Image via

[Author’s note: Terminology for the world’s oldest profession has changed since Margo St. James’ heyday. Modern-day advocates eschew terms such as “prostitute,” and prefer to use “full-service sex worker.”]

It was 1997, and Margo St. James, the iconic sex worker activist, was tired of hearing “No.” She sat down to write a poem about it for the San Francisco Chronicle.

“No to litter, no to trash. / No to women getting any cash. / No to smoking, no to toking. / No money to mothers who are coking … How long will the law’s arm reach? / An expensive way to preach. / Isn’t it better to simply teach?”

St. James, who was 83-years-old when she died on January 11, left an indelible mark on the global sex workers’ movement. She assembled a unique coalition of her fellow sex workers, politicians, lawyers, and even cops to power the political campaigns of Call Off Your Tired Ethics (COYOTE), a seminal group founded by St. James that links sex workers with counseling and legal aid. She organized San Francisco’s annual Hookers’ Ball, where strippers, elected officials, and celebrities partied for sex workers’ rights. She took her activism international when she hosted the World Whore’s Congress — a three-day conclave to promote and educate on HIV/AIDS protection for sex workers that also birthed the World Charter for Prostitutes’ Rights — in Brussels’ European Parliament in 1986.

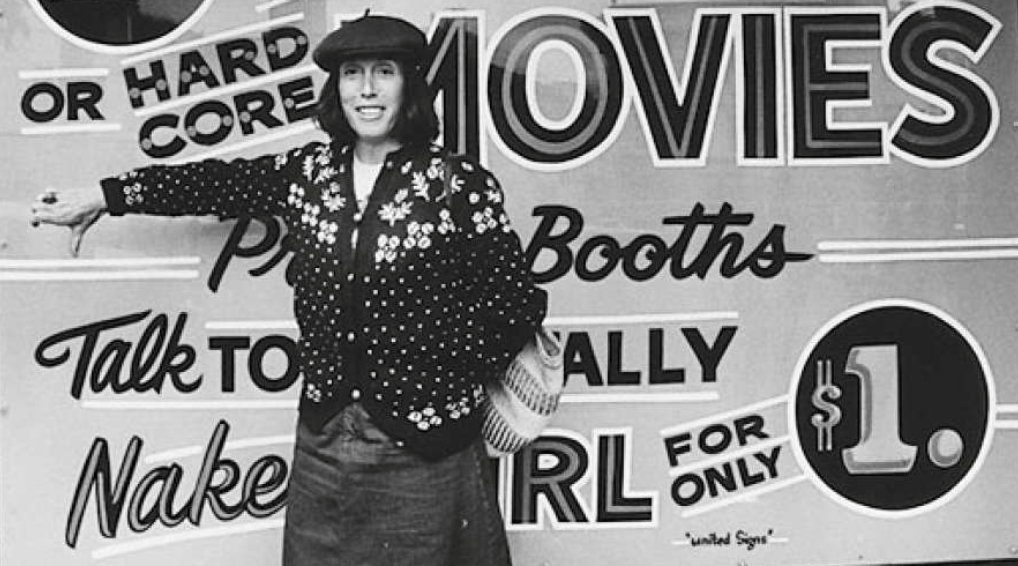

Margo St. James [center, in black beret] at the 1985 World Whores Congress in Amsterdam. Photo by Annie Sprinkle

She is lauded for fighting against sex worker police abuse and advocating for STD/STI education. But people often forget that St. James’ legacy also includes pushing for the decriminalizing drugs. She was against all tools used by police to target oppressed groups.

St. James grew up on her father’s dairy farm in Bellingham, Washington. By 1958, she was 21-years-old and moved to San Francisco with aspirations of becoming an artist. Little did she know she’d eventually become a leading figure in the crusade for sex work decriminalization by 1973, the year she founded COYOTE.

She settled in San Francisco one year before drag queens and queer sex workers led the pastry-fueled Cooper Do-Nuts Riot in Los Angeles. That night, abusive cops showed up at the 24-hour doughnut cafe to determine whether customers’ appearances matched the gender shown on their government ID. Restaurant patrons pelted LAPD with doughnuts until they were forced to retreat. This rebellion shows that some sex workers and their allies were already fed up with brutish police tactics heading into the 1960s.

Indeed, the decade was characterized by the acceleration of various social movements in California, many of which inevitably intersected, as they were fighting against the same, punitive law enforcement rackets. As a result, some activists from other arenas — specifically from the Bay Area’s momentous cannabis legalization movement — recognized the parallel struggles of sex workers, motivating them to build strong networks and cross-amplify their missions.

Today, the link between sex work and drug decriminalization — not to mention BIPOC and LGBTQ rights and those of other vulnerable populations — is recognized by many. “Any analysis of the drug war that fails to center the impact on sex workers would be very incomplete,” writes Jessica Martínez, a methamphetamine services specialist at Washington DC’s Honoring Individual Power and Strength (HIPS). The organization supplies employment, housing, and harm reduction resources to individuals impacted by both Drug War and sex work policing.

Racial justice group Movement 4 Black Lives has linked these issues in its official platform. “Both the Drug War and prostitution enforcement divert millions of dollars away from meeting the needs of people with substance dependence and people in the drug and sex trades, including non-coercive, accessible, and evidence-based treatment, housing, health care, education, and living-wage employment,” the organization’s official policy platform states.

Margo (left) at 1995 Hookers Ball with Kat SunLove. Photo by Layne Winklebleck

The activist scene St. James was a part of neatly illustrated the power of intersectionality in tackling issues involving rights, abuse, and visibility. “Harvey [Milk] was doing the gays, Margo was doing sex, and we were doing marijuana,” recalls Michelle Aldrich, a longtime cannabis activist and a co-recipient of High Times’ Lester Grinspoon Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011. She also helped edit the first edition of Jack Herer’s The Emperor Wears No Clothes in 1985.

Michelle Aldrich met St. James in the 1970s. Later, her husband Michael Aldrich joined the Exotic Dancers Alliance board, a strippers’ justice group. He’s still the sole man serving on its advisory committee today. “All the politics that were going on — it was like, we were supposed to know each other,” says Michelle, who also helped St. James organize the Hookers’ Ball.

St. James was also close with Dennis Peron, the legendary cannabis activist who led the charge on Prop. 215, the legislation that made California the first state to legalize medical marijuana in 1996. They helped amplify each others’ political aims. Oh, and Peron supplied St. James with a ton of weed.

COYOTE organizer Lottie Da remembers going to Peron’s Cannabis Buyers’ Club at 1444 Market Street with St. James in the 1990s. “They said, ‘You’d never get in if you weren’t with Margo,’” she laughs. “I said, ‘That’s OK.'”

Michelle recalls that even Harvey Milk attended activist meetings in St. James’ North Bay home. She says that strategy was discussed for “no longer than five minutes. Then we’d all get in the hot tub and smoke dope.”

Photo courtesy of Molly Bode

St. James and Michelle also served on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors’ Drug Abuse Advisory board in the ‘90s. When St. James left, she was replaced by local trans activist Victoria Schneider, who in 1996 was picked up by SFPD on prostitution charges, and strip-searched to supposedly determine her gender. Schneider famously sued the city and county of San Francisco and won her case.

“It’s sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll, that’s how it is,” says Schneider when asked about the intersections of sex work and drug activism. “It’s part of our culture.”

Schneider recalls a time the now-deceased activist accompanied her to a trial in which Schneider’s sex work charges were thankfully dropped — and the two were able to recoup the cannabis the cops had confiscated from Schneider in the arrest. “Margo just liked to smoke weed,” Schneider says. “She was a good one at that. Everyone knew that she smoked it.”

At St. James Infirmary, the for-and-by-sex-workers health clinic in SF’s Tenderloin District, the drug-sex connection made visible by Margo, or the “patron saint of sex work,” continues to influence those who advocate for the health center today.

“Rather than adopt harm reduction principles, and recognize that individuals are engaged in drug use and/or sex work for myriad reasons, governments prefer to focus on abatement and enforcement activities, which have long since been proven to be archaic and ineffective,” says Johanna Breyer, St. James Infirmary’s founding executive director and co-founder of the Exotic Dancers Alliance. She also points out that the policing of drugs and sex work disproportionately affects people of color and transgender women.

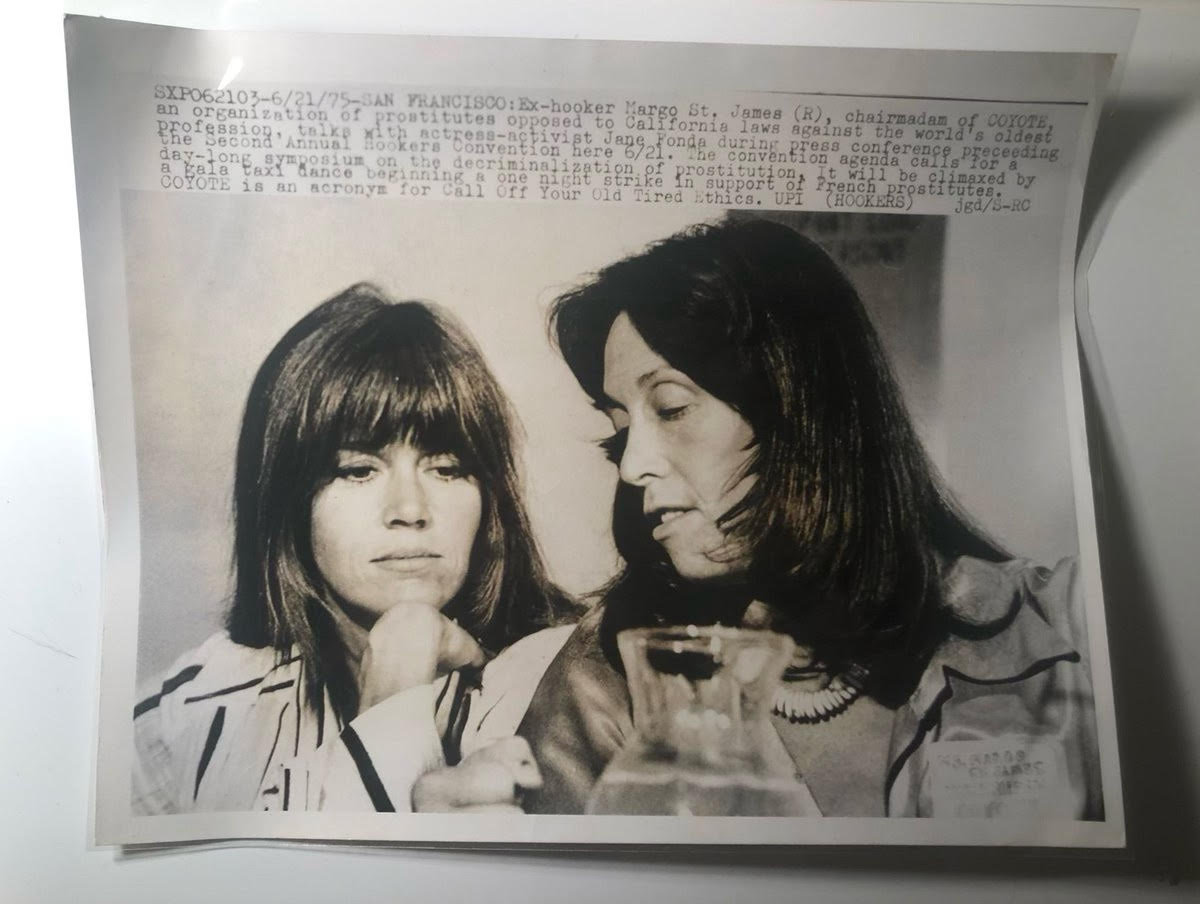

Margo on Right. Photo courtesy of Johanna Breyer

Cannabis decriminalization aside, there hasn’t been enough movement towards the official adoption of harm reduction strategies for dealing with addiction in the years since St. James raised hell. Certainly, the US has fallen behind the global curve in regards to decriminalizing sex work.

“One could argue moral superiority, antiquated religious beliefs, public health ignorance, or simply lack of compassion and understanding have allowed dominant policies ignoring body autonomy to exist,” Breyer says. “Yet, here we are.”

Donate to Honoring Individual Power and Strength (HIPS), a non-profit organization that offers harm reduction services to people impacted by the Drug War and sex work policing.

You can also donate to St. James Infirmary by clicking here.