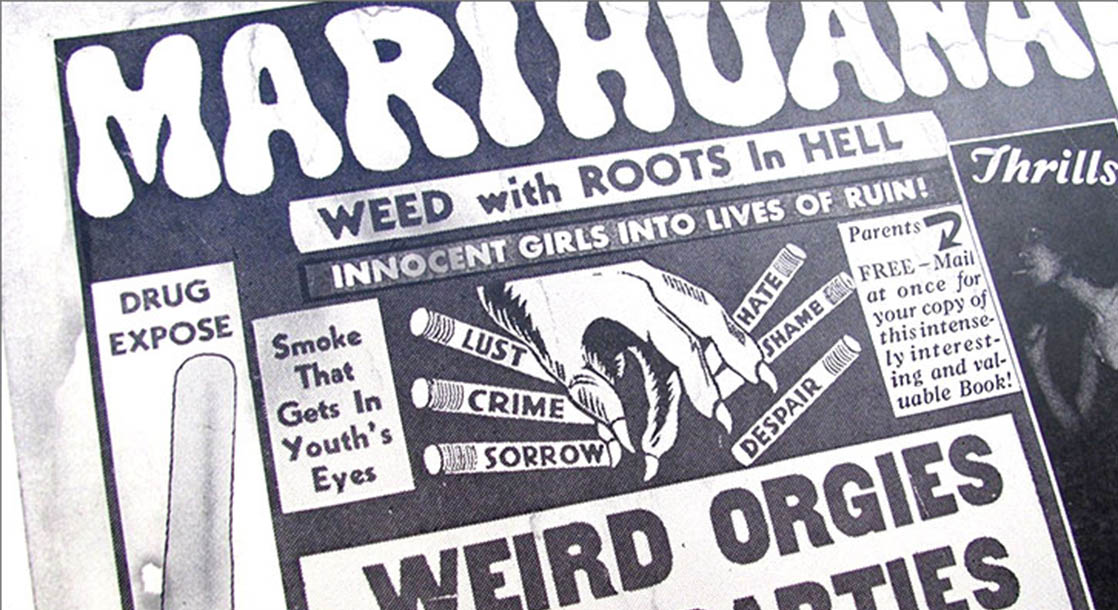

Lead image via

Why does “longform journalism” exist? The answer will not, as the outdated headline formulation states, surprise you. In fact, the answer is incredibly obvious and stupid as shit. To put it simply: Writers like writing long things, editors feel important when they edit long things, and when publications run long things, they signal to the world that they’re not just grubbing for clicks by gaming Facebook algorithms. Readers seem to like long things too, but sometimes it’s unclear whether they like actually reading it or simply posting a link to a longform piece on Facebook to prove to their friends that they read a long thing. Plus, in today’s media landscape, there’s this weird insistence that an article’s length is somehow commensurate with its quality.

But when there is a lot of a thing, that means that more good versions of the thing exist in the world. But it also means that more bad versions of the thing exist in the world, which makes it harder to separate the good things from the bad things, and effectively makes all of us collectively dumber.

The truth of the matter is that like everything else in this world, the majority of “longform journalism” is bad. Most profiles of famous people are terrible. Either the writer is a willing stooge who pretends to cut to the core of their subject’s soul while knowing good and well their entire interaction has been staged by the celebrity’s “team” to portray them in whatever light will most effectively sell the movie/album/TV show the megastar happens to be pushing; or even worse, the writer will go so far out of their way to “invert the celebrity profile” that they manage to turn what could have been a glorified––albeit artfully crafted––press release into a hacky, postmodern press release. Most true crime pieces are exploitative, because they treat the real-life pain and suffering of non-famous people as atoms to be arranged in whatever narrative the writer thinks makes a compelling story. Most investigative reports, however painstakingly sourced and fact-checked, are misleading by dint of the fact that their authors are experts in journalism and not whatever thing they’re investigating, and therefore fail to acknowledge some detail that places the entire chain of events in context. Most longform first-person pieces are bad because the types of people who write them are either self-absorbed assholes or kinda boring (often both); most fancy prestige-bait interactive web features are bad because they make your browser crash if you’ve already got more than three tabs open. There are other types of longform journalism (longform pieces on scientific phenomena, longform pieces written by old people about things young people like, longform birth certificates), and most of that stuff is bad too.

Now that I’ve exhausted nearly all of your attention span trying to convince you that longform journalism often sucks ass, I am going to say this: there is actually a wealth of truly great longform journalism out there, and some of it involves weed! Given that it’s the day after 4/20 and all sorts of people came out of the woodwork to engage in weed-related activities, it would be almost impossible to just crown a few people the Potheads of the Week and leave it at that. So instead, I decided to highlight a few of the choicest weed-related longform nugs of the past year or so for you to curl up with over the weekend. Some of these pieces––call them Potreads, Longweeds, Bongform, or whatever other weed-related journalism pun you can think of––offer empathy and insight into various cultures surrounding marijuana. Some radically reframe longstanding public policy issues surrounding the substance. And others still peel back the mechanics of the greater global drug trade to expose its convoluted and often contradictory inner workings. But they have one thing in common, and that thing is that they are all somehow at least tangentially related to pot.

Image via

"The True Story of Rastafari"

Lucy McKeon for The New York Review of Books

“Rastafari began not simply as a form of countercultural expression or fringe religious belief,” writes Lucy McKeon in her piece. “It involved a fight for justice by disenfranchised Jamaicans, peasant laborers and the urban underemployed alike, in what was then a British colony.” And while marijuana itself is closely associated with the movement due to its use as a religious sacrament, to Pinnacle––the first Rastafari community, created by Leonard Howell in the 1930s––the herb represented a path to financial independence from their colonialist oppressors. Supported by the cultivation and sale of marijuana, Pinnacle flourished in the 1940s and early 1950s, and Rastafari alongside it, but government raids on Pinnacle’s marijuana crops soon caused the community to dissipate, and the Rastafari movement itself was co-opted by the a government that once oppressed it in order to lure in tourists. Now, as Jamaica edges closer and closer to legalizing marijuana, a group of activists––led by Bob Marley’s granddaughter Donisha Predergast––are fighting to reclaim Pinnacle and re-establish a community that once stood as a symbol of cooperative living for the Jamaican people.

"Dogs on Marijuana: Not Cool"

Andy Newman for The New York Times

The title of this piece really says it all: DON’T [clap emoji] LET [clap emoji] YOUR [clap emoji] DOG [clap emoji] NEAR [clap emoji] WEED [clap emoji].

"Public Banking Goes to Pot"

Jeremy Lynbarger for High Country News

These days, public banks –– i.e., banks owned by governments instead of private companies –– aren’t really a thing. But amid growing questions about how California can further legitimize its legal weed industry, one Oakland City Councilwoman is pushing for the city to open a bank that would be able to house the cash being brought in hand over fist by the state’s cannabis industry, which privately held banks can’t touch given that marijuana is illegal on a federal level. If the plan succeeds, Oakland’s would be the first public bank to open in 98 years, and might establish a blueprint for local communities to create financial institutions catering to their particular local issues, regardless of whether or not those issues involve marijuana.

"Ebbu and the Rise and Fall of the Modern Weed Dealer"

Alex Halperin for Pando

Alex Halperin’s story about Ebbu, the failed marijuana company that strived to weld Silicon Valley precision onto the legal weed industry, is basically the opposite of Jeremy Lynbarger’s piece about public banks. Where a public bank would serve to help marijuana entrepreneurs from getting screwed, Ebbu’s cofounder Michael “Dooma” Wendschuh was a marijuana entrepreneur out to screw everyone else. He berated employees, lied to investors, and broke federal law, all in the name of creating the “Budweiser of weed”––AKA, marijuana products that’ll make you feel how the label says it’ll make you feel. Problem was, as Halperin puts it, “[Ebbu] knew far more about what they could sell than what was scientifically feasible.” Just before he could own a legal stake in Ebbu, Dooma was forced out. The piece reads like foreshadowing of how stupid and terrible the legal weed industry might be if it’s completely overtaken by sociopathic tech bros who place profit over all else.

"Buying Drugs Online: Shedding Light on the Dark Web"

The Economist

Leave it to The Economist to do a deep, data-driven dive into the drug trade on the dark web, whose vendors offer product reviews, fair-trade drugs, and nearly untraceable transactions. Turns out weed is the most popular drug on the dark market, which can feel so legit to vendors that it might just feel legal –– the report highlights one dark web weed dealer who got busted in part because he trademarked his Silk Road vendor name. An ideal journalistic chaser to The Economist’s report is “The Satoshi Affair,” Andrew O’Hagan’s profile of the man who claimed to invent Bitcoin––the chief cryptocurrency of the dark web––which ran last year in the London Review of Books. Though it clocks in at over 35,000 words, O’Hagan’s piece reads like a cross between a dissertation and a thriller, alternating twists with sober analysis in a way that elucidates the greater topic at hand while making it clear his subject is an unknowable mystery.

For more longform gems on cannabis, MERRY JANE’s editors sent these picks too:

“The Failed Promise of Legal Pot”

Tom James for The Atlantic

“El Chapo and the Secret History of the Heroin Crisis”

Don Winslow for Esquire

"Queens of the Stoned Age"

Suketu Mehta for GQ

"The Big Smoke"

Brett Popplewell for The Walrus

“The Rise and Fall of Wrestling's Weed-Dealing, Cat-Breeding Phenom”

Omar Mouallem for Rolling Stone