All photos courtesy of Kino Lorber

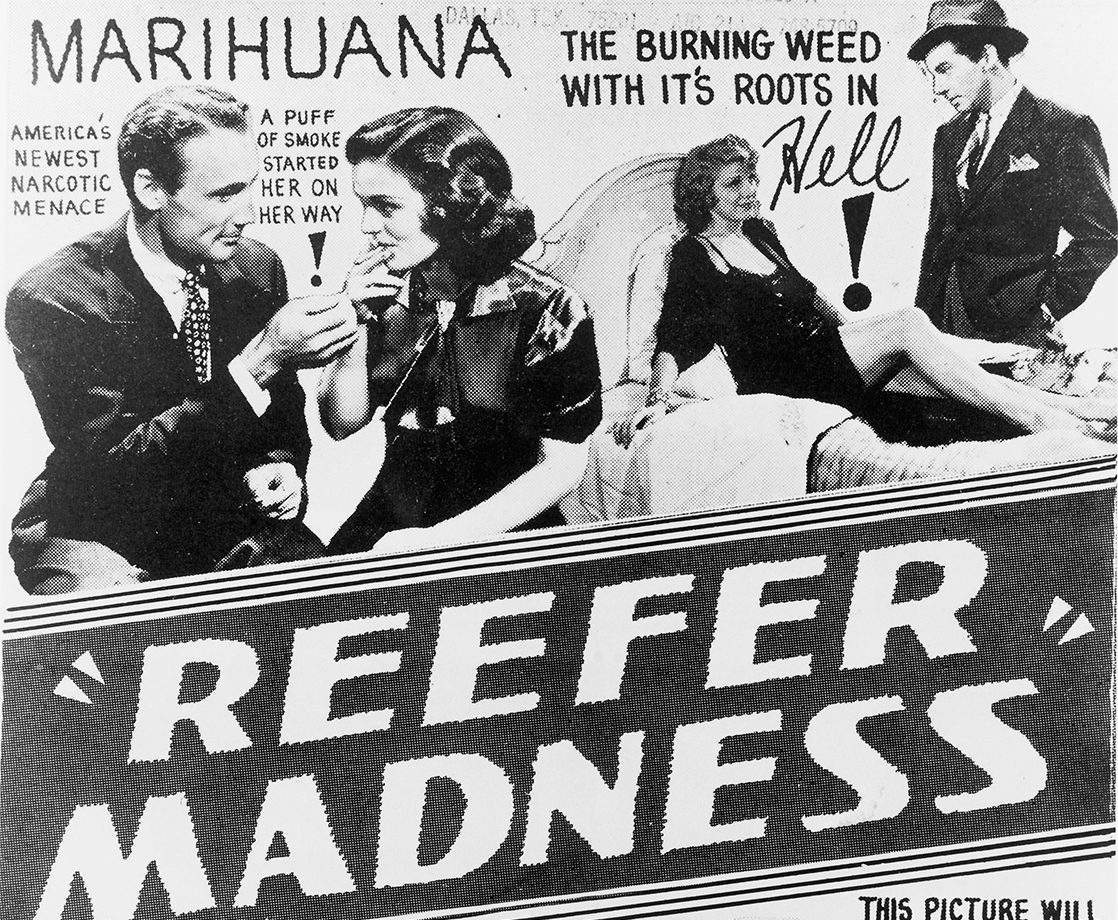

In the weird twilight world of anti-drug propaganda films, few can touch 1936’s Reefer Madness for its rabid misinformation and wrong-headed execution. Intended as a warning to parents about the dangers of marijuana, its story — about a pair of teenagers whose introduction to weed leads to addiction, insanity, and murder — is crudely executed, performed in near-hysterics, and so devoid of anything resembling rational behavior that it suggests that no actual humans were behind the camera. (The culprit was French director Louis J. Gasnier, a former specialist in silent comedy, whose career ended shortly after its release.)

Despite its kindergarten surrealism, Reefer Madness actually reflected the American government’s attitude toward marijuana at the time. Harry J. Anslinger, the head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, stoked public fears about marijuana through deceptive and decidedly racist stories about its ability to loosen the sanity and morals of users. He did this in order to sway public opinion against weed and to enact the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937, which levied fees for selling or prescribing cannabis. Support for the act from newspaper tycoons like William Randolph Hearst and films like Reefer Madness helped to push the bill into law, where it remained until its repeal in 1970.

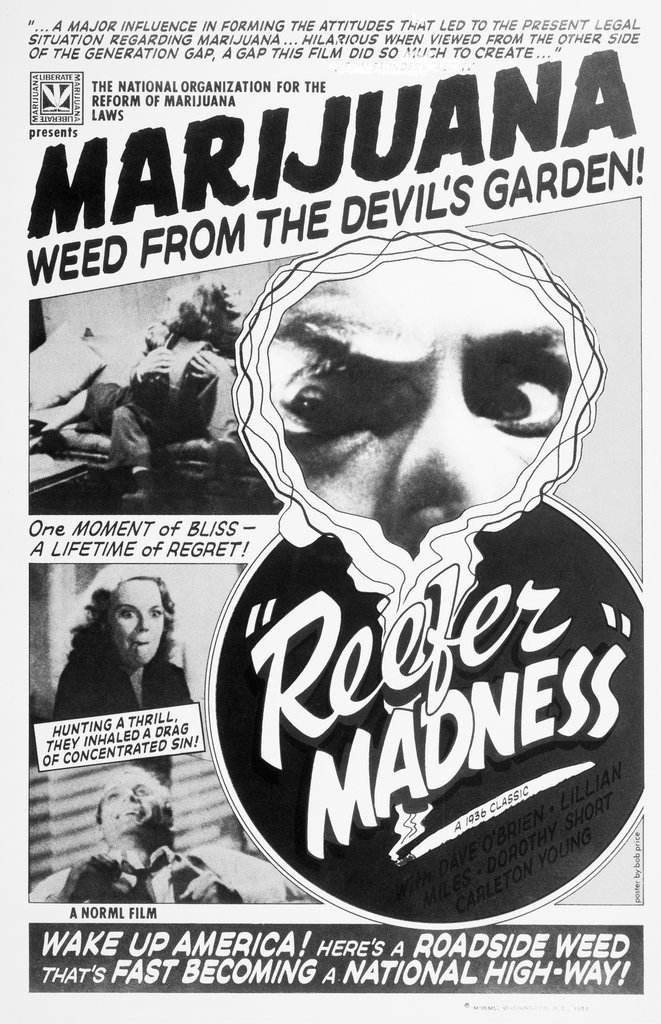

The people responsible for Reefer Madness may have faded into obscurity — Gasnier reportedly died broke, while the 1952 obituary for producer George Hirliman cites numerous low-budget productions, yet not Reefer Madness — but the film itself would enjoy a second act in the decades that followed, although as propaganda of an entirely different kind than its creators intended.

In 1972, Kenneth Stroup, director of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), discovered a print in the Library of Congress film archives. Hirliman had apparently forgotten to retain its copyright, allowing the film to lapse into the public domain. Stroup then screened it as part of a 1972 benefit. Audiences were floored by its incredible naivete about cannabis, and word of mouth made Reefer Madness not only a staple of the midnight movie circuit alongside The Rocky Horror Picture Show and El Topo, but also a new catch phrase for out-of-date and out-of-touch attitudes toward weed.

(Not everyone appears to have gotten the joke, as evidenced by author Alex Berenson, who employed the original title of Reefer Madness — Tell Your Children — for his fear-mongering anti-marijuana book).

Due to its public domain status, Reefer Madness has long been a staple of cheap home video releases, but a new Blu-ray from Kino Lorber — which partners the film with the equally out-to-lunch Sex Madness — offers what Lisa Petrucci of Something Weird Video (which teamed with Kino for its release as part of the new series “Forbidden Fruits: The Golden Age of the Exploitation Film“) calls the “best quality restoration [of the film] out there!” The Blu-ray also features commentary by Eric Schaefer, Ph.D, Professor of Visual and Media Arts at Emerson College, and author of “Bold! Daring! Shocking! True: A History of Exploitation Films, 1919-1959.” Dr. Schaefer spoke with MERRY JANE about the legacy of Reefer Madness, its cult appeal, and its convoluted history as both an anti-pot and pro-weed movie.

.jpg)

MERRY JANE: Reefer Madness is a textbook example of an exploitation film. For some, that term simply means “trashy” or “sleazy,” but as an exploitation film scholar, can you tell us what criteria defines an exploitation film?

Dr. Eric Schaefer: The term “exploitation film” originally referred to a movie that did not have big stars or fall into an easily recognizable genre and thus needed additional “exploitation” beyond the usual posters and advertising to find an audience. Such films included early documentary features, religious films, and movies that dealt with sensitive or sensational topics that often defied state or local censorship or the film industry’s efforts at self-regulation. By the time you get into the late 1920s and early 1930s, “exploitation” was most often applied to low-budget movies that were made by independents operating on the fringe of the mainstream industry and dealt with forbidden topics like sex hygiene, nudism, and drug use. When we get to the mid-1950s, the term came to encompass almost any cheaply-made film designed to make a quick buck.

When did you first encounter Reefer Madness?

I didn’t see it until well into the 1970s. But as a kid growing up in the suburbs during the 1960s, we were still being bombarded by educational movies that were straight out of the Reefer Madness playbook. And for me, the thought of trying marijuana was, Oh my God, I’ll go crazy… until I was at least in my twenties.

As you mention in the commentary track for the Blu-ray, Reefer Madness was one of three marijuana exploitation films traveling the country in roadshow presentations in the late ’30s, including Marihuana and Assassin of Youth. What made marijuana such an issue of concern — and a topic for exploitation — during the period?

Marijuana really burst into the public consciousness in the 1930s as a result of the efforts of Harry Anslinger, the head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics [which became today’s Drug Enforcement Administration]. Marijuana use was primarily associated with African-Americans and Mexican laborers, and Anslinger perpetuated the idea that its use was spreading to white, middle-class teens and would “degrade” them, making them unproductive.

Drug policy has historically been used in the United States to control minority groups, going back to the anti-opium policies used against the Chinese in the 19th century to crack cocaine policies used against black Americans in the 1980s. These programs have almost always been misguided and have had devastating unintended social and economic consequences.

Most of the anti-marijuana effort was rooted in racism and classism, and Anslinger spun stories about average kids becoming murderers or hopelessly insane under its influence. There was also the suggestion that cannabis broke down sexual inhibitions and could lead to mixed-race parties and unwanted pregnancies. Of course, by that time, any mention of drug use was forbidden in Hollywood movies by the Production Code. And since exploitation movies depended on the sensational and the taboo to bring in ticket-buyers, the campaign against marijuana made for a perfect match.

It’s safe to say that the film’s enduring popularity is due to its campiness, but what sets Reefer Madness apart from those two previously mentioned films and the others that followed?

The whole opening introduction, with the lecture by Dr. Carroll, is so pedantic and over-the-top, and that sets the tone for the rest of the movie. When it was issued on the midnight movie circuit in the 1970s, that was what set people off.

Is there any indication that audiences took it seriously?

It’s impossible to say whether all audience members in all places took the anti-pot films seriously. But no doubt many did, and the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and certain law enforcement agencies may have seen it as providing a useful anti-pot message. Sometimes you’d see a particular social organization or women’s club saying, “Yes, this is providing a public service.” But for every one of those, there were two or three others that said, “Oh my God, if you show people this stuff, they’ll be enticed into having sex or doing drugs.” They rode a rail between being seedy and having a message that was, at least at the time, somewhat educational.

But the movies reinforced all the information people were reading in newspapers and popular magazines, and they did so in a very vivid way. The only countervailing evidence at that time would have come from personal experience with marijuana. While the blame for the anti-marijuana hysteria can’t be solely pinned on Reefer Madness, it contributed to the campaign of propaganda against weed.

Let’s dispel a couple of myths about Reefer Madness. One is that the film was produced by a religious organization.

We can’t entirely rule out the proposition that a church or religious group put up funds for Reefer Madness, but I’ve never seen any solid evidence that would support the contention. First, we might expect some mention of sponsorship to be made in the credits, and there is none. Second, given what a bust [alcohol] prohibition had turned into — which had tremendous support from many Christian denominations — religious groups may have been a little wary of starting another crusade. If someone could show me evidence that Reefer Madness was backed by a religious group, I’d love to see it!

There are also references to producer Dwain Esper, who made some of the most lunatic exploitation films of the 1930s (Narcotic, Maniac), being responsible for the film’s distribution after its initial release. But that also seems to be misinformation about the film.

Esper already had his own anti-pot feature with Marihuana, which, based on newspaper advertising, may have gotten more screen time than Reefer Madness. He may have had the rights to Reefer Madness for a particular territory for a while, but he certainly did not produce the movie, which is sometimes suggested. Exploitation films were usually handled by multiple “states’ rights” distributors in different geographic areas over the years, and compiling any kind of comprehensive list for any given film is almost impossible.

Why was Reefer Madness such a hit on the midnight movie circuit?

As more and more people experimented with marijuana in the 1960s, they realized that its effects were not significantly different than having a few drinks or beers. (The potency of marijuana has certainly changed over the last 50 years.) When Reefer Madness returned to the screens in the early 1970s, it was met by an audience who had first-hand experience with it — unlike in the ‘30s and ‘40s. The “warnings” of Reefer Madness and the other pre-World War II anti-pot films seemed ludicrous and became the object of great derision. Dr. Carroll’s huffing and puffing about evils of marijuana, Ralph’s freak-out, and all the other scenes flew in the face of people’s lived experience and served as kind of a reverse object lesson.

Is the legacy of Reefer Madness that its execution helped, in a small way, people to see that marijuana policy of the past was problematic and ill-conceived?

By all means. The over-the-top nature of Reefer Madness and the other anti-marijuana films of the 1930s demonstrate just how much misinformation can create damage. Anything, from booze to bananas, can be used to excess and with bad outcomes. But the unconditional demonization of anything — as opposed to accurate information — can lead to policies that cause tremendous harm.

Reefer Madness, Marihuana, and Assassin of Youth — not to mention all press about marijuana in the 1930s — have been the source of a lot of laughs over the last 50 years. But they helped inform policy that was ill-conceived at best, pernicious and racist at worst. The United States might be in a much different — maybe better — place today if the movies and the distortions that they spread had never existed.

Though some people thought it was a bit jokey and over the top, even in the ’40s, its message was still pretty powerful in the 1960s and even the 1970s. Harry Anslinger and his minions did a pretty good job of demonizing the little plant, and even now, we haven’t seen a full 180-degree reversal on that attitude. There’s still a lot of fear about it, and a lot of it goes back to the idea that if you start using it, you’re going down the path to perdition. Even Joe Biden was talking recently about pot as a gateway drug to heroin and other things. Old tales die hard.

For more on Dr. Eric Schaefer, visit his page on Emerson’s website here

To order a copy of the “Reefer Madness” reissue, visit Kino Lorber’s website here