Image via

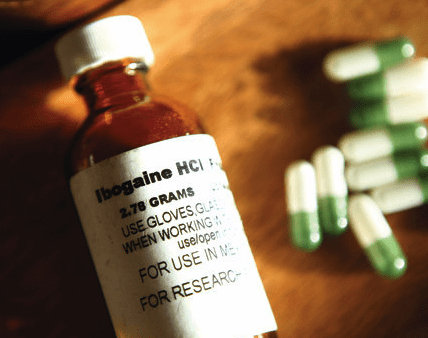

Researchers have developed a new experimental compound that may be able to provide the stress-relieving properties of ibogaine without the toxic or hallucinogenic side effects.

Ibogaine is a psychedelic alkaloid that naturally grows in a variety of plants native to West Central Africa in a tiny country called Gabon. Local tribes have been using Iboga for medicinal and spiritual purposes for centuries, but in recent years, a growing number of Westerners have discovered the healing potential of this powerful psychedelic. Most notably, ibogaine has shown incredible promise at helping people break long-term addictions to heroin, alcohol, or other drugs.

Much like ayahuasca or peyote, ibogaine is usually consumed at clinics or retreats under the supervision of counselors or therapists. In a controlled setting, ibogaine users often find that they can confront their deepest fears, anxieties, and traumas, helping them overcome addictive behaviors. Unfortunately, this compound can cause heart arrhythmias, which can be deadly to people with underlying heart conditions.

Most researchers investigating the therapeutic use of psychedelics have avoided ibogaine due to these potential health risks, but David Olson and a team of researchers from UC Davis found a way to harness the medical potential of this medicinal plant. Olson and his team created a new experimental compound called tabernanthalog (TBG), a synthetic analog of ibogaine that seems to be free of hallucinogenic or toxic side effects.

Scientists from UC Davis, UC Santa Cruz, and the University of Stanford launched a new animal study to determine if this new drug can safely treat stress and anxiety. For the trial, researchers administered a 10mg/kg dose of TBG to mice, exposed them to unpredictable mild stress (UMS), and then conducted a number of behavioral and physiological tests.

This new study, which was recently published in the Molecular Psychiatry journal, reports that one single dose of TBG effectively “combats the detrimental effects of stress.” This experimental medicine quickly reversed many of the negative effects of stress, including anxiety, cognitive inflexibility, and reduced sensory processing.

“It was very surprising that a single treatment with a low dose had such dramatic effects within a day,” said co-author Yi Zuo, professor of molecular, cell, and developmental biology at UC Santa Cruz, in a statement. “Amazingly, TBG reversed all of the effects of stress… I had a hard time believing it even when I saw the initial data.”

The study authors are hopeful that tabernanthalog can be developed into a new medicine that can provide the health benefits of ibogaine without posing the same heart health risks. The study notes that the mice did not seem to be tripping out after being dosed with TBG, but cautioned that “only human clinical studies can ultimately confirm that it is non-hallucinogenic.”

The study goes on to explain that “prolonged stress may overwhelm the capacity of the adaptive mechanisms,” overloading the brain’s capacity to process information and “predisposing the individual to diseases, particularly mental illnesses.” Animal research studies have found that chronic stress and depression can reduce the size and strength of dendritic spines, small protrusions on nerve cells that aid in the transmission of data between neurons.

Researchers found that dendritic spines in the rodents’ brains began regrowing within 24 hours after receiving one dose of TBG. The authors explain that “the newly formed spines partially compensate for the spines lost during UMS,” allowing for the creation of new synapses and the reorganization of neural circuits.

Just last week, a team of researchers from Yale University published a study reporting that psilocybin can also promote the regrowth of dendritic spines, and other studies have found that ketamine has a similar restorative effect on these spines. This exciting new field of research suggests that different psychedelics can provide similar therapeutic effects by promoting neural regrowth and boosting neuroplasticity.