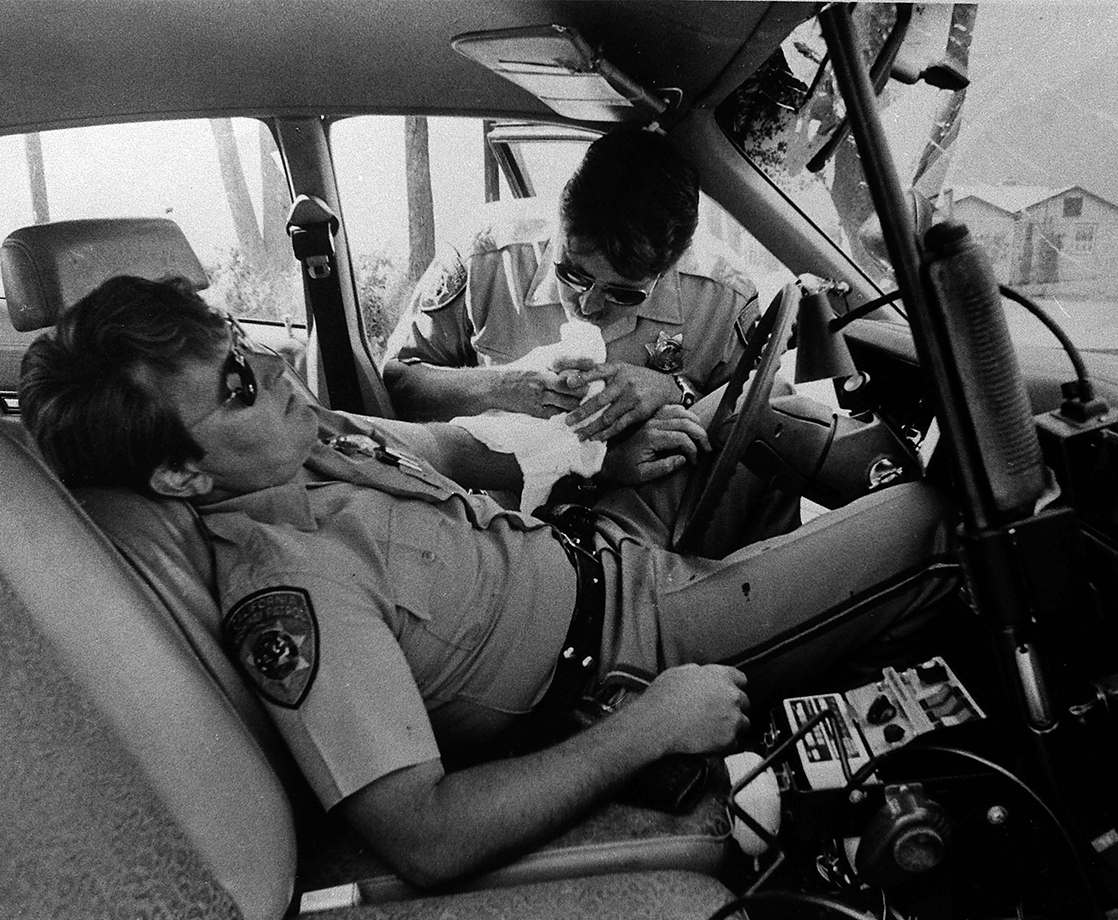

Lead photo: CHP officer Doug Earnest bandaging wounded patrolman Bill Crowe (RPE/Jim Edwards)

On May 9th, 1980, five men with automatic weapons and 12-gauge shotguns kidnapped a man, stole his van, and planted a homemade bomb at a gas station. The DIY explosive served as a distraction before the crew robbed the Norco Security Pacific Bank in Riverside County, California for $20,000.

The criminals then engaged local law enforcement in a shoot out that spread across 23 miles, up into the San Bernardino Mountains. Thirty-three police cars were destroyed or damaged in the chase, eight officers were wounded, a police helicopter was shot down, two of the culprits were shot dead, and one officer was killed, before the other three robbers were finally apprehended. The bank robbery was one of the most violent heists ever, and it led to nationwide changes on how police pursue and confront armed suspects.

A new book, Norco ’80: The True Story of the Most Spectacular Bank Robbery in American History by California native Peter Houlahan, looks at the story in excruciating detail. Not only did Houlahan interview many of the officers involved, he interviewed the three robbers who are serving life sentences for their crimes.

Above: Bolasky’s vehicle at Fourth & Hamner. 32 police vehicles were destroyed (RSO)

In chapters like “The Jupiter Effect,” “Ambush,” and “Bricks in the Wall,” the author looks at how the trends of the times, including popular religious groups like the Jesus Movement, led to the over-the-top heist and its aftermath. The book also examines the actual firefight in depth, and analyzes the trial of the “Norco 3” (as they were called) from the vantage points of both the cops and defendants.

MERRY JANE talked to Houlahan to find out why he decided to write a book about the violent caper, its effects on the police involved, and how the defendants were able to dodge the death penalty. He even discussed how he developed a relationship with the culprits themselves. The author may have been 17 when the crime occured, but he remembers reading about it in the news, and explains why it stuck with him for so long. Here’s what Houlahan had to say about the Norco 3.

MERRY JANE: You first heard about this story as a teenager, so why did you decide to write a book about it now?

Peter Houlahan: I grew up out in Whittier, California, which is only about 20 miles away from Norco, where it took place. I was very aware of the event when it happened. I was a bit of a news junkie, always reading the LA Times. I opened up the paper on Saturday, May 10th, 1980 and there was this big picture of a wounded California Highway Patrolman being bandaged. Just this amazing story about these guys who’d committed this bank robbery and gone on this crazy chase. A helicopter [was] shot down and they ambushed the police. The surviving bank robbers were still at large and disappeared into the canyons of Lytle Creek.

On Sunday, there were photos of Russell Harven, Chris Harven, and George Wayne Smith. They looked like just the craziest outlaws in the world. I followed the story. I knew nothing about the trial at that point or even until I started researching years later, but [the story] always stuck with me. I’d tell people about it and people would always respond with, Wow, did that really happen? How come I don’t know about this? When I settled in and decided I wanted to write something, I kind of knew that Norco was going to be it.

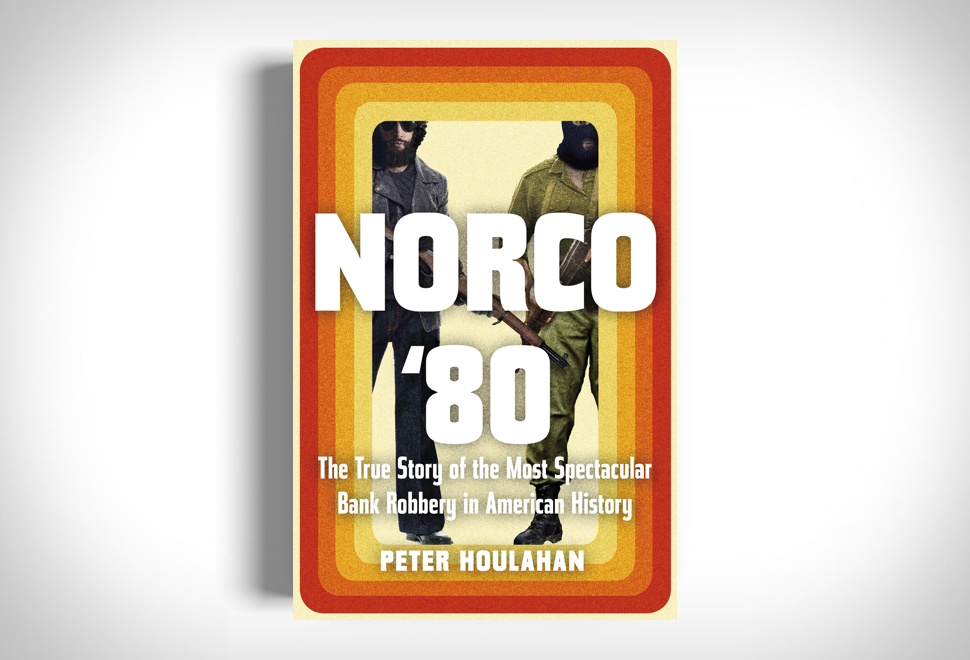

Above: Sketch showing the position of the shooters in their yellow truck during the pursuit (RSO)

What turned this group of landscapers into bank robbers on a mission?

It had been a tumultuous decade, and doomsday scenarios were very popular. In the ’70s, there was definitely a feeling of [not being] happy with the status quo. People were not happy with police, and kind of felt like anything goes. Now, obviously, most were not robbing banks or turning to a life of crime, but it was a very volatile era. One of the major influencers, at least certainly on Smith, was what was known as the Jesus Movement.

This was the huge, youth-oriented, aggressively evangelical, “born again” Christian movement that really came out of Orange County. There were these megachurches and youth-oriented ministries that focused heavily on the Book of Revelation, the ideas of the Rapture and the Second Coming, as well as all the catastrophes and cataclysmic events that would precede it and lead to the collapse of society.

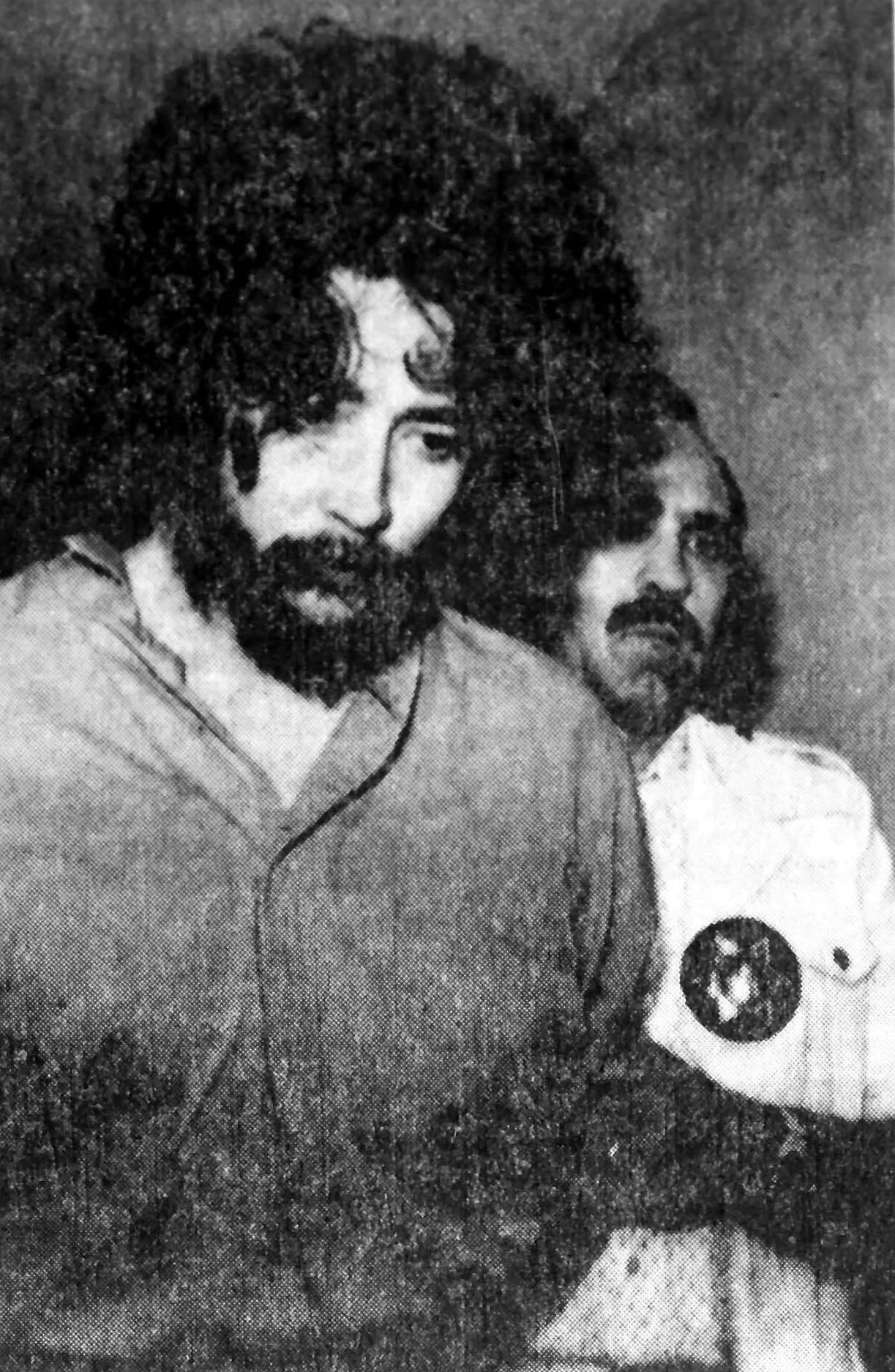

Above: George Smith under arrest (RPE)

So George Wayne Smith fell hard for these prophecies. What else was he like as a person?

After seven years of tribulation, George Smith became involved with those churches, particularly Calvary Chapel, at a very early age. He joined the military and was stationed in West Germany, near the Iron Curtain, and was trained in nuclear tactical battlefield weapons. He was an artilleryman. The volatility of the Cold War at that period, and the threat of nuclear weapons, was very heavy.

He also had big downturns in his life. He lost his job, he lost his family, he was running out of money. George Smith had a vision of himself as destined for great things. He was the guy who would always swoop in and try to save the people around him by converting them to Christianity so that they would survive the Rapture. He had a real grandiosity about himself; nothing George did was small. There was a big cognitive dissonance between the person he saw himself to be and the person he was at the time.

During the actual robbery, how were the cops outgunned? Can you talk about the weaponry that these guys had, and how the standoff made law enforcement rethink their rules of engagement?

Norco is widely considered to be one of the gateway events leading up to what is now referred to as the militarization of local police forces. The bank robbers were armed with civilian versions of military-grade weapons. They were essentially high-powered semiautomatic assault rifles with high capacity magazines, and they had pulled together thousands of rounds of ammunition. All of this was legal. They bought it legally, and they possessed it legally.

What was not legal, of course, were the fragmentation grenades that they made in their garage using The Anarchist’s Cookbook. But the sheriff’s deputies, at that time, were armed with the same weapons they had been guarding the Wild West with for 100 years. And that is a six shooter and a Winchester shotgun. And they were absolutely no match for the level of firepower that was brought against them, which included fragmentation grenades being thrown out, but also an estimated 1,700 rounds of ammunition that were shot at them. They had vehicles that were being hit from a half-mile away on the freeway.

Within a year, Riverside and San Bernardino [law enforcement agencies] had put in an order for about 150 fully automatic Ruger Mini-14s. They also began to move from these revolvers, six shooters, to semi-automatic pistols — sidearms that could fire up to 15-17 round magazines before they had to switch out. There were many steps along the way to what is now the situation with how police forces are armed, but Norco is certainly considered a gateway event in leading towards that.

How did the bank robbery affect the deputies and responders? They experienced PTSD, which is a big issue now, but wasn’t so back then.

At that time, law enforcement was not aggressively addressing the impact of traumatic events that happened on the job. There’s a lot that just happened in routine police work, and this was, of course, rather extreme. The most terrifying thing was being under fire from these weapons, and almost all the cops freely admitted how terrified they were, how helpless they felt in terms of being able to fight back. And then they lost a fellow deputy. Some lost their marriages, some lost their careers, some of them were certainly haunted by the heist for years and even to this day.

What was the trial like and how did the Norco 3 beat the death penalty?

This trial was one of the first death penalty trials in California, and certainly Riverside County, after they re-instituted the death penalty several years before. The judge was very cautious to avoid anything that could overturn it later on, or be used on appeal. The criminals had three defense attorneys that were just battlers, and they all believed that the judicial system is generally stacked against the accused. It became extremely contentious. There were open outbursts. They threw pencils at each other in there. They challenged each other to fist fights.

George Wayne Smith’s defense investigator, Jeanie Painter, was a very attractive 33-year-old investigator who was considered extremely good, very experienced on felony cases. Through the course of all this, she began to have a relationship with Smith. She was accused of jailhouse sexual misconduct, bringing in drugs, bringing in naked photos of herself, and after his conviction the two were married for a few years. She crossed paths with a very persuasive, fairly manipulative George Wayne Smith, and really kinda fell prey to that situation.

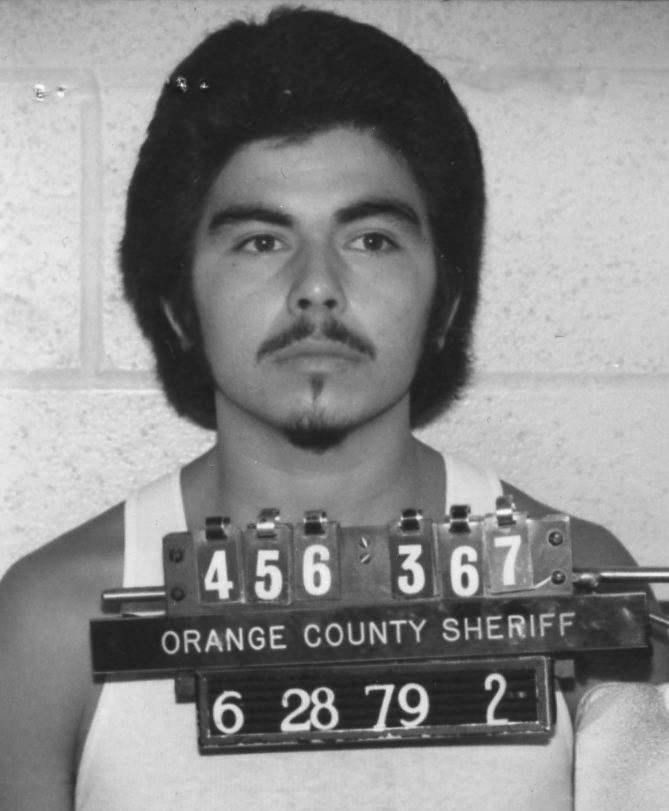

Above: Mug shot of Manny Delgado from previous minor arrest (Orange County Sheriff)

You interviewed the Harven brothers and Smith right? What did those interview reveal to you, and how did they impact the book?

Yes, I interviewed Chris Harven up in Vacaville, and Russell Harven in Lancaster Penitentiary. I wrote letters back and forth with George Smith, but he kind of declined to really be involved heavily in the making of this book. But I certainly spoke with family members and things like that. Chris and Russ were both very candid. Both very clear-eyed about what they’d done, and they were very bitter about the trial. I was able to spend quite a few hours with them in the prison visiting room, and I continue to write letters back and forth with them now.

Have the robbers showed any remorse or anything like that in your communications with them?

It’s kind of mixed. George Smith had a few opportunities to demonstrate remorse. Whether he felt it or not, he kind of declined to [express that]. My first correspondence with all these guys was them raging about the injustice of this trial. Now, they knew what they had done, but they felt like first there was massive misconduct on the part of the police officers and prosecutors. They believed that they were not responsible for the death of Jim Evans, the cop. They said it was friendly fire from one of the other officers, and therefore they felt that they should not be in prison any longer.

I asked Russ Harven if he thought they were the ones who killed Evans, and he said, “God, I hope not.” And Chris Harven mostly has remorse for what he did to his own life. But in the end, George Smith wrote me a letter. I said, “Look, I’m writing the epilogue, and I just want to give you every opportunity to express how this has impacted your lives and the lives of others.” And he responded, “I am very sorry for this. I think about it every day. I know I owe an apology to the Evans family, as well as the Delgado family.” I think he’s remorseful, but he’s a complicated guy. He certainly has this psychological makeup that in many ways deflects responsibility for what happened that fateful day.

For more on “Norco ‘80,” order the book online via Counterpoint

Follow Seth Ferranti on Twitter