Photo courtesy of US Attorney's Office, Eastern District of New York / Citadel Books

In the early morning hours of December 11, 1978, armed thugs made off with close to $6 million in cash after executing a well-planned robbery at JFK airport in New York. Known as the Lufthansa Heist, the crime was the largest cash robbery ever committed in the United States at the time. Even though the caper’s been romanticized in the Martin Scorsese classic Goodfellas, a lot of the details of the crime have gone unreported. Jimmy “The Gent” Burke, whom Robert De Niro played brilliantly in the film, was the acknowledged mastermind of the heist, though he was never charged with the crime. But in 2015, an aging Bonanno Capo named Vincent Asaro was brought to trial for the robbery, three decades after it was committed.

The career mafioso is the subject of a new book, The Big Heist: The Real Story of the Lufthansa Heist, the Mafia, and Murder, by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Anthony M. Destefano. After attending Asaro’s 2015 trial — where the feds tried to convict the 80-year-old mobster for charges relating to the Lufthansa Heist — Destefano decided to pen a book and give the real story of the highly mythologized mafia legend, aided by interviews with Asaro and some of the other mafiosos.

The book also covers new details concerning the planning of the robbery, as well as how prosecutors tried to go all-out when convicting Asaro through eyewitness testimony from mob turncoats Gaspare Valenti and Salvatore Vitale. With chapters like “A Goodfella Laments,” “Dead Fellas and Gals,” and “Dead Men Told No Tales,” Destefano takes a hard look back at the Bonanno and Lucchese crime families from the Donnie Brasco era, when being in the mob meant something, and when guys like Asaro could make a fortune just by being connected. The author even got input from Asaro — the first time the gangster has ever spoke about his role in the heist. MERRY JANE chatted with the acclaimed reporter by email about what covering organized crime for three decades has taught him about the Mafia, what movies like Goodfellas and all the reports on the heist got wrong, and if Asaro's fading influence in the criminal underworld is representative of the Mafia’s decline in America.

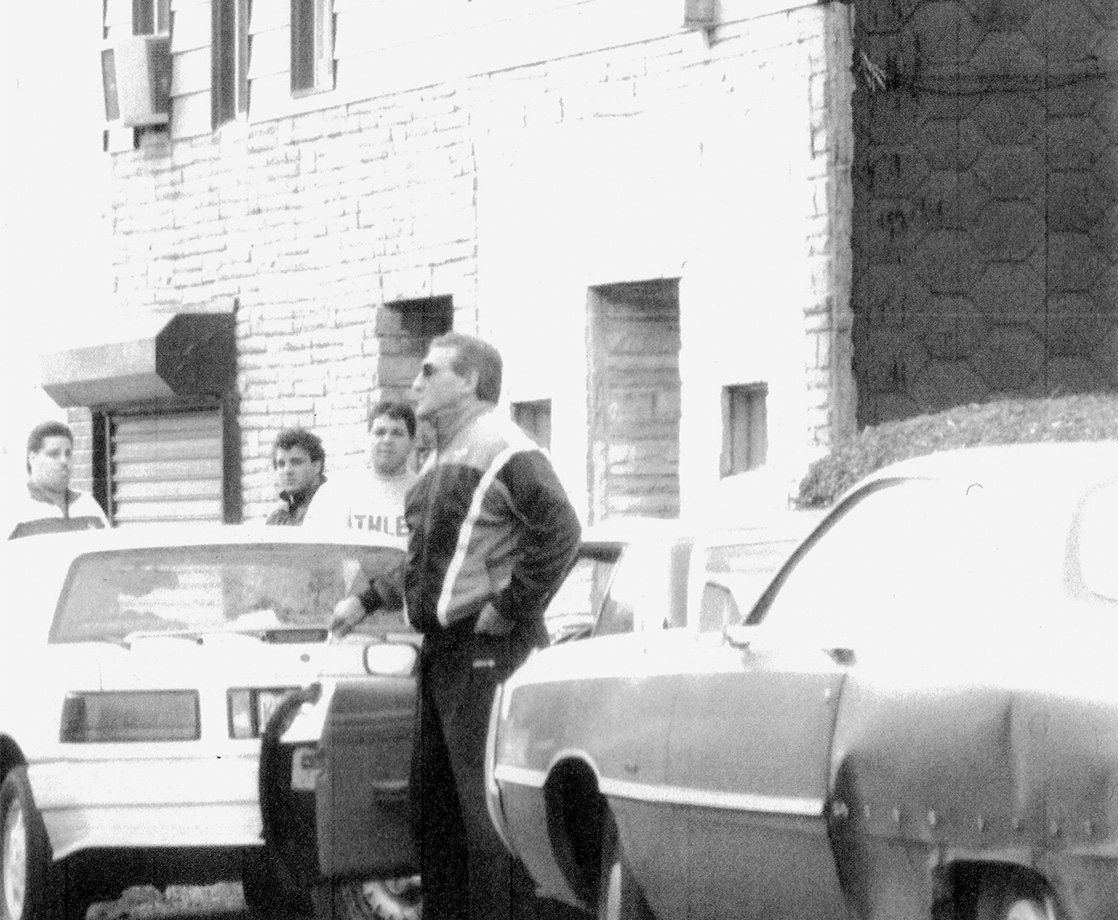

Vincent Asaro (center) walking down an alley that led to a Bonanno family social club on Grand Street in Maspeth Queens. Photo courtesy of US Attorney's Office, Eastern District of New York / Citadel Books

MERRY JANE: Why did you decide to write a book on the Lufthansa case?

Anthony Destefano: After the trial of Vincent Asaro, I believed it was now time to write the definitive history of the crime with the most up-to-date information and intelligence. The 2015 trial laid out a lot of new information. Based on what has been disclosed in recent years about the Bonanno family, I thought the narrative could be made more extensive, with more characters added along with more perspective.

You’ve written about organized crime for over three decades. What have you learned about the Mafia in your time reporting on the subject?

A great deal, although I learn all the time what I don't know, particularly about the history. The Mafia has a significant place in the history of the country and it once controlled a lot of money, influence, and of course had power. The Mafia valued loyalty in the old days, but money was always a driving force. As time went on, money and self preservation became more important than any sense of kinship among the Mafiosi. Covering the Mafia has shown me the value, as a writer and journalist, of having a good institutional memory in covering organized crime, something that gets lost with journalists today.

What was it like attending the Vincent Asaro trial and hearing new details on the heist?

It was eye-opening, for sure. We knew the broad outlines of the story, but the trial gave us so many new details and introduced new characters. Trials are often long periods of boredom, interspersed with some sudden dramatic moments. We had that in Asaro. The verdict of not guilty was of course the major dramatic moment. I thought he might get convicted, but saw a way that he could beat the case. The courtroom reaction of all the participants is one I won't forget. Asaro was beyond happy. Months later, as I interviewed him, Asaro was still an angry man for what he had gone through.

Vincent Asaro (center) at a funeral home in Ozone Park, leaving the wake of a friend. Photo courtesy of US Attorney's Office, Eastern District of New York / Citadel Books

What did the movies like Goodfellas and all the media reports on the heist get wrong?

It wasn't so much what they got wrong, as to what they didn't include. In Goodfellas, the heist was glossed over in the sense that we didn't get into all the planning and mechanics. That was because Henry Hill wasn't involved in the actual robbery and it was his story in the seminal book Wiseguy that drove the narrative. Asaro was mentioned in that book but I don't think Hill revealed much about what Asaro's actual role might have been. Hill alleged a lot about Asaro to the feds and the cops, it just didn't get into the narratives in film and books. While the film and books dealt with Paul Vario and the Lucchese crime family, the other crime groups played a role in the story, too.

What really happened to the $6 million in cash and jewels?

From the trial testimony and other sources, it appeared that Jimmy Burke kept a large chunk of the money and plowed it into a drug deal and some legitimate businesses. He may have also put some in a safe deposit box. Other participants like Asaro and Valenti appeared to get a piece of the cash. The jewels went out as tribute to other Mafia families. Some of the baubles may just have been sold off to fences.

Why do you think Vincent Asaro was found not guilty?

As I relate in the book, I think the jury had problems with Valenti's testimony. Much of what he testified about in terms of the heist had very little corroboration. It was just his word. The defense tried to exploit that. I also think that the case was just too complex, the indictment too intricate for the jury. Another thing was the courtroom dynamic. Asaro, an old man, was the only defendant in the dock. He certainly didn't look like a mob tough.

Vincent Asaro outside the Maspeth business of Bonanno crime boss Joseph Massino. Photo courtesy of US Attorney's Office, Eastern District of New York / Citadel Books

What did mob turncoats Salvatore Vitale and Gaspare Valenti testify about and what does that say about the Mafia code of silence?

With so many Mafia members and associates becoming cooperating witnesses, it is fair to say the old concept of Omerta is no longer a deterrent to people revealing the secrets. Vitale gave evidence about Asaro's position in the crime family and spoke about the alleged passing of Lufthansa jewels to Joe Massino. Valenti's testimony was the spine of the government case. He had years of close association with his cousin, Asaro, and testified about the planning and execution of the heist, as well as other crimes Asaro was charged with. The most notable was the killing and disposal of the body of hijacker Paul Katz.

How did you approach recreating the narrative of the crime and its brutal aftermath?

I had the trial testimony from the Asaro case. But I was also able to retrieve from the National Archives the testimony of the only other Lufthansa trial, that of Werner, the airport worker, who was convicted in 1979. There were also key hearings by the Senate in the years before the heist which showed the extent of airport pilfering and gave me perspective. I also had the benefit of covering the trial of former Bonanno boss Joe Massino, which helped flesh out the crime family history and Asaro's role. There were also some documents made available to me, ones that weren't widely circulated, which gave background on Henry Hill, the murder of Paul Katz, and allegations of police corruption.

Do you think Asaro's fading influence in the criminal underworld is representative of the Mafia decline?

I think, to some extent, Asaro's fate and decline is a metaphor for what has happened to many of the old Mafiosi. They spent money for today and didn't think about the future, about how the nature of crime would change. They had no plan and didn't think strategically. The bosses did well and got rich, but the captains and soldiers have nothing to show for their lives. Asaro pined for the old days, which cannot be retrieved. There is also no loyalty in the mob, as he found out from the way Valenti turned on him for his own self interest.

Since this story is so well-known in pop culture, what surprised you the most while writing the book?

From the old Congressional materials, I discovered how open the airports were to the mob, much beyond what we saw in Goodfellas. I was also surprised and disturbed to see how inept law enforcement was in going after the mob and how cops could be compromised back then. I also was surprised to see how much chance and luck played a role in the heist. It was just by chance that the information about the valuable room got to the Jimmy Burke's crew and it was sheer luck that they didn't get caught pulling off the heist. It also amazed me that, aside from Werner, nobody else got charged [until Asaro], mostly because Burke cleaned house and had people killed.

"The Big Heist" by Anthony Destefano is out now on Citadel Books — order it here.

Follow Seth Ferranti on Twitter