All images courtesy of Brian Blomerth / Anthology. Photos by Zach Sokol

I first discovered Brian Blomerth’s work on the bottom shelf of a clearance rack at Printed Matter, as the NYC shop was in the midst of moving to its current location on 11th Avenue and 26th Street. Tucked among some zines and artbooks was The Small Dog Other, a 50-page comic about post-apocalyptic dog people tearing ass on motorcycles through a desert wasteland. I can’t remember much of the plot, but one spread featured a Mad Max-looking canine orgy, which became branded into my frontal lobes.

I messaged the contact info listed in the back of the book, and was properly introduced to the psychotic, psychedelic world of Blomerth. It involved his non-stop illustration output, a fake dispute about a dead cat on Judge Judy that somehow aired on TV, a noise music project called Narwhalz of Sound, where the sonic freakouts were conducted using Gameboys hooked up to MIDI controllers, and a side hustle hawking homemade vape juice — “Slippy Syrup,” named after his loyal Pomeranian. (The e-liquid op has since been shuttered, likely by the FDA or DEA. I will miss those Strawberry Graham Cracker plumes…)

He also co-created what is objectively the greatest podcast of all-time: Crafts Conversation.

In 2015, I commissioned Blomerth to create a weekly comic for VICE, where I worked at the time, and we’ve been collaborating ever since. Now, he pens a bi-weekly comic for MERRY JANE about a weed-smoking firedog called Frisbee F.D. The marketing team says it doesn’t get enough traffic, but we’ll run that shit forever. Frisbee makes me laugh every time. Brian also does the lead illustrations for a variety of our features, and he’s always down to hang, especially if it means we can push a deadline. Typically, we’ll drink some beer, maybe hit some whippets, then listen to a cassette tape of an old lady doing vocal exercises for an acting class. Normal stuff.

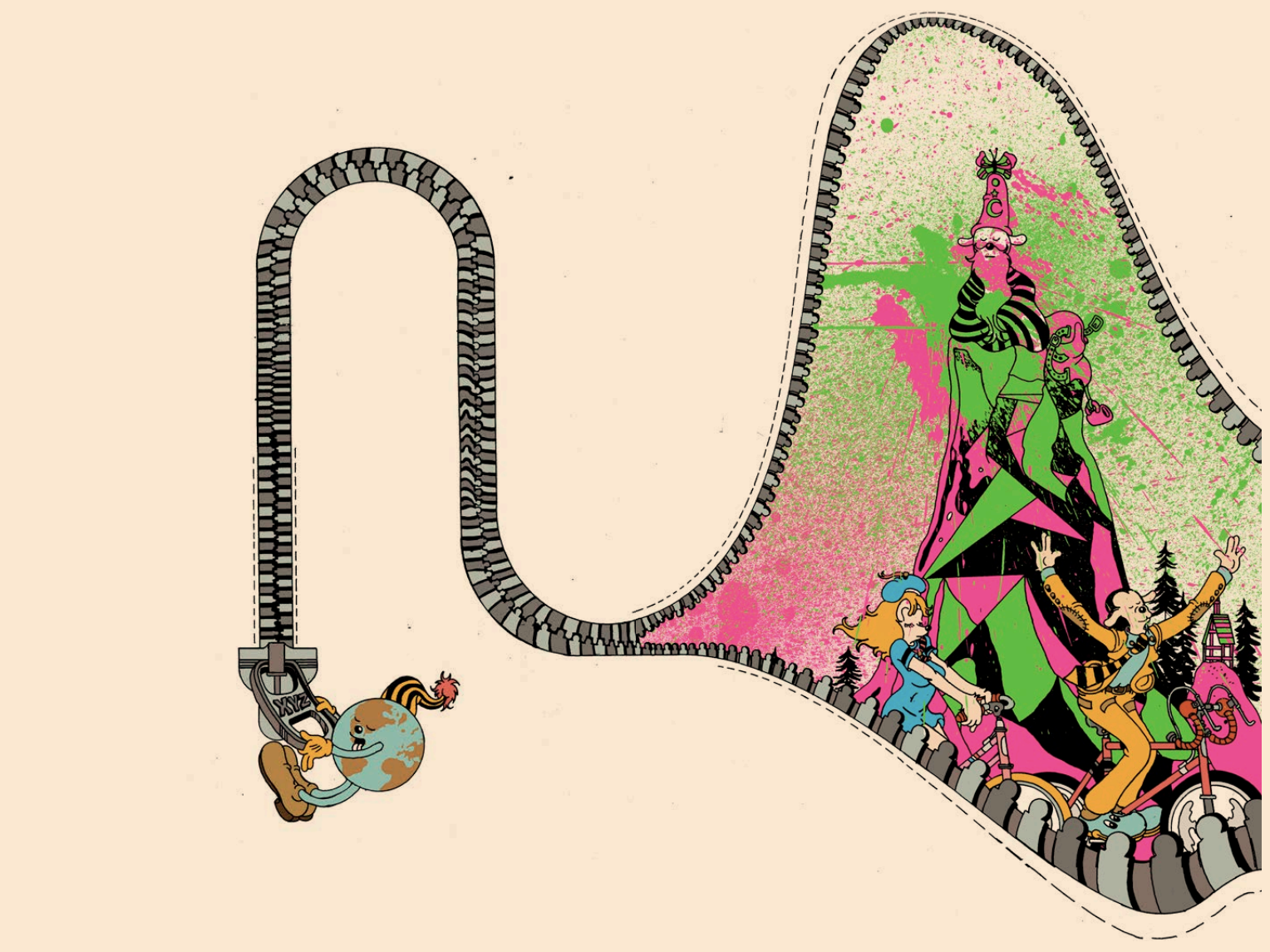

Blomerth has always been a cult-favorite, “a comic stripper” as he describes himself. But his latest project has the potential to skyrocket him outside the freak-o-sphere, to an audience wider than potheads like me. Earlier this summer, the 35-year-old released his longest, most ambitious artbook to date, titled Bicycle Day.

I may be biased, but it is the best graphic novel ever written about psychedelics. If anything, it’s a perfect children’s book about how Albert Hoffman invented acid. And it’s almost sold out entirely. (There are a few copies still available, and Anthology Editions will be printing a second run in October.)

For the unfamiliar, Bicycle Day is the true-story-turned-urban-legend-turned-visual-history of how Hoffman, a Swiss chemist, synthesized LSD-25 while trying to invent an ergot derivative that would work as a respiratory and circulatory stimulant. After Sandoz Chemicals declared the substance ineffectual, he shelved it for five years. Then, in 1943, Hoffman was irked by what he describes as a “peculiar presentiment,” and decided to again experiment on the chemical.

As Dennis McKenna writes in his thoughtful and generous introduction to Blomerth’s visual retelling:

It was this decision, his response to his “peculiar presentiment,” that changed history (and Hofmann) forever. Somehow, in the course of the synthesis (so the story goes), Hofmann was accidentally exposed to what must have been a very tiny amount of the newly synthesized LSD-25. He became nauseous and slightly dizzy. He could not continue his work in the lab and rode home on his bicycle, where he fell into a dreamlike state. His imagination was highly stimulated and a kaleidoscopic cascade of visions crowded in behind his closed eyelids. After a couple of hours, the visions faded.

Three days later, on April 19th, Hoffman consciously ingested LSD-25, this time about 250 µg (approximately 2.5 hits). Whereas no one knows how much he consumed during the accidental dosing, this second dance with lysergics was the first properly documented acid trip in human history. Hoffman ended up riding his bicycle home once again — thus, Bicycle Day — and then had the first acid freakout ever. A glass of milk and the company of his wife Anita “saved his ass,” to quote Brian.

Blomerth details the entire psychedelic saga with ebullient art and accurate historical details. Plus, there’s no page numbers, which imbibes the book with this hypnagogic feel. You can breeze right through it, or get stuck on a single spread for a few hours. It’ll dose your peepers vicariously!

I could write 10,000 words singing Blomerth’s praises and telling you all about why Bicycle Day is his magnum opus. In late May, though, we hung out at his new apartment in Crown Heights and talked about the book in depth while a modular synth emitted bleep-bloops in the background. So I’d rather ix-nay on any more throat-clearing and give the mic to Brian for a lengthy and hazy interview.

OK, one last thought: If Brian Blomerth’s Bicycle Day doesn’t make Hoffman’s fateful discovery a more widely understood and appreciated historical event, only something as dramatic as the decriminalization of LSD will. That’s a win-win, but my point is this book is canon-worthy, even if the psychedelics-specific canon is fragmented and still evolving. Please read it, and then give it to your teenage siblings. You will blow their minds all over their faces, and introduce a new generation to the strangest bike ride of all time.

MERRY JANE: When was the first time you heard the story of Bicycle Day? It’s a “tale that’s been told many times,” as the intro states.

Yeah, that’s true. There’s always somebody in the background that like tells you about it, and tells you about it entirely wrong, you know?

It’s 100% got an urban legend vibe, but it’s a true story. But what really made me want to do this was I watched a video that was just like a documentary on older acid-heads — that kind of deal. And Albert Hoffman was in the doc in the beginning, and he was like, “The first acid trip was terrible. It was a nightmare!”

How old was he when this was filmed?

He was old. Basically the two main stars of the video — for me, at least — were him and this guy David E. Nichols. Nichols is a PhD, and like the foremost fucking PhD on psychedelics, as far as LSD / new substances goes.

So in the doc, everyone is glamorizing the history of acid’s invention, but Hoffman is like, “It was a goddamn nightmare!”

You bet, it was really bad. He thought he was gonna die the whole time; he thought he’d overdosed on this chemical. Some of the dialogue in my book, where he’s like, “Oh my god, my family…” comes from Hoffman’s book, LSD: My Problem Child. It’s just spread out. I also used some material from Mystic Chemist by Dieter A. Hagenbach and Lucius Werthmüller.

But what’s really funny about Hoffman’s general attitude, which comes across in that doc I watched, is how Hofmann doesn’t care much about this whole [Bicycle Day] saga or whatever. At least in retrospect. I write about this in the back of my book, too.

Was he like, “acid was just a fluke”?

He loved it. He really wanted to push it on other creative people, other like fucking European intellectuals. Hoffman definitely thought it was good and important, but he didn’t think his personal aspect in its invention was that important. Like, he hung out with Timothy Leary, and Leary was like, “Let me see the bicycle!” And Hoffman was like, “That piece of junk! I threw that away!” [laughs]

I think it’s like with anything else, where it was just a normal day that got kind of crazy and out of hand.

Hofmann would have people over and be like, “You should try this out. I made this chemical.” Because I mean like he did enjoy it and thought it was interesting. But he calls it his “problem child” because of everything else that happened with it. He did think it had a purpose, had a place somewhere, but like nobody could really figure out what to do with it, you know?

You write in the intro, people often say “he or she wrote the book,” but thankfully no one has ever said, “he drew the book.” What made you want to create a visual history of this narrative?

A.) I thought it was interesting that nobody had done it in this format. B.) the way Hoffman writes it out is so simple. In My Problem Child, the story of Bicycle Day is like three pages long. And it was like, “OK, the way this stretches out is exactly like a kid’s book, like 100%, and it has a whole like Disney arc to it.”

And it takes place in Switzerland, you know?

Oh my god yes; it’s in Switzerland! I’d been wanting to do a weird, like, European book for forever. All the Disney cartoonists, like, Carl Barks did that shit. Donald Duck always went to a location. Herge did this too. It’s taking the viewer (through the main characters) to a remote and, often times, fantastical location. You can’t really do that anymore with the same flair, because obviously it was racist as hell; it was like some colonial-ass shit. But you can go to fucking Switzerland [laughs].

The most neutral place ever.

Completely neutral!

And I love that you write, “I’ve never been there, but I like to think my drawings are accurate.”

There’s a couple parts where you’re supposed to think, oh my god he’s tripping now, and then you go, “Oh no, this is just what Switzerland looks like.” [laughs] Yeah I don’t believe that Europe exists. I’ve never been.

When did the project go from an idea to Anthology commissioning it and the thing becoming a reality?

I wanted to make a singular thing. I was like, If I die after this, at least I have one singular book that I’m happy with. It’s a contained idea, and hopefully it’s an idea that other people are interested in and it works, you know?

And it’s educational, too.

Yeah. I love educational-ass shit.

Well compared to your other books, it is the most family-friendly by far. Even though it’s about the invention of acid.

Yeah. I mean that was the pitch to the coffee shop people. I was like, “Look, it’s a children’s book about acid,” and they were like, “Ok, so that means it’s just weird?” I’m like, “No…” [laughs]

When did you officially start the project, and when did you finish it?

I had the pitch meeting in July, 2018. Then, in fucking August, we went back and forth a little bit on some stuff. In September, I did the research for a month and made a proper outline and shit. This project depended on it being simple, but also having a lot of details from Hoffman’s life. I needed to get it all together.

It’s pretty impressive how much research you did.

That’s the deal, too. I wanted to actually be right in a lot of ways, even though an expert we consulted early on told me the chemistry is wrong in the first part of the book. But that’s like sending an Olympic runner a video of yourself running around your block. [laughs] I did a lot of research, but I definitely could not make acid myself.

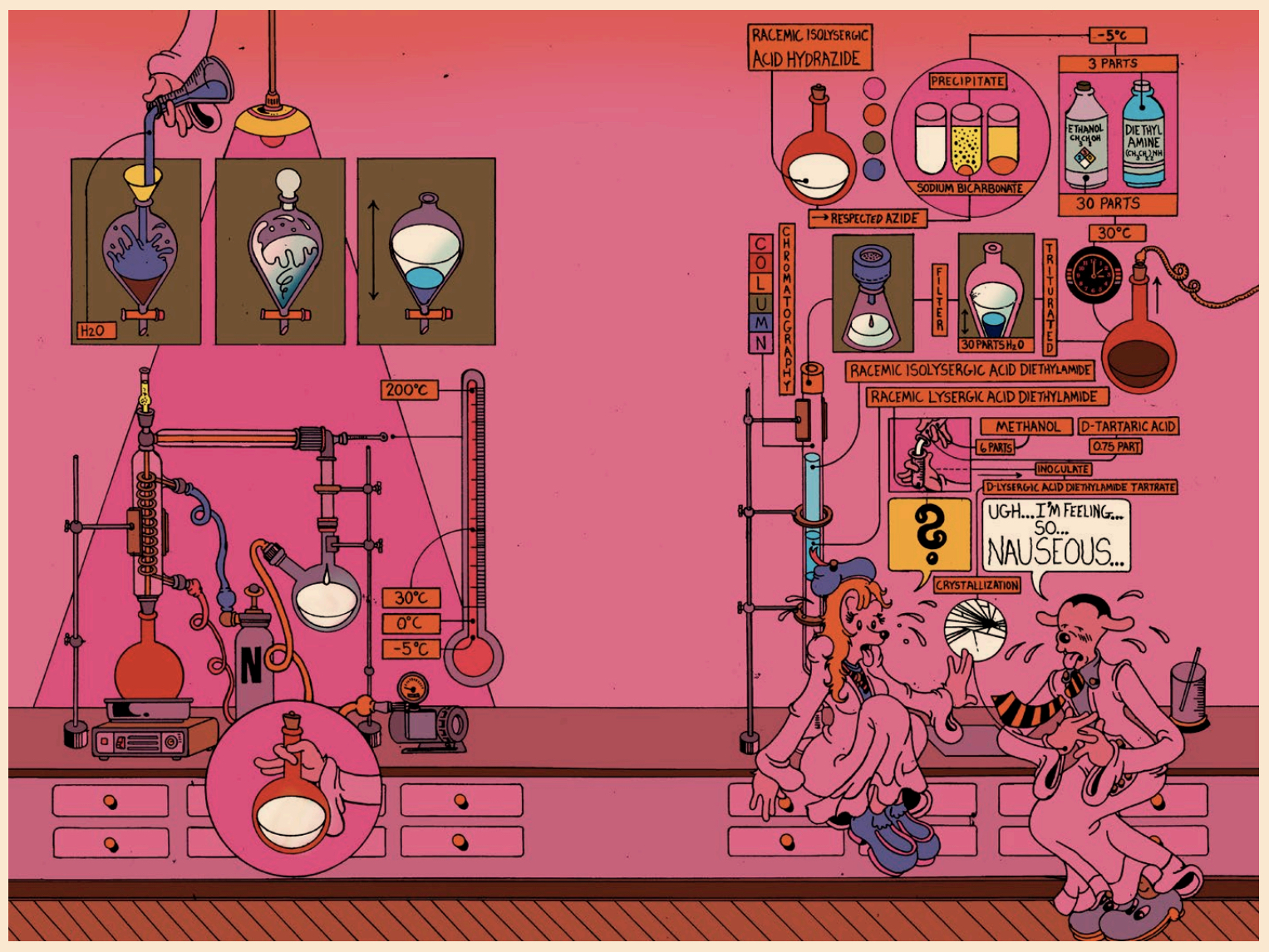

I used Uncle Fester’s Practical Guide to LSD Manufacturing for the chemistry parts. It was like the first widely-distributed pamphlet and practical guide for making acid at home.

It’s not like fucking mushrooms; it’s not an easy grow. The chemistry is fucking complicated for LSD. And the real way to make acid involves chromatography pretty heavily. Uncle Fester goes into that a bit. The section is called “The One-Pot Shot: The Hoffman Method,” and that’s how to make acid if you had all the chemicals, the fucking proper pieces, which Hoffman obviously had.

I read the books we discussed — LSD: My Problem Child and The Mystic Chemist — and combed through every article that had ever been written about Hoffman. Read every interview. The ones closer to the time period are a little better.

So after your one month of research, was it just a mad dash to illustrate the whole damn thing?

Yeah, basically I did the first 70 pages from October to fucking November or December. And then the last 70 or so pages were done from the middle of January to, like, late February. It’s nearly 200 pages. I worked at least 18 hours, every day, for a month and a half. I finished at least two pages every day.

You write in the epilogue that Anita Hoffman, Albert’s wife, is the real hero of the story. But in the actual content of the book, she doesn’t come up too many times. What did you mean by that?

My favorite shit is like a panic attack where you’ve completely lost your mind, and then somebody else comes in and kind of rescues you. That’s the thing I really liked about this story — Anita saved Hoffman from the freakout. This was after he took about 250 micrograms.

Let’s go back to the children’s book idea. It’s not the subject matter that makes it a children’s book, obviously.

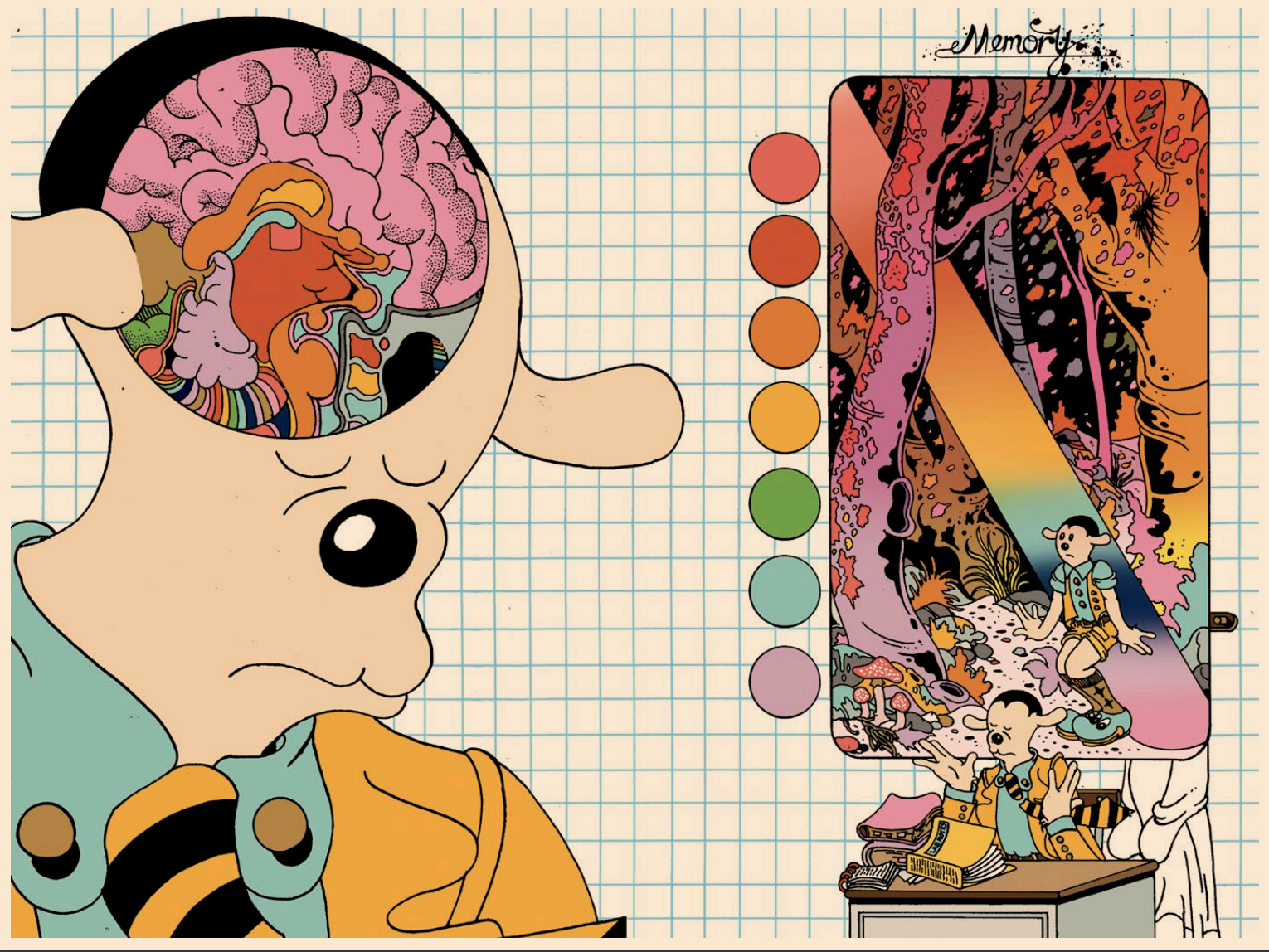

Me calling this a “children’s book” basically means that… any idea from a children’s book that I could half-remember, I kind of threw that into the mix. Like the couch scene from when Hoffman is having his first trip. It’s basically the exact same couch over and over again, where the same image repeats in the various panels. I know that I once read a children’s book where the same exact scene appears, with a repeating couch. I’ve wanted to do that ever since.

I cannot remember the name of the children’s book. That’s the deal. There’s a lot of things that are like references to books that I remember reading when younger. I thought that was pretty similar to a psychedelic experience. I always think the way a kid’s book hits you is psychologically damaging in the same way acid burnout is.

What’s your relationship with acid been like over your lifetime?

Not like super extensive, honestly.

Have you taken it more than three times?

Oh yeah. But not more than a dozen times. Probably like in the middle frame. I like doing psychedelics maybe once a year. Usually, I ride more mushrooms because they’re more available. Acid is an ordeal. Obviously, acid is a way more intense ordeal. And now I know that when I take it, I’m gonna be all stressed out, because it’s gonna be like, “Oh you lied about the book!” [laughed]

The last time I took it was actually pretty funny. A friend of mine found acid that he had from when he was in high school. It was probably 12-to-15 years old. I took it, and thought to myself, Well, if I’m gonna take this high school acid, I’m do the most high school acid trip. I’m gonna go to Central Park! [laughs]. At the park, some dude came over on a Hoverboard with a fucking boa constrictor and he put it around my neck.

So obviously you have an affinity for LSD and drug culture. But what drew you to this history out of all the histories regarding psychedelics?

Obviously, this one has the most fantastical tale of them all. You don’t really know who was the first person to eat a mushroom. Yeah, nobody had to rescue anybody [with mushrooms], either.

Like I said before, I really like the panic attack Hoffman had — that angle of it. Plus, the fact that it was really terrible and then somebody’s significant other really liked him enough to come out and save his ass, even though he was fine, you know? [laughs]

Why are there’s no page numbers in the book?

Yeah, well I wanted it to be like that, where you just flew through it, you know? I wanted it to be like a light read. Also, another rule: always do spreads for anything. Every big idea or event needs to be illustrated in a spread. Meaning a two-page image that you open.

Like there’s a spread when Hoffman gets the milk from his daughter. . The end of the light trip. Both trips did happen in the same week, which is pretty fucking heavy.

Can you clarify which Hoffman trip you’re referring to?

In my research, I called them “light” and “heavy.” Not first or second. Because for the first, nobody knows the amount that he ingested or even how it happened. There’s an aside in the intro where Dennis Mckenna quotes Dr. Nichols. Dr. Nichols is like, “Swiss chemists don’t make mistakes.” So it is very wild he got accidentally dosed. You know about Swiss watches — it doesn’t make any sense. Expertise and quality is the Swiss way. I’m more like a fake Swiss watch, but I wouldn’t have it any other way.

So the first trip was light, and the second trip was heavy.

Light and heavy. The light one he described as having a fairytale quality. It is funny how it actually worked out, where the first trip does seem so much lighter. I wanted it to look like a classic trip.

What really resonated with me is when Hoffman’s sitting on the couch, and little designs start appearing in the corner of the frame. You see little dots, and it reminds me of how hallucinations start with some pulsating and/or geometric visuals.

Oh yeah. This is, like, the classic. This is what I always see. This is what you always see when you’re tripping. Basically, I wanted the first trip, the light trip, to be like, “Oh, OK, I’ve seen this before. This is familiar.”

But what’s funny is those trippy images aren’t sacred geometry or whatever — they’re Amish symbols. Because I have no idea how Europe works. [laughs] I was thinking if I was a US person and didn’t know about European culture — which I don’t — I would think Amish shit is the way to go. They’re hex symbols, and some of the birds are even Amish tree birds.

I also love that milk calms him down at the end of the light trip.

He did drink milk, and then felt a lot better. I thought it was interesting that he really did have milk twice. [laughs] And then later on during the heavy trip, when he’s freaking out, he’s like, “Oh man, it’s a milk problem.” It’s completely insane. Because he really does replicate things that are now known as urban legends related to tripping. Maybe it’s not orange juice, but still.

Hofmann does really love milk; he drinks milk earlier in the story, too. I drew his actual lunch. The details were in his book! He wrote what he ate on the day he decided to experiment on LSD-25 again. He put honey and butter on toast, and then drank milk and that was his lunch! [laughs].

It felt like a children’s book. It felt like Disney shit, like the old Disney shit — the classic Disney ones. It even had the same narrative arc as Disney stuff and fucking children’s book stuff. I was like, How is there not a book like this? I knew I had the right idea for a pitch meeting, and thought, “If somebody comes up with this before me — I’m ruined!”

The chemistry equipment illustrations are truly impressive, even if fantastical at moments.

I do know the names of the chemistry equipment. [Points to a specific page] But that’s nitrogen right there. There’s another part for the whippets-heads, but you have to guess which. The editor didn’t notice it until three weeks after I submitted. [laughs]

Writes a whole book about acid, throws in a whippets reference….

Yeah, you got to, you got to…

Explain what the part is, I love this page. He says to Susi, “Ugh, I’m feeling so nauseous” and the spread is all pinkish-red.

This is when he accidentally doses. The light trip. Yeah, this spread I copied from the patent, so I think the chemistry is more accurate.

The other thing I really like from kids’ books is when it gets all The Way Things Work on you a little bit, you know? You ever check out The Way Things Work? It was my favorite type of book as a kid. It’s like a book that shows you an airport, and then there’s spreads of like, “How does your luggage go from the plane to the tarmac? There’s a guy who brings it over!” And then it shows the tarmac. It’s WikiHow for kids.

So I was hoping that some of this chemistry would work in the same way. It’s so hard for the non-chemists to even get access. ‘Cause basically, this acid stuff is like graduate-level chemistry. For my dumb ass to even get close is very twisted.

Bicycle Day, especially being the day before 4/20, is often overlooked. I think this book could actually help make it a more understood and respected historical event.

I hope so. I mean that was kind of the goal. But it was also that I really like Hoffman as a person. He’s like a really very specific, very non ego-centric person, which I think is great. He’s also a reluctant inventor — it’s really awesome. I loved his book. I love that he had a hard time with his invention. And I love that his wife helped him through the panic attack. So, basically, I loved every part of this story.

This hits every notch on, like, “The One Book I Want to Do Before I Die,” you know? It has every weird, involved thing I’ve been thinking about for years. I think this book would be cool for teens. If I was a teenager, I’d be like, This book is insane…

Before I forget, can you talk about the significance of the “mystical experience” Hoffman had as a child.

He talks about this all the time. He never says what happens, which I love too. He’s really tripped out to be like, “Oh yeah, I had this experience in the woods,” but then never explain it. He would reference an Aldous Huxley book that talked about mystical experiences throughout the ages. Hoffman and Huxley both thought that mystical experiences were a way to deal with modern life that people forgot about. They thought that mystical experiences give your life purpose. A mystical experience that points your life in a direction. Which I believe in 100%, as well. It’s good to have fuckin direction. Or at least a goal, you know? And that’s what one of those experiences will give you.

Like when I was a kid, I went to church all the time. There was one Sunday where I swear to God, I had my whole life flash in front of my eyes as a child. So many weird things about it I couldn’t understand at the time and now they make sense in retrospect. I’m like, Oh I’ve seen this before, as a kid! And this whole thing happened, but it didn’t make any sense before. Now it makes fucking sense. It’s fucking all in there, and it’s so weird. There you go.

That’s the same reason why I wanted to do this as a kids’ book. Let’s tie this conversation all fucking together. That’s the same reason. ‘Cause a childhood memory? It’s the same sort of idea that comes with acid. And if I’m gonna hit every angle, this is the way I want to do it, you know? I do it in my weird way.

When I really researched the story, I was like, Oh, this checks off every box I’ve wanted to do for forever. Let’s just fucking try it out. It was like, if I died tomorrow, at least I did this one book. I’ll be OK. If I die, that’s it. I did it.

To order “Bicycle Day” when the second run comes out, visit Anthology Editions’ website here

And check out Blomerth’s personal website and Instagram