If I told you the story of Santa Claus and his airborne herd of hoofed accomplices can be explained by hallucinogenic fungi, would you believe me? What if Santa were actually kinda real, in that people used to hallucinate his existence? That’s right. The same psychedelic mushrooms found to treat extreme bouts of anxiety, alleviate symptoms of depression and make one dance non-stop til the breaka-breaka dawn at Bonnaroo could explain the Christmas myth we’ve all come to know and love.

What Is Amanita Muscaria?

Amanita muscaria, also known as fly amanita or fly agaric, is a hallucinogenic mushroom widely used in both recreational and spiritual practices, with ancestral origins among many of the indigenous inhabitants of Siberia. An archeological image found on a cave in Tassili, Algeria, dating back to 3500 BC details mushrooms with animated auras surrounding dancing shamans.

While these mind-altering fungi are classified as poisonous, very few human deaths have ever been reported from their consumption. A technique called parboiling is often used to break down the mushroom’s psychoactive properties and weaken toxic chemicals, allowing it to be ingested with fewer negative side effects. Native to temperate and boreal regions of the Northern Hemisphere, you’ll find them camped out beneath various species of coniferous and deciduous trees. With impressive white spots against bright red bulbs, the mushroom has become a popular icon in many cultures across the world.

You’re Just Tripping

“Reindeers flying—are they flying, or are your senses telling you they’re flying because you’re hallucinating?” Harvard biologist Donald Pfister asks a library full of university students and faculty, during his annual Christmas Eve lecture on the link between Santa and Amanita muscaria. Every year, Santa takes a “trip” around the globe. According to Pfister, both reindeer and people consume the “holy fungi,” which may start to explain a few things here.

Santa the Shaman

John Rush, Ph.D., author of Mushrooms in Christian Art and professor of anthropology at Sierra College in Rocklin, Calif., suggests, “Santa is a modern counterpart of a shaman, who consumed mind-altering plants and fungi to commune with the spirit world.” He believes the Santa myth was born because local shamans in the Siberian and Arctic regions would visit locals on the winter solstice, an astronomical phenomenon strongly related to modern-day Christmas, with gifts of dried hallucinogenic mushrooms.

“Because snow [in Siberia] is usually blocking doors, there was an opening in the roof through which people entered and exited, thus the chimney story,” he says. Plus, Siberian shamans donned red deer pelt garb meant to emulate the Amanita mushrooms’ red bulbs, and reindeer served as the shaman’s “spirit animals.” Carl Ruck, a professor of classics at Boston University adds, “Amongst the Siberian shamans, you have an animal spirit you can journey with in your vision quest.”

Mushrooms and Christmas Iconography

Considered to be a symbol of good luck, the fly agaric has popped up on Christmas cards around central Europe for quite some time. In southern Yugoslavia, folklore spins a tale of the Germanic god Wotan, who rides his steed through the forest on Christmas night, chased by devils as red and white drops of foam and blood spray from the horse’s mouth. Where the blood touches the ground, fly agarics grow the following the year.

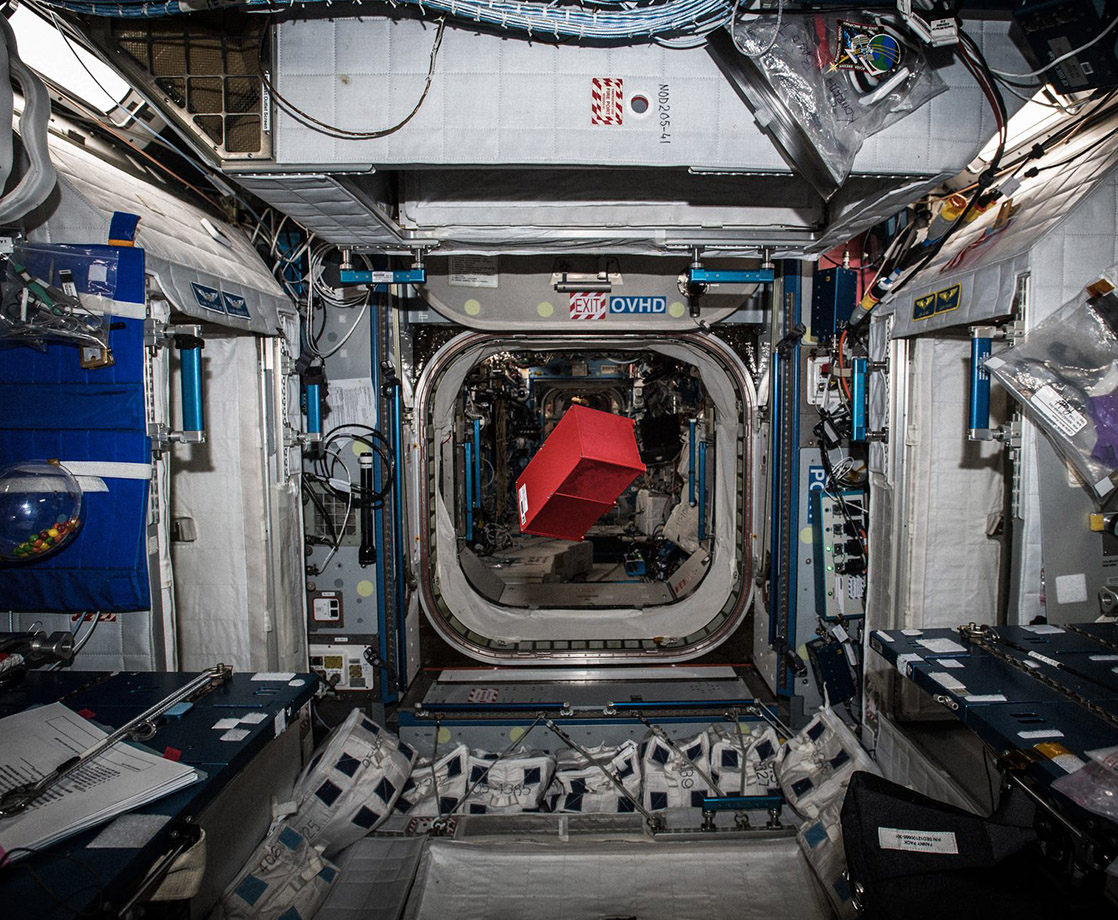

These consciousness-expanding toadstools sprout up beneath conifers and birch trees like enticing little Yuletide treats. The symbiotic relationship between these mushrooms and trees may explain why there’s so much related imagery found in Christmas iconography—ornaments, Santa’s traditional suit, and even Rudolph’s red nose. “It’s amazing that a reindeer with a red-mushroom nose is at the head, leading the others,” asserts Professor Ruck.

What Naysayers Say

Ronald Hutton, an historian and professor at the University of Bristol, insists the connection between magic mushrooms and Santa Claus is erroneous. “If you look at the evidence of Siberian shamanism, which I’ve done, you find that shamans didn’t travel by sleigh, didn’t usually deal with reindeer spirits, very rarely took the mushrooms to get trances, didn’t have red-and-white clothes,” says Hutton.

Meanwhile, scholars argue that Hutton’s perspective is too literal and he fails to recognize flying reindeer with sleigh bells ringing are symbolic of a celestial journey, a hallucinogenic experience.

Yet Hutton’s beliefs point to something interesting: Santa, as we know him today, is a far cry from a wizard-like shaman coaxing mystical trips out of the populace. Comparatively, he’s pretty straight-laced. Modern-day theatre and literature have painted a more Rockwellian portrait of the jolly-good-fellow.

“The Santa Claus we know and love was invented by a New Yorker, it really is true," says Hutton, referring to the famous poem “The Night Before Christmas.” “It was the work of Clement Clarke Moore, in New York City in 1822, who suddenly turned a medieval saint into a flying, reindeer-driving spirit of the Northern midwinter,” he claims.

Certainly, Moore’s poetry helped define our modernist Saint Nick. And while no one’s quite sure what inspired his vision, both professors, Rush and Ruck, believe the poet borrowed motifs from northern Europe that were influenced by Arctic and Siberian tradition.