To donate to The Last Prisoners Project, visit their website here

“I have a life sentence, which is worse than a death sentence because with a death sentence you die once. With a life sentence, you die a little every day.”

These are the words of Michael Pelletier, who is serving a life sentence in a federal penitentiary for conspiracy to distribute marijuana. He started using cannabis medicinally when he was 15-years-old, four years after getting into an accident on his family’s farm and losing the use of his legs.

It wasn’t long after discovering the benefits of weed that he began traveling from his home state of Maine to get higher-quality herb just across the border in Canada. Once his friends realized what he was puffing on, they asked him to get more. Eventually, Pelletier caught the attention of law enforcement and was sentenced to life in prison.

Michael Pelletier courtesy of Last Prisoner Project

Despite the surge of legalization throughout the United States, approximately 40,000 people — including Pelletier, who has now spent half of his adult life in prison — are behind bars for non-violent cannabis offenses. That figure doesn’t sit well with cannabis activist and entrepreneur Steve DeAngelo, the co-founder of the pioneering Harborside dispensary in Oakland, California.

“I just can’t wake up in the morning and cash my paycheck from legal cannabis knowing that there are people who are locked up for doing exactly the same thing that I’m doing and not help them,” he told MERRY JANE in a phone interview. “That weighs on my personal conscience.”

DeAngelo and his brother and fellow businessman, Dean Raise, co-founded the Last Prisoner Project (LPP), a non-profit organization dedicated to ending incarceration for cannabis offenses and helping released offenders reintegrate into society. Achieving those goals, he says, is just an extension of cannabis legalization.

“We believe that the creation of a legal cannabis industry that’s generating intergenerational wealth creates a moral imperative to release the thousands to tens-of-thousands of people who are in prison for the exact same activity,” DeAngelo said.

A Friend’s Plight, the Impetus for Last Prisoner Project

DeAngelo was moved to create the Last Prisoner Project when a friend phoned him during negotiations for a legal transaction involving thousands of pounds of cannabis worth millions of dollars. His friend Chuck, who was serving a four-year sentence in a Pennsylvania prison for conspiracy to import 14 pounds of pot from California, was worried that his elderly mother had nobody to shovel the snow from her sidewalk after a snowstorm.

“All that Chuck has ever done his whole life is fix people’s cars for very reasonable prices, sing songs for free, and sell a little bit of weed,” DeAngelo insisted. “And he’s locked up for four years, and his mother is suffering, and he is suffering.”

DeAngelo explains that the Last Prisoner Project’s signature accomplishment thus far is a training program that prepares those recently released from prison to work in the legal cannabis industry. The program, known as the Prison to Prosperity Pipeline, is a partnership with Harvest Health and Recreation, a licensed cannabis company with operations in 18 states and territories.

“Eventually, we hope to be able to take that program actually into the prisons so that people can be learning how to participate in the industry and honing their job skills while they’re still incarcerated and make some productive use of whatever time is left there for them,” explained DeAngelo. “And then they get out of prison, and we set them up with a job in the legal industry.”

The Last Prisoner Project is also working on a clemency program that would streamline the process of releasing incarcerated people in legal states. By establishing a set criteria for this type of release, DeAngelo explains that governors would ultimately be freed of the political baggage that inherently coincides with releasing offenders from prison early. LPP is currently in the process of raising the $350,000 necessary to get the clemency program off the ground by spring 2020.

“We think we could get thousands of prisoners out, conceivably by the end of 2020, if we can raise this money,” DeAngelo said optimistically.

To support these fundraising efforts, the Last Prisoner Project is also partnering with licensed dispensaries to offer the “Roll It Up for Freedom” program, a campaign launching this spring that will allow customers to round-up to the next dollar on their purchase and donate the change to LPP.

“Buy from the retailers that are supporting our prisoners,” DeAngelo encouraged. “Buy from the retailers who are working to get our sisters and brothers back home to their families.”

Evelyn LaChappelle courtesy of Last Prisoner Project

Offering Assistance to Released Prisoners

Evelyn LaChappelle knows what it’s like to be separated from her family due to incarceration for a non-violent cannabis crime. She was sentenced to seven years in prison for conspiracy to distribute marijuana because she allowed her co-defendant, Corvain Cooper, to deposit the proceeds from cannabis sales into her bank account. LaChappelle was released in 2019 after serving five years and three months, earning early release by keeping her nose clean and completing a 400-hour life skills program. She told MERRY JANE in a phone interview what it’s like to be behind bars for activity that’s now legal in many places.

“I sat in the TV room in prison once watching Channel 7 news. And they’re highlighting women in the cannabis industry in Beverly Hills, and these women are telling stories about how it changed their lives, how they’re building wealth,” LaChappelle recalled. ”And there’s still 40,000 of us sitting in prison.”

After being released last year, LaChappelle didn’t believe that she needed assistance returning to society.

Evelyn LaChappelle and Steve DeAngelo courtesy of Last Prisoner Project

“I didn’t think re-entry would be a concern of mine. I have my degree. I have a pretty extensive resume before I was locked up,” she said.

She soon landed a job working at a hotel and thought she was on the road to putting her life back together. But when a co-worker searched LaChappelle’s name on the internet, learned of her past, and shared the information with her employer, she was fired after only six weeks on the job. After being referred to the Last Prisoner Project by Cooper, who is serving a life sentence in federal prison for his role in the conspiracy, LaChappelle sought out the group.

The Last Prisoner Project was able to help LaChappelle, offering to help pay her daughter’s elementary school tuition while she looked for a new job. She was soon speaking at LPP events, where she connected with Vertosa, a company that manufactures cannabis emulsions for licensed brands. She’s since been hired as a community engagement manager for the firm while continuing to stay active with LPP.

Sarah Gersten and Steve DeAngelo courtesy of Last Prisoner Project

Getting Involved

Sarah Gersten, the executive director and general counsel of the Last Prisoner Project, encourages members of the cannabis community to support the mission of the organization. In addition to donating, either directly or through the Roll It Up initiative, there are many ways to get involved, including volunteering for outreach efforts at popular events. Gersten also suggests that people share stories about how cannabis prohibition has personally affected them.

When Gersten was asked in a telephone interview when she thinks the Last Prisoner Project will achieve its goals, she expressed a positive outlook.

“I’m really hopeful that in the coming years we will certainly see a dramatic decrease in the US. But Steve DeAngelo, being the man that he is, had a really grand vision when he started that project,” she said. “And when he says he wants every last cannabis prisoner to be released, he means every last cannabis prisoner.”

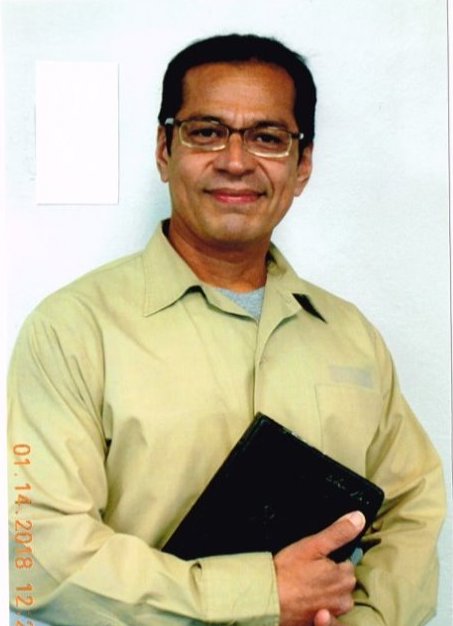

Edwin Rubis courtesy of Last Prisoner Project

That day can’t come soon enough for Edwin Rubis, a prisoner serving a 40-year sentence in federal prison for conspiracy to possess and distribute marijuana. He isn’t scheduled to be released until 2033, at which point he will have served 34 years behind bars. But he’s confident he’ll get out before then. He’s also grateful for the work of the Last Prisoner Project, on the behalf of him and others.

“It’s helping to re-humanize, just a little bit, those of us who have been dehumanized by injustice,” Rubis wrote in an email. “I love the LPP and everything they do for us. It really matters just to know that someone cares about what happened to me.”

You can support the Last Prisoner Project by donating online or by texting FREEDOM to 24365. You can also sign petitions asking President Trump to grant clemency to Michael Pelletier and Edwin Rubis at Change.org.