of the cannabis industry. How did you two connect and turn This Is A Pipe into a reality?

Brad Melshenker: We met at a gathering called the Pancake Epidemic in Los Angeles that a company called Street Virus used to host. They would throw these breakfasts on Friday mornings once a month where interesting creatives could come meet, hang out, and eat. I would go for the cannabis side of things and Nick was there for the art side, and we just started talking one day, and I happened to have a couple of my pipes there because they had a little dab room, and I was telling Nick what they trade for and who the artists are, and he was saying that it reminded him of when his dad got in the photography industry 35 years ago and people didn’t really respect it as an artform. He said “why don’t we make a book to document it?” and it clicked from there, and now two and half years later it’s finally here.

How difficult was it whittling the list down to 50 artists?

Brad Melshenker: That took a good three to six month. We met different artists who know the history and talked with them about who they felt should and shouldn’t be in it. We got feedback about how cliquey certain selections would be, knowing that they were artists that we liked that maybe others didn’t. Everyone has an opinion. It was hard.

Nicholas Fahey: Our Instagram has exploded in the days since the book was released, with people who haven’t even seen it asking, “Is artist x, y, and z in there?” and, “What about so-and-so?”

Brad Melshenker: But we had to cut it somewhere, so in the end the criteria that we came up with was every artist had to influence the industry in some fashion over the last 35-40 years, whether it be a cool technique or something that really made an impact, and you had to be making pipes still to this day. There are a lot of artists that had a lot of influence back in the day, but have stopped working on the torch or just didn’t evolve with the scene, and I felt like some of those people didn’t deserve as much recognition as the people that have showed consistency in the modern-day glass movement, which only started in the late 1990’s.

"Tetra, 2002" designed by Scott Deppe, photographed by Adam G

A lot of the glass blowers featured in This Is A Pipe were introduced to the craft in the parking lots of Grateful Dead and Phish shows. How much credit do jam bands deserve for the evolution of this culture on a whole?

Brad Melshenker: I think they played a major role for sure. Starting with the godfather Bob Snodgrass, who’s one of the biggest Jerry fans there is and toured around with them for years. I think he was the first one to really pick up the trade and, as he went on tour with the Dead, would pick up people that wanted to learn, and he was a very good educator willing to share his knowledge. So Snodgrass, through the Dead and Phish, really played a major role in at least the resurrection of it. Obviously, glass pipes go back hundreds if not thousands of years, but from the modern perspective that our book focuses on, parking lot culture was the beginning.

Nicholas Fahey: You could be from Philly and I could be from L.A., but if we’re on tour together, we’re homies and we’re having the same experiences. Through a lot of those relationships made on Dead and Phish tours, knowledge and skills were passed and people blowing glass across the country were able to connect. Spending all winter in a studio making pipes and then all summer on tour, they compared notes and were able to learn new things.

Similar to skateboarding, graffiti, and hip-hop, functional glass is still a relatively new subculture, where some of the greatest innovators and artists are just now entering their 30s or 40s. How has youth has played a part in the progression of pipe making?

Brad Melshenker: Functional glass is, to me, exactly like skateboarding or street art. And like jam band culture, a lot of the artists in the book come from a skating and graffiti background. Similar to those art forms, there’s less of an old guard telling you how to do things. With artists like Scott Deppe, who created the company Mothership Glass, people would see the work he was putting out in 2004 and say “Holy shit, how did he do that?” but that would only open the door for other artists to expand their own horizons and explore what was previously unthinkable.

"Redisculator #100, 2017" designed by Eusheen, photographed by Michael Zislis II

Like cannabis itself, the world of glass has had its own complications with law enforcement. Can you tell me about Operation Pipe Dreams?

Brad Melshenker: I always thought I knew about it, but going through the process of publishing This Is A Pipe helped me educate myself, too. Long story short, though, it put the industry back underground. In the early 2000s, glass shops were opening up all over the country, online head shops were popping up selling pipes, and the feds just didn’t like it. And so in 2003, cops raided Jerome Baker and a handful of the biggest glass shops in the U.S., and a lot of the artists went back into hiding, or back to tour parking lots, pulling their work from shops and online retailers. But somehow, [the culture] still found ways to thrive. One of the reasons we wanted to publish this book is to educate both new glass blowers and collectors about the foundation of this art and who you need to respect; who really sacrificed their lives for this industry.

In the years after Operation Pipe Dreams settled and the cannabis legalization movement began, what did the advent of dabs and the popularity of concentrates do to revitalize the functional glass scene?

Brad Melshenker: In 2009-2010 everyone went from making dry pipes to oil rigs and everything changed. With flower you can smoke it a bunch of ways, you can roll a joint, roll a blunt, you can pack a bong or a bowl, but hash consumption to this day is still a little harder. So glass blowers, being the most creative guys out there, started creating dab rigs. The oil movement, the hash movement — whatever you want to call it — really invigorated these artists’ creativity and desire to get back on the torch. They saw how much consumers were spending on hash, and frankly 90% of the glass blowers themselves love consuming concentrates, so it only made sense.

Nicholas Fahey: The motivation has always been, “How can we consume this product in the best possible way?” Going from the titanium nail to the quartz banger, and from glowing red to low temperature dabs, those are glass blower innovations. It’s not “This is how it is, we’re done.” No, every few months there’s brand new methods and products; these folks are the definition of aficionados.

Nicholas, you note in the book that functional glass, more than any other physical art form, has seen artists “freely sharing techniques, ideas, and even collections.” How has collaboration helped functional glass evolve as an art and as a culture?

Nicholas Fahey: The only other places I’ve seen artistic collaboration as it is in the world of functional glass is in theater or music. Two dimensional or sculptural arts is generally a solitary act. Looking at it from the fine art perspective that I have, we’ve done more than 360 shows at our family gallery, but I can’t think of one artist that would say “Oh yeah, sure, I’ll totally collaborate and give half of my money to another artist and introduce them to all my collectors and teach them all of this technical shit that I’ve figure out,” so that sharing culture is really amazing to me. It’s much more a renaissance-style where people are learning from each other and passing those skills down. Even the fact that it is simply accepted that glass artists split collaborative sales 50/50 is amazing. And it all comes from the cannabis community, where sharing is the name of the game. It’s the same concept as passing a joint.

"Dragonfly Utopia, 2013" designed by Darby Holms, photographed by Alex Reyna

How difficult has it been for the functional glass world to find acceptance in fine art communities?

Nicholas Fahey: I always think back to when my dad opened his gallery here in Los Angeles 30 years ago. 30 years ago, photography was not held in the esteem it is today. For example we’re having an Irving Penn exhibition at the gallery soon, and my dad was doing Irving Penn shows in the early ‘90s, where prints that are selling for $100,000 today were selling for $1,500 then.

And while the art world pooh-poohed photography as “not real art,” the market was eventually developed not within the art world, but by a passionate group of collectors who decided that prints were worth a certain amount. It wasn’t until that market was created that the rest of the art world decided “Oh, OK, maybe there is something there,” and I think that’s exactly what’s happening in the glass world, where artists are saying, “Fuck you traditional art world, we’re just gonna do this.” And now it’s interesting because even as those traditional art buyers are starting to sniff around for the money, the scene’s cannabis culture roots, the collaboration and comradery, are still strong.

You mention pieces that have sold for six figures to serious art collectors. Is it safe to say that high-priced functional glass is no longer exclusively of interest to well-to-do smokers?

Brad Melshenker: Just recently we saw a pipe go for $160,000, which I believe is a record in this small genre.

Nicholas Fahey: Several pieces have gotten into six figures at this point. And that speaks to the passion that these collectors now have for the work. It’s not just something for their coffee table or for their wall, people want to make this art a part of their identity and who they want to be.

Brad Melshenker: It’s growing, but it still hasn’t reached the heights that people expect it to get to.

Are there wealthy art collectors who display weed pipes in their house or gallery without even knowing its function?

Brad Melshenker: Specific artists like Buck and Jag disguise their work more thoroughly than others, but there are definitely art collectors out there that have a piece of glass in their house and have no idea its a pipe, for sure.

"Before Impact, 2010" designed by Buck, photographed by Scott Southern

The book itself is gorgeous. How important was it for you to present functional glass as a fine art?

Nicholas Fahey: That really was the whole point, to make it undeniable that this is fine art. Even when I was working in a head shop in 2002, I would have said it was art at that time, too. We’re just both in a position now where we can create the product that we knew we needed to have and that the community deserved. The book had to be great quality. It’s about taking cannabis culture outside of the stereotypes and showing people that this is a luxury industry and should be treated as such.

Where I’m based in Philadelphia, there seems to have been a revitalization of the head shop industry, where smoke shops are now set up more like art galleries and feature higher-priced pipes. Would you say that that trend has carried across the country?

Brad Melshenker: It’s interesting you mention that because Philly is definitely a glass hub, Denver is a hub, Seattle, Vermont, Austin, Texas, but yeah, that’s happening more and more across the country. But probably more important, outside of smoke shops, a lot of pipe makers have started doing their own shows, either at galleries or warehouses, where artists are making 10 or 20 pieces, and people will fly in from across the country because they’ve been waiting six months for a certain collection or collaboration to come out. That’s really taken off. The head shops are changing, but over the last 3 or 4 years the direct-to-consumer model has allowed artists to meet collectors and really humanize the process.

In that direct-to-consumer model, functional glass has recently found a new home on social media, where some well-known artists have amassed hundreds of thousands of followers. How has Instagram changed the glass game?

Brad Melshenker: I would say that social media accounts for 85-90% of all online sales in this industry right now. It’s a huge part of how this thing exploded and there’s no denying it. There are auctions in the comment section of Instagram posts every day. And like anything else, it’s opened access to a wider audience, in both good and bad ways.

Nicholas Fahey: It has definitely provided more educational opportunities. Back when I was working at a head shop in 2002, you basically had to take my word on everything. Not that I was lying, but there weren’t any Instagram or Facebook groups where you could check authenticity, and you definitely couldn’t just message an artist and have a conversation. I think that’s a huge reason the community has grown so much, because people are actually engaging with each other. If someone is selling bad glass or scamming, people will call them out and they’ll get taken to task.

"Light Seeker, 2012" designed by Laceface, photographed by the artist

Brad, you mention the negative aspects of that access, what do you mean by that?

Brad Melshenker: The transparency lets you see the good, the bad, and the ugly of the industry. I’ve seen numerous artists have mental breakdowns on Instagram — you can ruin your whole career with one drunken post, or an argument with another artist. One time, two artists got into a feud over commission for a collaboration and the one artist took a chainsaw and cut the piece in half; there’s a lot of drama. But outside of the personal issues, I know a lot of galleries have gotten upset because Instagram transactions take away from their role as a seller.

Nicholas Fahey: Being a gallery owner, that’s fascinated me. It’s not necessarily a bad thing, but unlike other art forms, it’s not developing this gallery support system. It will be really interesting to see how functional glass moves to the next level if there aren’t gallery directors who have institutional relationships where they can place these pieces at museums and get them into big auction houses, which is really the next step of this art form so that we can actually use those records to evaluate this stuff. Coming from the fine art world, if someone reaches out to me with a piece of art, I research past auction results to then create a value, and that influences insurance and more. But those same assertions can’t be made off of an Instagram auction.

As functional glass expands as a commodity and art form, do you worry that, like in cannabis, larger companies could eventually push out small operators and bring the still-underground culture into the mainstream?

Nicholas Fahey: I can see a way where that’s happening, but I also think they’re different markets. I see it all the time in the photography world. For example, there will always be people who want to go online and pay $100 for a pre-framed Getty images print of a flower, but there are also people who will walk into galleries and spend $150,000 on a picture of a flower that is made by a specific artist marked with a specific edition and signature. And in a way, functional glass needed to be elevated to that status to preserve it in that way. There will always be people making knock-offs, but there will still be status symbol pieces like there are in traditional art, and I have no doubt that serious collectors and museums will pull those pieces into their world.

"This Is A Pipe" is out now, order your copy here and follow the publishers on Instagram

Follow Zach Harris on Twitter