Debates about "greatest albums of all time" invariably start in the '60s, the decade in which long-playing records overtook 7" singles as the most common format in popular music. These best lists consistently name-drop two albums: The Beach Boys' Pet Sounds and The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. This makes perfect sense. The two monumental psychedelic pop albums were inextricably linked, as Pet Sounds was primarily inspired by The Beatles' previous album, Rubber Soul, and Sgt. Pepper's by Pet Sounds. Even Rolling Stone — the cradle of brawny, bullheaded rockism — ranked the two not-very-testosteroney pop albums #1 and #2 on its "500 Greatest Albums of All Time" list.

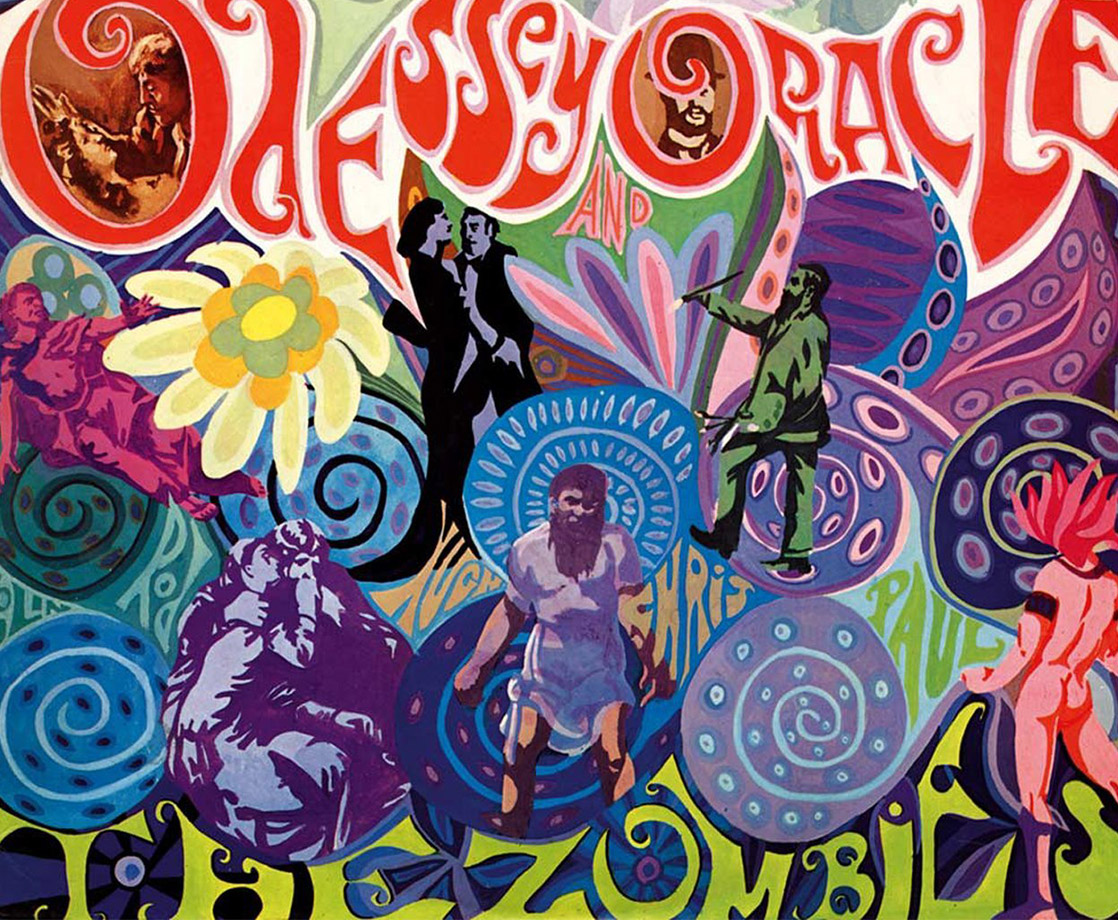

But remove the narratives, the creative tug-of-war between Brian Wilson and Lennon/McCartney, the attention-grabbing songs about LSD, the Beatlemania, the media craze, and put 50 years in the rearview, and there's now stiffer competition for the title of Best '60s Psychedelic Pop Album, let alone Best Album of All Time. Look at The Kinks' Face To Face, Harry Nilsson's Aerial Ballet, Caetano Veloso's self-titled 1968 album, Van Dyke Parks' Song Cycle, or Love's Forever Changes — all rich albums that, for some reason or another, never got due credit at the time of their releases. But the one album that faced the steepest uphill battle for its release and promotion, and most closely rivaled Wilson and McCartney's classicist pop bonafides, was The Zombies' Odessey and Oracle, released 50 years ago this month.

Nobody got chewed up and spat out by the commercial gold rush of the British Invasion like The Zombies, a five-piece from the North London suburb St. Albans. Their mid-'60s rise to fame mirrored that of any other British group from the era: release a hit single ("She's Not There," a top-20 hit in the UK and US in 1964), tour the U.S., perform on an American television show (Hullaballoo, see below), and at the behest of their record label, populate their debut album (1965's Begin Here) with 50% original compositions and 50% pepped-up white boy covers of American R&B songs. The band began to record a follow-up, but with Begin Here failing to chart, Decca Records dropped them like yesterday's bell-bottoms.

Thus began a period of uncertainty for The Zombies. They embarked on a disastrous ten-date tour in the Philippines in 1966, for which each member would receive around 18 pounds per show, according to bassist/songwriter Chris White in a recent oral history. After that trip, which was also marred by civil unrest in the country, the band fired their agent, and returned home to find that their manager had quit. Somehow, The Zombies then secured a one-album deal with CBS, who assessed the band's commercial woes by granting them a paltry advance of 1,000 pounds (for comparison, Sgt. Pepper's estimated recording cost was 25,000 pounds). "That was just for the mono mix," White explained, "Rod [Argent, the band's keyboardist and other primary songwriter] and I had to pay 1,000 pounds ourselves to mix it in stereo!"

The band made the best of it though, securing sessions at Abbey Road Studios in mid-1967 just after The Beatles finished Sgt. Pepper's, and even using Lennon's iconic mellotron without his permission. Because of their budget, the band had to be impeccably rehearsed before hitting the studio for tightly-monitored three hour sessions, and when they finished recording what would become Odessey and Oracle, there were no outtakes or unused songs. It was literally all they could afford to record.

The album's pre-release singles tanked in late 1967, and CBS boss Clive Davis decided to shelve the album. After a December performance in England, The Zombies decided to break up. "We just said, 'We can't afford this,'" said White, citing the self-funded stereo mixing. Enter famed pianist and recently-hired CBS A&R Al Kooper, the hero of this story. Allegedly, he loved the Odessey singles so much that he persuaded Davis to change his mind. "It was only due to his enthusiasm that the album was ever released," said singer Colin Blunstone in a 2013 interview.

Almost a year after the band first entered Abbey Road, Odessey and Oracle, accidentally-misspelled title and all, was finally released in the UK on April 19th, 1968, and in the U.S. a week later. Like its previously-released UK singles, it flopped. "It got great reviews," Argent said in the oral history, "but it didn't sell." The American label tried out two more singles; those flopped as well. The third and final try, a song called "Time of the Season," seemed well on its way to a similar fate until early 1969, over a year after The Zombies' breakup. In the oral history, drummer Hugh Grundy recalled the song's miraculous commercial reanimation:

Three times they mail-shot "Time of the Season" to the radio stations. They kept on trying. It started out in one tiny little city right in the middle of the country — Boise, Idaho. Other radio stations were listening — they must listen to each other and think, "What's he playing that I'm not playing?" They kept hearing it and going, "Maybe we better play it." And then bang, bang, bang. Then people started buying it, which is fantastic, otherwise I don't think we'd be sitting here now.

"Time of the Season" peaked at #3 on the Billboard Hot 100 in March 1969, by which point White and Argent had formed a new band and the other Zombies had found work entirely outside of music. "There had been so little interest in the band at the end that we didn't have a choice but to get jobs," Blunstone, who worked briefly as an insurance salesman, said in his 2013 interview. As evidenced by the multiple imposter acts that popped up in 1969 — a fascinating story unto itself, uncovered by Buzzfeed a few years ago — there was enough interest in the U.S. that the band could've secured a much more lucrative deal for a follow-up album. But as it stood, with The Zombies broken up, details on the band were so scarce that the promoter for the "American Zombies" could make spurious claims about members being deceased. According to Buzzfeed, when Rolling Stone contacted said promoter in December 1969, "he claimed that the 'American Zombies' formed after 'the lead singer of the Zombies was killed, and two other guys left.'" [Editor's note: Colin Blunstone is alive and well]

Every imaginable odd was stacked against Odessey and Oracle, but as every optimistic listener always hopes will be the case, good music prevailed. In this instance, the only crucial arbiters of taste seem to have been Al Kooper and an unknown DJ in Boise, but in the years between "Time of the Season" hitting #3 and today, more and more cultural gatekeepers sung the album's praises. As Blunstone put in the oral history:

Nothing happened for about eight years, but then gradually it started picking up incredible reviews and huge artists started to cite it as an influence; in particular in the UK, Paul Weller. It just started to sell like eight or nine years after it was released.

Weller, the frontman of The Jam, called Odessey and Oracle his "all-time favorite" after hearing it in the mid-70s, which increased curiosity among British listeners after his band blew up. Tom Petty loved it so much that he wrote the introduction for 2016 coffee table book The "Odessey": The Zombies in Words and Images. Other prominent rock stars including, but not limited to, Robert Plant, Dave Grohl, and Robin Pecknold have cited the album as an influence, bringing their wildly varied fanbases into the fold.

That explains the demand, and as original presses of the album soon went out of print, the subsequent supply came courtesy of reissue campaigns that have popped up like clockwork periodically through the years, first in the late '80s, then the late '90s, and most recently in the early 2010s. Accompanying these have been European and U.S. reunion tours for the album's 40th and 50th anniversaries. Like another album mentioned in the intro of this article, Love's Forever Changes, Odessey and Oracle has ascended to a status among younger generations that it never reached with baby boomers.

Looking back, Odessey and Oracle epitomizes the mid-to-late '60s era of pop culture awakening just as powerfully as Pet Sounds and Sgt. Pepper's, and contains just as much inventive merging of classical, early 20th century pop, and psychedelic rock sounds. What truly made The Zombies special was their ability to convey widely varied moods and focus on obscure themes without getting overambitious or spreading themselves thin. Odessey and Oracle effortlessly swerves between wide-eyed optimism on tracks like "I Want Her She Wants Me" and "This Will Be Our Year," and downcast melancholia on "A Rose For Emily" and "Brief Candles," all feeling of a holistic piece rather than scattered twentysomething journal entries. By making one of the album's purest love songs a letter to an incarcerated woman ("Care of Cell 44"), couching its haunting anti-war shanty ("Butcher's Tale") in World War I themes, rather than Vietnam, the band ensured they were creating something timeless, beyond their peers' gimmicky entreaties about going to San Francisco wearing flowers in your hair or tying yellow ribbons 'round ole oak trees. Couple that with clarion pop sensibility that encompassed Blunstone's almost-too-perfect tenor, vocal harmonies that border on monastic, just the right amount of trippiness, and that blessed invention, the mellotron, and you've got a classic. Odessey and Oracle is time-stamped in its amber-encased '60s charm, but timeless in its pure pop genius.

Contemplating whether The Beach Boys and Beatles' respective canonical classics would have fared the same with similarly dire origin stories is a big, dumb game of "What if?", but suffice it to say that Odessey and Oracle deserves to be constantly in conversation with those two albums. After all, The Zombies thought it would be. I'll leave you with one final excerpt from the oral history that sums up the fertile creative atmosphere of the psychedelic pop era:

ARGENT: We didn't think, 'Oh, we have to do something like 'Pet Sounds,' but I think it did inspire us. There wasn't any attempt to copy the elements that were in there so much as the creativity of it and the feeling of pushing pop music forward into different spaces than it had been before. I think 'Pet Sounds' was an indirect influence, as it was on 'Sgt. Pepper.' Since then, Paul McCartney's said the same thing; they felt they had to do something similar.

WHITE: There was a lovely challenge from Brian Wilson and The Beatles — "Pet Sounds," "Sgt. Pepper," and all that sort of thing. That was an exciting period of trying new things.

Follow Patrick Lyons on Twitter.