British researchers are currently wrapping up the first phase of a clinical trial aimed at determining whether MDMA-assisted psychotherapy can help alcoholics remain sober.

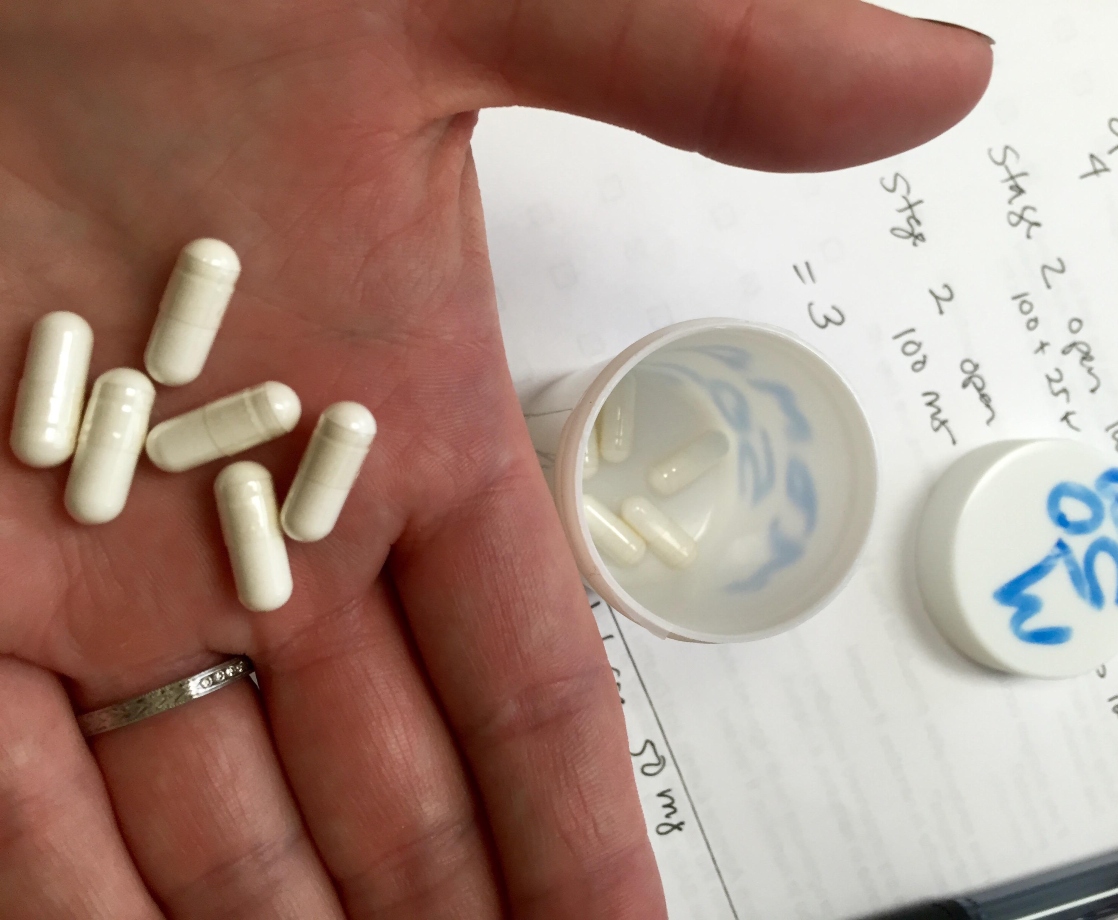

In this preliminary study, eleven alcoholics attended an eight-week course of psychotherapy. During the third and sixth weeks, recipients were given strong doses of MDMA and asked to spend eight hours relaxing while wearing eyeshades and headphones under doctors’ supervision. Following this course of therapy, doctors followed up with each patient for nine months to determine whether or not they had started drinking again.

Dr. Ben Sessa, addiction psychiatrist, senior research fellow at Imperial College London, and lead researcher of the study, told The Guardian that out of all 11 participants, “we’ve got one person who has completely relapsed, back to previous drinking levels, we have five people who are completely dry and we have four or five who have had one or two drinks but wouldn’t reach the diagnosis of alcohol use disorder.”

In contrast, around 80 percent of all alcoholics in the UK relapse within three years of completing traditional rehab programs.

Dr. Sessa explained that most addiction stems from underlying childhood trauma, but the effects of MDMA can help individuals process these repressed emotions. “MDMA selectively impairs the fear response,” he said. “It allows recall of painful memories without being overwhelmed. MDMA psychotherapy gives you the opportunity to tackle rigidly held personal narratives that are based in early trauma. It’s the perfect drug for trauma-focused psychotherapy.”

This preliminary trial is the first step in a multi-step study that aims to prove the therapeutic potential of this former party drug. This first phase was intended to show that MDMA could safely be used to treat patients without adverse side effects. Doctors monitored each patient on a daily basis for one week following each MDMA dose to ensure that patients were not suffering from depression or other side effects after receiving the medicine.

Gallery — A History of Musicians and MDMA:

Many clubgoers have reported feeling depressed after using MDMA recreationally, but the participants in this study reported that their outlook remained positive after each dose. “There is no black Monday, blue Tuesday, or whatever ravers call it,” Dr. Sessa said, referring to recreational users’ reports of depression. “In my opinion, that is an artifact of raving. It’s not about MDMA.”

Although the results are promising, the study’s small size and lack of control group prevent the researchers from officially concluding that MDMA can help alcoholics abstain. The current study does establish that the drug can be safely used in a therapeutic setting, which will allow researchers to advance to the second stage of the trial. In this stage, doctors will conduct a larger study in which alcoholics will either be given MDMA or a placebo, allowing them to conclusively determine whether this treatment is effective.

For reference, MDMA was legally used as an adjunct to psychotherapy in the US from the 1970s until 1985, and in Switzerland until 1993. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, MDMA became a popular recreational drug, often known as ecstasy or molly, and world leaders responded by banning the drug entirely.

In recent years, researchers have regained interest in the therapeutic use of MDMA. Recent studies have found that as few as two doses of MDMA can erase the symptoms of PTSD, and MDMA-assisted psychotherapy clinics are opening across the US next year.

Prohibitionists continue to argue that MDMA is too dangerous to be used medicinally, but Dr. Sessa told The Guardian that “scientists know it’s not dangerous.” The doctor points out that popular media outlets continue to classify ecstasy as “dangerous because the tiny number of fatalities that occur every year all get on their front page,” but research studies like this prove that MDMA can be safely tolerated in clinical settings.