The United States’s sordid history with drugs haunts the country to this day, infecting much of the deep-seeded tensions regarding race and class, not to mention the country’s historically radical generation gap. In our column #TBT on THC, we parcel through the canon of American anti-weed propaganda of yesteryear — from “Reefer Madness” to “Just Say No” and D.A.R.E. — and analyze their content and context from the perspective of the present.

Some anti-drug films aim to teach you a lesson, perhaps by exploiting your empathy. Others attempt to scare you, often by fudging the data. Occasionally, you get yourself a film that can do both, and these tend to be of the “educational” variety, designed to be shown in schools to a larger student body. They more closely resemble a TV movie, often shown as after-school specials, but with the explicit intention of having moral value, of synthesizing the power of storytelling into a utilitarian tool.

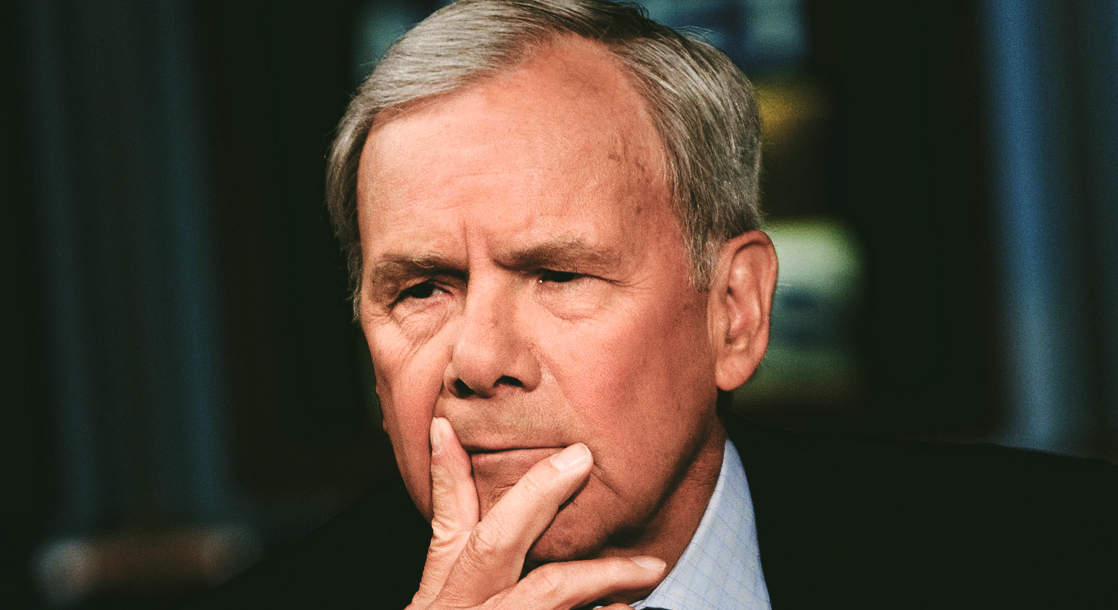

Stoned (1980) is the propaganda equivalent of an arthouse drama, starring child actor turned nightmarish Trump clown Scott Baio. When the film opens, we first see Baio’s Jack rowing a boat while his brother swims laps around him. Jack is a campus dork, dependent on his cooler older brother, Mike, to usher him into the social ecosystem. Early on, we see Jack bugging his brother on their way to school about whether they can have lunch together, with Mike sternly reminding him that come next year — once Mike is off to college — Jack will have to find a social circle of his own.

We learn that Mike is a beloved swimmer, on his way to the state championships. During a conversation around the dinner table — which alludes to Mike and Jack’s dead mom with enough casualness for me to momentarily posit that they murdered her — we see their father goading his son’s future in the Olympics, and all but ignoring Jack’s high academic marks. It is a classic case of physical attributes winning out over intellectual vigor, a dynamic that the film subverts by grounding the brothers’ relationship with genuine affection.

While Jack is succeeding in school, a failed attempt to court Felicity, his campus crush, leads the kid to his first encounter with drugs. And as is the case with most anti-drug propaganda, the moment of truth is inevitably a pretty tame affair. After a single toke under a campus tree, Jack almost instantaneously gets the munchies. Overnight, he goes from mathlete to future hacky-sack fanatic, with no sense of in-between to be found. Soon enough, Jack is stoned all the time: in class, where he once was the apple of his teacher’s eye; at home, where his brother begins to suspect something; and socially, managing to woo his crush with a newfound sensibility that she can’t quite put her fingers on. She went from finding him awkward and unappealing to goofy and light, with seemingly no idea what could be responsible for the switch.

Going in, I was prepared to eyeroll the film, largely thanks to its including one half of Joni Loves Chachi — rarely a recipe for anything but disaster. But Baio is somehow able to actually come across as a real person. How he manages to charm Felicity with literal dad riddles and a deadass pantomime is beyond me, and leads me to think that there might be a B-Plot in which the entire school is actually being pumped full of THC. Something about Baio’s stoned boyishness manages to actually make him a sympathetic character. His charm doesn’t feel forced or curated specifically as a vessel for moral telegraphing. He comes across bafflingly enough as a real person.

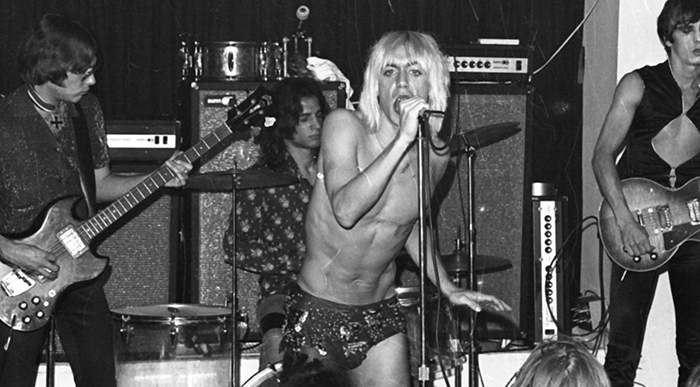

Stoned aired as part of ABC’s famous series of After-School Specials, which had an impressive 25 year run between 1972 to 1997. And, in some ways, it taps into the kind of adolescent charm that Baio displayed on Happy Days. That show was a nostalgia trip meant to quell the nerves of an older generation watching their country change before their very eyes. Going into the 1980s — Stoned aired in November of 1980 — these specials functioned much the same: a dam meant to hold back the flood of change the country was bearing witness to.

The film keeps things vague; the wisdom shared doesn’t fully amount to much. “If you just avoid your problems instead of just facing them,” Jack’s teacher, Doug, tells him, “then you’re never going to know how to deal with them.” Just what these problems are, or what that sentiment even means, remain unexplored. It might be social anxiety and isolation; living in the shadow of an older brother who made me scream “daddy!” on more than one occasion; maybe it’s a mix of all three. But what makes the film work is that it largely avoids hysterics. The effects of weed aren’t made to seem like negatives, but rather something of a performance enhancing drug. After getting into marijuana, Baio’s Jack transforms into a more confident version of himself, and finds a way to actually come into his own personhood with little-to-no anxiety.

Still, Stoned is at least intended to be an anti-drug film through and through. When Jack goes back on the water with his brother, but smokes right before, you can see where the film is going after half-an-hour foreshadowing a promising swimming career. But aside from that minor tragedy, the film’s main failure is that Baio comes out best when he takes a hit. His goofiness is unlocked, and I for one found it bizarre that someone might watch this and not be smitten by what weed could do for them. It’s a strange note for the film to leave us with: the story of someone who should have known better, but then becomes better. Even with its airing at the top of the 1980s, the film can’t fully undo the prior decade’s liberation of drug taboos. And at his worse, Baio can’t help but look like he might just end up with flowers in his hair.

Follow Rod on Twitter