All photos courtesy of FUEL Publishing

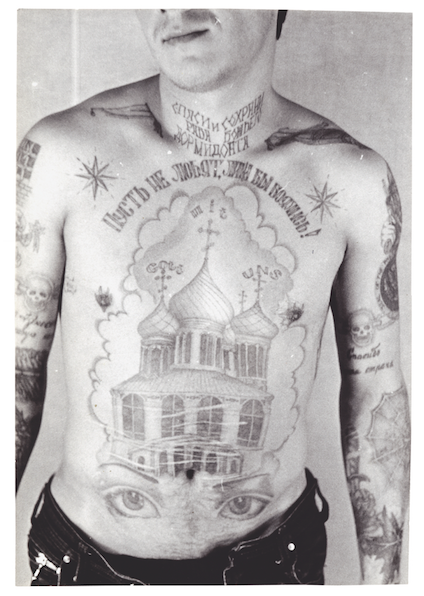

In the new book Russian Criminal Tattoos and Playing Cards, FUEL Publishing provides a fascinating and visually-stunning guide into a graphic underworld filled with secret communication, lurid semiotics, and DIY body modification.

The new volume expands on FUEL’s previous releases under the Russian Criminal Tattoo Archive umbrella, a collection that includes over 3,000 illustrations made by a former prison guard, and photographs complied by a former KGB officer.

As the new project’s title implies, the focus here is on playing cards. While gambling was restricted by prisons, that didn’t stop anybody, as “the respect commanded by any criminal was directly related to his ability to win at cards.” The authors explain that “failure to pay a gambling debt could result in a forcibly applied tattoo, lowering the bearer’s status. Fingers, ears, even eyes, might be lost — cut off in the presence of other prisoners as witnesses.”

The book incorporates 150 previously-unpublished photos, accompanied by insider details about how the gambling ephemera was created, the hidden messages behind certain imagery on the decks, and why card culture is intrinsically linked to specific criminal behavior and specific tattoo designs. Damon Murray, the mastermind behind FUEL, took some time to talk to MERRY JANE about Russian Criminal Tattoos and Playing Cards. Deal yourself into our conversation below.

MERRY JANE: Tell us a bit about the Russian Criminal Tattoo Archive — can you explain what it is for the unfamiliar? How did FUEL come to be involved with it?

Damon Murray: The Archive developed organically from our work with Russian criminal tattoos and the main artists that documented them in the former USSR. We published our first book on the subject, The Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopaedia, in 2004, just before the author and creator of the amazing drawings, Danzig Baldaev, died.

Following his death, we worked closely with his widow to produce the second and third volume of the Encyclopaedia series. During this time, she asked us if we would like to purchase the entire collection of his drawings, which were stuffed into their cramped St. Petersburg apartment. This initial collection formed the basis of the archive. To this, we’ve added the photographs of Sergei Vasiliev and Arkady Bronnikov. Alongside the books we’ve published explaining this material, they form the largest archive on this subject.

What led up to the playing card project, specifically?

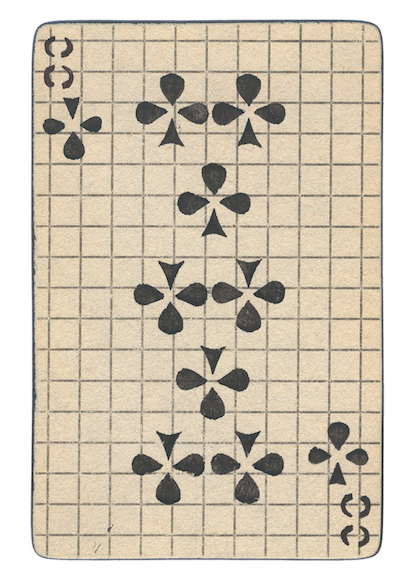

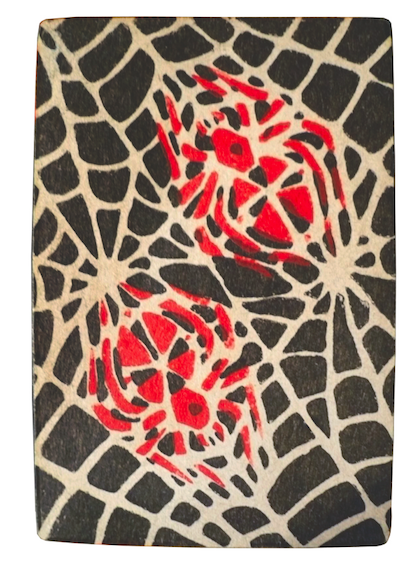

We had come across several packs of prison playing cards during our travels in Russia. The differences between the packs were fascinating — their opaque designs seemed to serve the opposite purpose of standard cards: they intended to confuse rather than inform.

Investigating further, we learned of the importance of playing cards in the Russian criminal world. No reference books existed on this topic, and where it was mentioned (largely in academic texts) there were few, if any, images.

We thought that a book fully explaining the link between cards, tattoos, and the Soviet prison hierarchy would be of interest to tattoo enthusiasts, as well as graphic designers and academics.

Both tattoos and playing cards are essential elements of outlaw culture. In a larger sense, what do you think connects them?

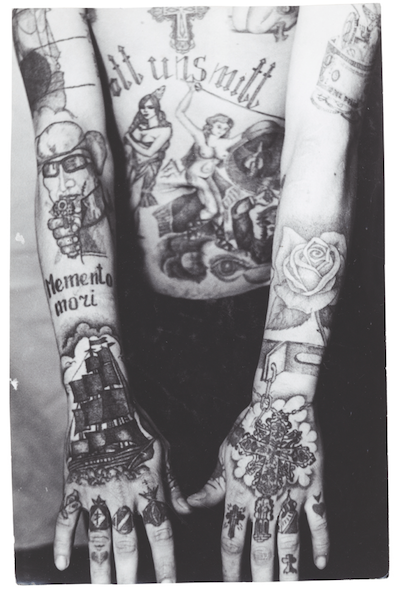

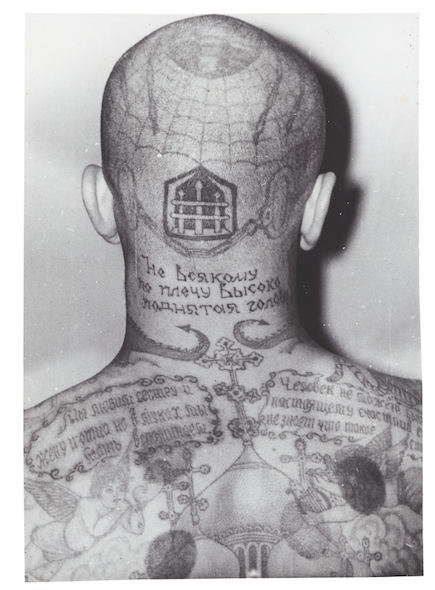

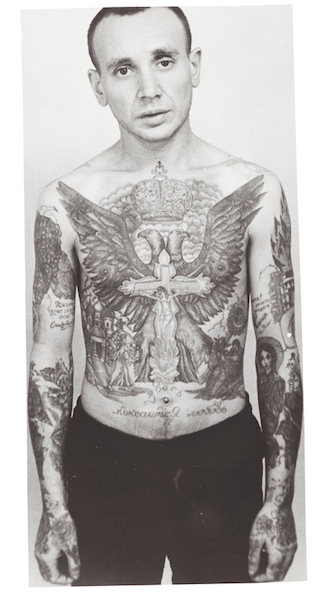

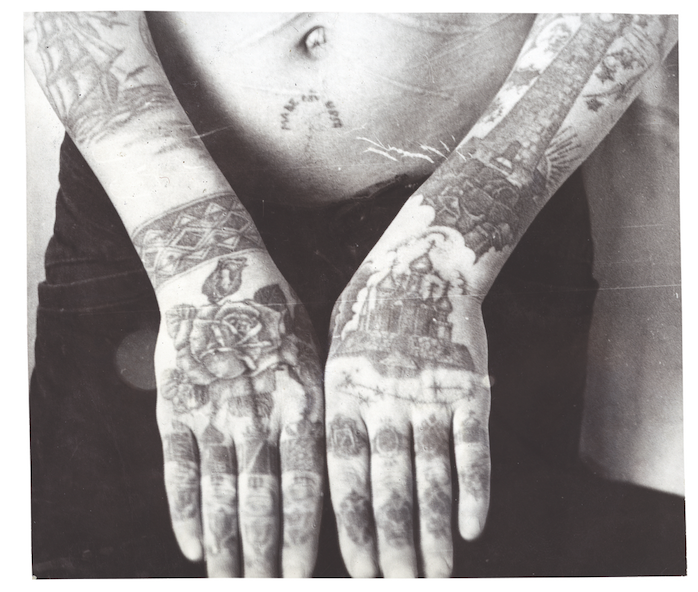

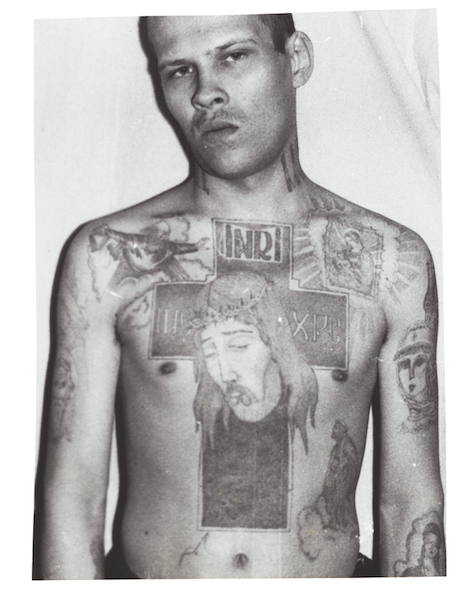

In broad terms they, represent an attitude of risk. Originally, tattoos carried a stigma — the first Russian criminal tattoos developed from the word VOR (thief) that was branded directly onto the criminal’s face.

These can be considered the earliest symbols of membership in the world of outcasts: the first criminal tattoos. Though forcibly applied, they nevertheless began to function as caste markings. For the bearer, there was no way back. These criminals cultivated a nonchalant attitude towards their own lives. Their tattoos developed into a coded system that acted as a visual CV, displaying their successes, failures, even sexual proclivities.

In the criminal world, the act of playing of cards has a similar function: it is a performance — a display of eagerness to take risk and cheat a system. Playing cards shows the gambler is living the fast life of a criminal, with no consideration of the consequences.

A Soviet-era thief was expected to carry a deck of cards at all times. He had to be ready to play anywhere, under any circumstances, even when going about his profession. When incarcerated, card playing relieved the monotony of the “zone” (prison or labor camp). Outside, criminals are accustomed to constant tension; inside, card games give him the necessary, physiological perception of risk.

What is specifically Russian about the artwork of these tattoos and cards?

Uniquely, the language of playing cards was used to convey the status of a prisoner. This worked across all levels of prison hierarchy. Danzig Baldaev (Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopaedia Vols I-III) refers to the existence of various masti (suits) within the “zone,” such as the mast muzhikov (the suit of men), mast blatnykh (the suit of criminals) and mast kozlov (the suit of jackasses).

Here, a “suit” can signify a section of the prison or camp community who are not thieves in the narrow sense, but are united by a particular trait (the suit of jackasses), or a category of individuals who have ended up in prison but do not belong to the community of thieves (the suit of men). However, they all form part of the same social system.

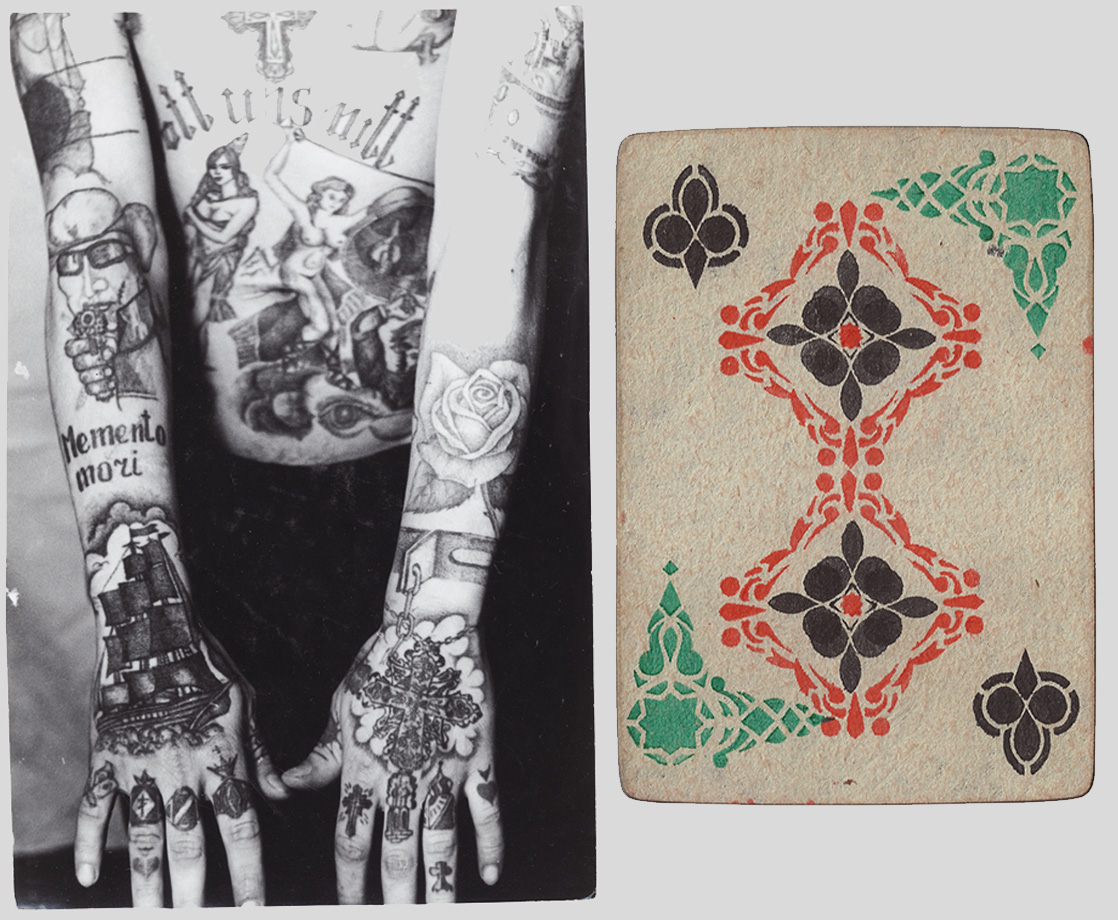

Tattoos were an essential part of this system, with playing card references reflecting prisoners rank: the black suits of clubs or spades acted as symbols of “legitimate thieves,” while the red suits of hearts or diamonds “lowered” the bearer’s status within the “zone.”

Can you tell us a bit about the specific castes within the system?

The symbol of hearts transforms the bearer into an erotic object, denoting that he plays the role of a “woman.”

The symbol of diamonds is forcibly applied to informers to warn other inmates. Some informers might be subject to violent retribution. To prevent betrayal by an individual cellmate, the whole cell would participate in the murder of the informer, making everyone culpable.

Shesterkas — literally ‘sixers’ — were named after the lowest card in a standard Russian 36-card deck; a seven is the lowest card in a standard 32-card prison deck. “Sixers” served as underlings, and every “self-respecting” criminal would have one or two, while a high-ranking “authority” might have ten or more. They were marked by their own ring tattoos — either the number 6 or dice-like dots. Their work included cleaning clothes, footcloths, and shoes, distributing messages to other inmates, writing letters, bringing food from the canteen, preparing chifir (a strong, narcotic-like tea), keeping lookout during card games, reporting on the psychological climate in the prison, and providing passive homosexuals.

“Erotic” images of copulation were forcibly tattooed onto those who lost at cards but were unable to pay their debts. In this context, such tattoos are devoid of any sexual meaning; instead, this punishment deprives the person concerned of any status in the world of thieves.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the book deals with how the cards were actually constructed by prisoners. Can you tell us a bit about that?

In the same way that tattoos were made by cannibalizing ordinary articles to make machines, ink, etc., cards were constructed from scratch using innocuous materials procured from the everyday routine of prison life. Below is a simplified version of this complicated and skilled manufacturing process, which is described in much greater detail in the book.

Two sheets of paper were glued together: the rubashka (literally, “shirt”), was the back of the card and was made from a thin notebook cover, while the pitshatka (literally, “writing”), was the face and was made using a page from a book or writing paper. Adhesive was made from chewing prison bread, which was then passed through linen. Bread was a basic building material for prisoners and could even be shaped into ‘shanks’ used to stab other inmates. These were then broken down in hot water, dissolving the evidence.

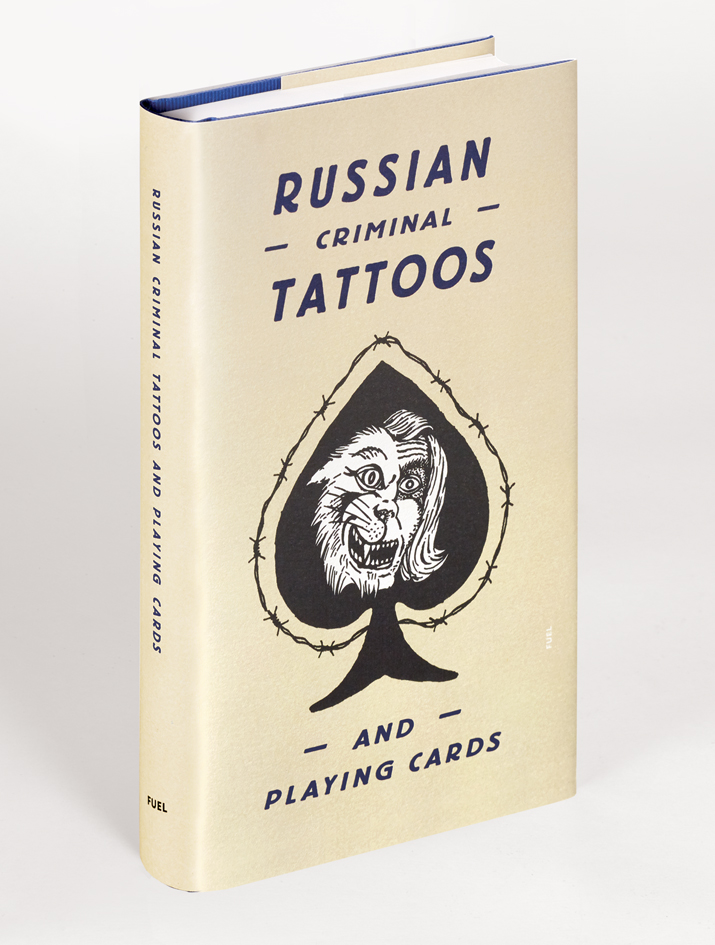

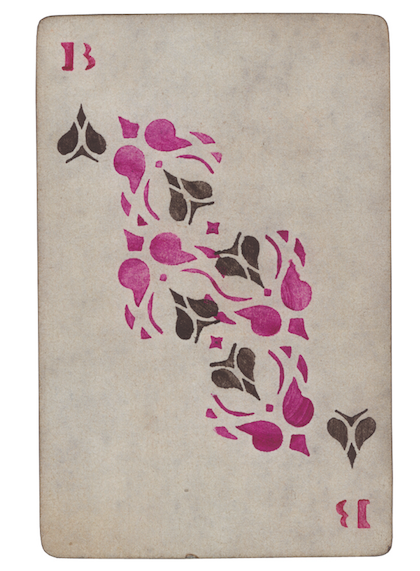

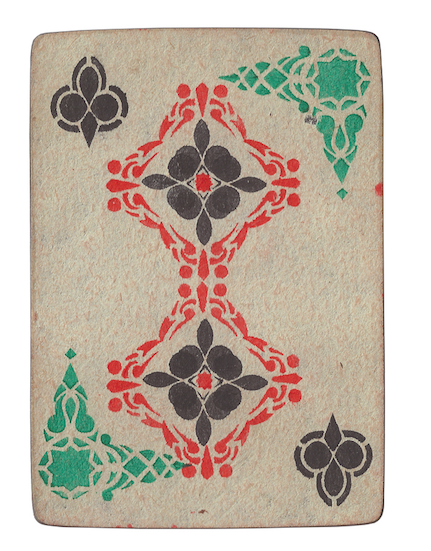

After the cards were pressed, they could be cut to size, fitting neatly into the palm of the hand, making them easier to handle, cheat with, and hide. A prison deck consists of thirty-two cards, the lowest being a seven. The development of designs for the face was inextricably linked to the history and psychology of playing cards in prison. While normal cards have a distinct suit, with pictures and numerals that are easy to read, prison cards set out deliberately to confuse. The use of similar colors and patterns made it difficult to distinguish between cards, distracting attention from the game itself.

Different regions and prisons had their own favored pitshatki. The choice of design also depended on a player’s nationality and culture, making card production a form of traditional artistic practice. Decks might be smuggled into prison, but generally they were made specifically for each player so the marks could be specified to suit the player’s game.

The “paint” for the markings was prepared from soot (for the black) and blood mixed with bread glue (for the red). Another parallel can be drawn here between tattooing and cards, where the ‘ink’ for tattoos was mixed from the bearer’s own urine and soot. If available, flecks of lead from colored pencils might be used, but experienced players preferred blood as it dried darker, making the cards more difficult to read, especially in low light.

Stencils were cut from the silver paper of cigarette or tea packets, and the paint was then dabbed through the stencil onto the card. During this process, the design was manipulated to assist in cheating. In games where face-down cards were lifted from the deck, the position of the design could be felt by the player who knew the deck, allowing the player to recognize the card without turning it over (textured paint also served the same purpose).

Both the sharpening cards and the production of the rubashka — the pattern on the back of the cards — offered opportunities for the application of concealed markings. The intentional miss-registration of the pattern was used to denote a card’s value; even the direction of the paint (applied with a home-made brush) was used as a means of marking.

Once the rubashka dried, the cards were sharpened. The packs would be fanned out so two edges could be planed using a long piece of broken glass, shaping them into a cone. Then, the opposite two edges were planed, followed by the corners. The deck was then turned upside down and the same process was applied to the reverse. The cards were then shuffled and the procedure would be repeated until all the edges were the same, however they were turned.

Sharpening removes around 1 millimeter from the edges and between 1.5 and 2 millimeters from the corners, providing a new paintable area. The card was no longer quite rectangular and all the edges were shaped into a cone. Marks made on these sharpened edges were usually applied to picture cards, and were important in games where the opponent’s hand remains visible. Although these marks were the most difficult to make, they were also the hardest to detect. Finally, the cards would be ready. The search for a “goose” — an inexperienced beginner who would agree to play — could begin.

Put simply: how did the cards “work”? What kind of games did users play with them? What were the stakes?

Games such as Terz, Stoss (a version of Faro), and Bura were played, each having various interpretations of its rules, depending on the region of the prison and the individual players. Games such as Twenty-One, which involved multiple players, were avoided by the kartoshnik (card sharp). He favored games involving only one other player, as this allowed them greater control and more opportunities to cheat.

Cheating was viewed as a skill, admired by the thieves as part of the game. A good player could not only manipulate the deck by reading marked cards but also talk their way out of a dubious loss.

Stakes varied. Having lost all his money, food, and cigarettes, a thief might move on to parts of his body. Poimet vetochku (to get a twig) is where the stake is a finger or toe (usually the little finger or toe, depending on their agreement before the game), in the presence of other prisoners as witnesses.

Poimet pelmen (to get a dumpling) is to win an ear, or both ears. The wounds are powdered with hot ashes from the barracks stove.

Poimet faru (to get a headlamp) is where the winner carves out the loser’s eye with a knife, or pulls it out with his fingers. Usually prisoners who have lost everything, including their clothing, will bet one of their eyes. The eye is then placed on the table for everyone to see.

Criminals might also gamble with the belongings or even the lives of other inmates, with the loser having to carry out the murder on the spot. If the victim was in another cell or section of the camp, the killer had to find a way to reach him — if he refused to carry out his assignment he would be killed himself.

Have you ever gotten reaction from contemporary Russian criminals about the tattoo collections and your published works?

No. While I’m sure they would enjoy our books, today the status of Russian criminal tattoos is not the same. Modern Russian criminals usually view tattoos and other identifying marks as a hindrance to their profession. Contemporary high-ranking criminals attempt to assimilate themselves, and so have become homogenized, with the world of big business.

Although many Russian criminals are still tattooed, these tattoos are usually professionally done, using modern machinery. It is becoming rare to see traditional prison tattoos, made with basic inks (such as soot and urine) and using adapted machinery (windup razors with sharpened guitar strings as “needles”).

In the 1950s, the punishment for wearing a tattoo you hadn’t “earned” might be a beating, rape, or even death. These strict rules around the wearing of tattoos might explain the fascination with this period — tattoos are now focussed around personal meanings and tastes, rather than a strict code with harsh punishments. Russian criminal tattoos have lost their “value,” becoming another piece of flash for tattoo parlors, copied onto vicarious “criminals” around the world. Of course, criminals in modern Russia still tattoo themselves, but the emblems they use reflect their own views and not a coded lexicon.

What’s next for FUEL?

We have just released a book called Spomenik Monument Database, which documents these brutalist abstract monuments to WWII, built in Tito’s Yugoslavia. It is the largest collection to date of these amazing constructions.

We’ve also published a new book called Brutal Bloc Postcards. In contrast to the usual photographs of a ruined and decaying Soviet empire, these postcards depict the bright future of communism: social housing blocks, palaces of culture, and monuments to comradeship. They are at once sinister, funny, poignant and surreal.

“Russian Criminal Tattoos and Playing Cards” is out now via FUEL Publishing, order your copy here

Follow Mike McPadden on Twitter