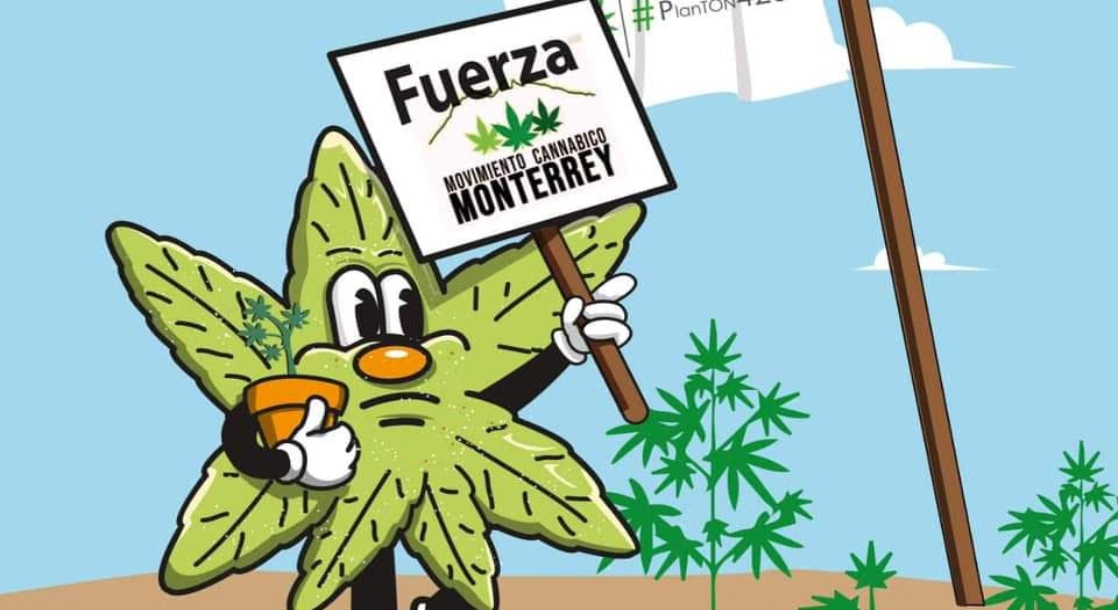

Flyer made by Jualdi for cannabis activists in Monterrey, Mexico (Courtesy Plantón 420)

Illustrator Juan Jose Marroquín, aka “Jualdi,” lives in an art-covered apartment in Mexico City’s Buenavista neighborhood. Like the Mexican capital itself, the architecture of this vecindad, or patio-sharing apartment building, features an amalgamation of architectural styles spanning multiple eras. From the street, the complex presents a 1950s-style aesthetic. But by the time you get to Marroquín’s home, located deep inside the building, colonial-era beams line the ceiling. They add dimension to a living space studded with artwork by some of CDMX’s best-known artists in the comics, street art, and tattoo world.

The tall, broad-chested Marroquín sits on a small stool at a tiny wooden desk in the apartment’s foyer. The space doubles as his art studio, the birthplace of an entire universe of cannabis creatures. Serving as the guardians of this alchemical pen-and-paper process are the adorable psychedelic rapscallions of long-time sketching buddy Tysa Paulina, which peer impishly out from the wall alongside drawings of masked figures by the Estado de México contemporary folklore artist Saner. A wide-eyed, hammered metal creation from Marti Guerrero’s Tim Comix line gazes at visitors as they enter Marroquín’s space. A needlepoint tribute that artist Mario Muñoz stitched to honor the illustrator’s weed nug rendition of Hayao Miyazaki’s woodland character, Totoro, is positioned to peek over the illustrator’s shoulder while he draws. On nearly every wall hangs framed editions of Marroquín’s originals, including nugs wearing helmets riding motorcycles, dinosaur nugs, and Japanese-inspired buds wielding katana swords.

Juan Jose “Jualdi” Marroquín at home in Mexico City (Photo by Caitlin Donohue)

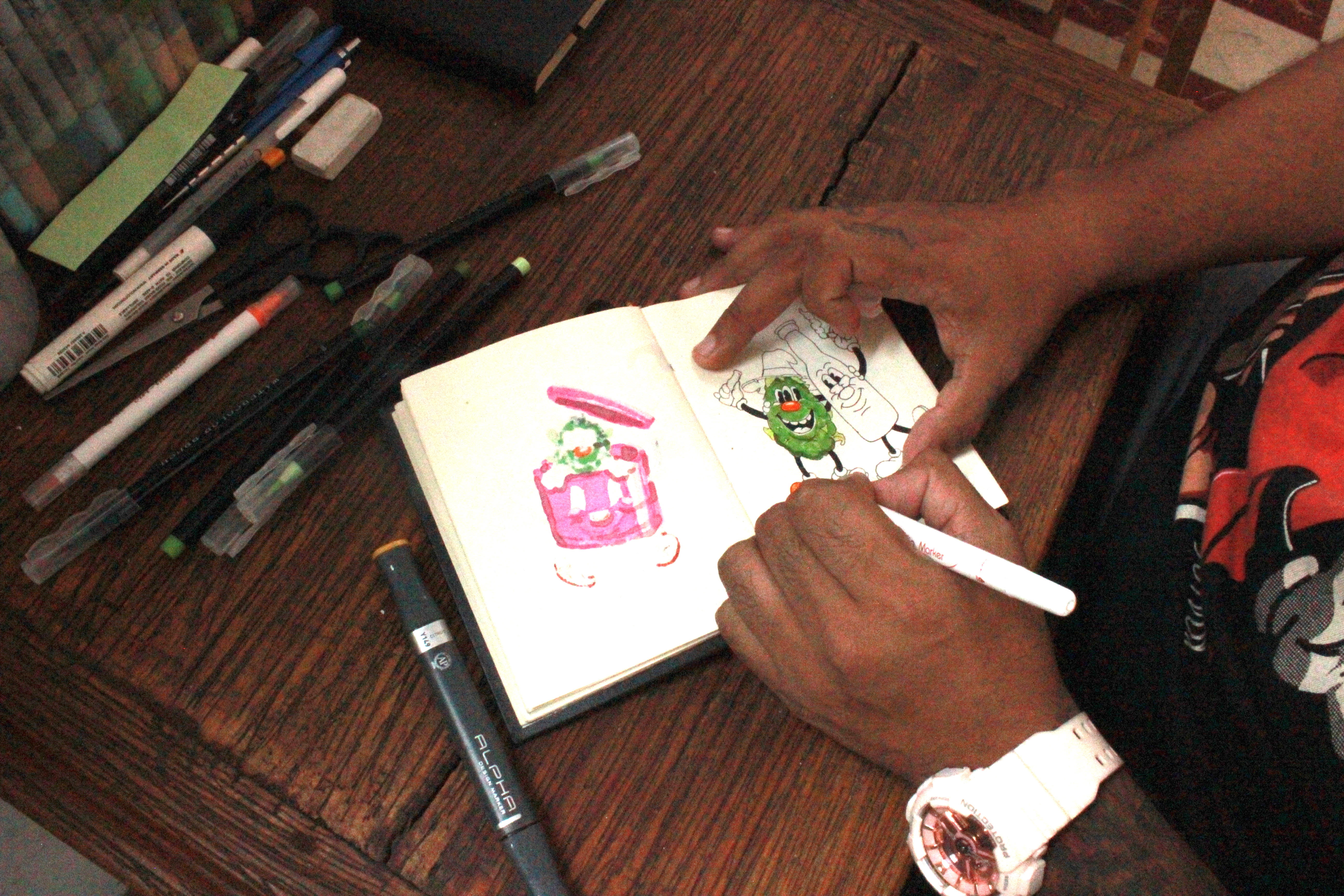

The creative energy in Marroquín’s space is palpable. Adding color to a recently-sketched, jovial nug and beer bottle drawing he worked on for a CBD-infused cervercería, he reflects on the powerful role that marijuana illustrations have played in Mexico’s cannabis activism.

“Illustration is important for this movement because images are the starting point for any project,” he says, the words coming quickly and easily despite the joint making its way around the narrow room. “A brand, a social movement — they have to have a well-done concept, but at the end of the day in marketing, it’s all about the visual. Just look at your own consumption. Your first interaction with a brand is with its box, its bag. Later, you can find out that the product wasn’t that great — but that’s marketing. Social movements are the same.”

Underlining his point, Marroquín breaks out one of his little black books filled with his most popular cannabis characters, many of which are drawn in a wide-eyed style resemblant of the 1950s Disney-era. Nugs boasting sweet gazes and peppy, anthropomorphized smoking paraphernalia fill the pages. Marroquín’s kush-y twists on beloved animated Japanese personalities, from Sanrio’s Keroppi to Studio Ghibli’s No-Face, also show up throughout the book. The most recurring face in the pocket-sized volumes is El Comandante, the affable pot leaf Marroquín created for Plantón 420, the cannabis protest camp outside the Mexican Senate. Marroquín has rendered El Comandante at least a dozen times for the camp, a site that has emerged as the country’s focal point for cannabis activism.

Jualdi and El Comandante (Photo by Caitlin Donohue)

The pervasiveness of El Comandante on activists’ t-shirts and protest flyers across the country reinforces Marroquín’s faith in the power of images to reflect the ethos of social movements. In fact, Plantón 420 uses the character in flyers for its workshops, which places a premium on training cannabis activists in other cities around Mexico to lead a nationwide fight for users’ rights. The group’s Popular School of Cannabis Activism [EpaCann] will convene for the seventh time this summer to educate marijuana consumers on human rights and drug policy, as well as activist skills, such as first aid. The country’s organized cannabis movement is growing exponentially as a result of these educational opportunities. Marroquín’s Comandante now adorns protest flyers made by EpaCann graduates in Puebla, Monterrey, Baja California, and in other Mexican cities and states.

Some activists have even bootlegged their own versions of El Comandante, who has popped up on cannabis protest flyers from Brazil to Spain. Far from feeling possessive of his creation, Marroquín calls the plagiarism of El Comandante “really beautiful stuff.”

“I knew sooner or later that the design was going to be the property of everyone,” Marroquín says. “I wasn’t going to mess around with author rights,” he says, adding that most cannabis activists looking to utilize his work are “very respectful.”

Plantón 420 activists wearing Jualdi designed shirts (Photo courtesy of Plantón 420)

His all-access approach vibes well with the historic importance of illustrations to cannabis and drug culture. Underground comics have long helped define emerging subcultures, including the weed-centric comics that surged in popularity during the ‘60s and ‘70s. The counterculture publication aesthetic came to define the experience of smoking weed for many, like Gilbert Shelton’s “The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers,” which is being made into a star-studded animated series starring Woody Harrelson and Tiffany Haddish. The continued relevance of this art style is further proven by the 2019 sale of the iconic 1971 face-melting, six-image strip titled, “Stoned Again!” by countercultural cartoonist R. Crumb. It went for a whopping $690,000.

Today, artists continue to carry on the responsibility of providing us with smoke-filled strips, like Simon Hanselmann’s stoner cat and witch duo, the blunted protagonists of her Megahex series.

In Mexico, illustrated characters have long been the ambassadors of weed culture. That legacy has roots in Don Chepito Mariguana, the cannabis-consuming, woman-chasing, Mexican Revolution-era protagonist created by José Guadalupe Posada, the famed lithographer and political parodist from the 20th century. Modern artists like Tysa, Wina Obake, Malas Costumbres, and Lukas Alienigena now create joint-toting cat and alien avatars. The color-saturated pages of Mota Comix often feature strips inked by Señor Berumen, creator of sexualized female protagonists that represent the drugs themselves, like superheroine Marihuanella and the questionably panty-baring psychedelic schoolgirl, La Psilucibiniña.

Created in the Estado de México community of Molinito, Naucalpan de Juárez in 2017 by editor José Arizaleta, Mota Comix intersperses drug-inspired comic strips with informational articles. The publication tackles subjects from the therapeutic uses of raw cannabis to the latest political progress towards national cannabis legalization.

The potent blend of art and information is intentional, says Arizaleta. “If you try to change politics directly, you get a reaction,” he told MERRY JANE via text message. “If you change culture, you change politics. Art is a non-biased universal language that speaks directly to the soul — that’s why it’s so dangerous and powerful. Velvet outside, iron inside.”

Marroquín has always been uniquely attuned to the power of art. He went from being a kid who wouldn’t stop drawing to a full-blown graffiti artist, an anonymity-friendly genre that gave him an opportunity to make art without being defined by identity. “My artist name ‘Jualdi’ is super asexual,” he says. “For a long time, I didn’t show my face, and people thought I was a woman. I like that art is not about gender.”

But Marroquín is now a well-known figure in Mexico — in fact, it’s tough to escape his work in Mexico City’s weed world. Many of CDMX’s best-known cannabis groups and brands have enlisted him to create their visual identities. This involvement with the community began when Marroquín’s best friend from high school, the now-deceased cannabis activist Jasiel Espinosa, brought on Marroquín as designer after co-founding one of Mexico’s first public cannabis clubs, Club Cannábico Xochipilli. Marroquín created an upturned god face logo for Xochipilli and created the visual identity for its CBD-focused sister organization Fundación Ananda, as well as the club’s Radio Pacheco [in English, “Stoner Radio.”] He’s done design work for a women-run cannabis bazaar called 420Neny and an edibles brand known as Mamaponcha. He has collaborated on a ‘toon-faced bong for a ceramic stoner-ware line called Talaveria Cann, and he has an upcoming clothing collaboration with CDMX streetwear line, Materia Lab.

But listing off Marroquín’s design achievements misses the extent of his impact in the cannabis space. Marroquín is also a 420-friendly tattoo artist, and co-hosts a hip-hop and weed show (“Rap y Yerbas” or “Rap and Herbs”) for marijuana media platform, Jotvox. With his partner, he operates a drug analysis equipment sales brand The Weed Laboratory, one of a handful of Mexican companies selling gear capable of testing everything from cannabis-growing soil pH to contaminants in one’s cocaine.

As immersed as Marroquín is in the various branches of weed culture in Mexico — a country where many still harbor Reefer Madness-infused misconceptions about cannabis — it follows that he’s focused on the power of art and how it can help educate people on the plant’s many benefits.

Many weed illustrators who came before Marroquín depicted ganja highs in an excessively freaky, deranged manner. That’s why Marroquín has his eyes fixed on making his images relatable and accessible to all allies in the cannabis legalization movement. His original concept for Plantón 420 was a Six Flags-style arch to welcome visitors, and human-sized cardboard cut-outs of El Comandante highlighting the protest camp’s basic rules (which are no alcohol and no drug sales of any kind) and as a photo opp for the public.

“Stoners don’t like to follow the rules,” Marroquín says, laughing. “But if it’s a cartoon character telling you not to drink alcohol, you’re going to pay attention.” His joyful nugs and leaves also serve to make the message of decriminalization more accessible to a wider audience less attracted to hardcore stoner imagery. “We don’t want to be seen just as fighters,” he insists, talking about his fellow cannabis activists. “We’re also friends!”

Jualdi’s sketches (Photo by Caitlin Donohue)

Importantly, given the history of the animated cannabis genre, Marroquín’s ‘toons work against a certain outdated perception of stoners. Not all cannabis consumers are dudes, after all — or overtly-sexualized stoner goddesses. “I try to make it so that the nugs don’t have genders,” Marroquín says. “Often in the 1950s, ’60s-style that I specialize in, making something feminine means drawing it in high heels and with a bow. And look; I don’t like that, it doesn’t represent my way of thinking, and people who consume, it doesn’t represent them either.”

His approach signals a new tactic in Mexican cannabis activism, one that recognizes the importance of all types (including genders) of consumers being included in the legalization movement in order to marshal the most political will possible. Call it the urgency of being “friendly,” as Marroquín often does. “A lot of the time, there’s a lot of men at these cannabis events, too much testosterone,” he says. “I like for the illustrations to be friendly. Being a stoner is not about your gender.”

Is this the happiest place on Earth, when it comes to weed art? Marroquín chuckles over an assertion that he is the Mexican Walt Disney of marijuana. “I’d like to be,” he says. “I’d like to have a marijuana theme park, that would be amazing.”