Although drug policy reform advocates are concerned that U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions plans to implement policies that will affect the average dope user, his goal is not “to fill prisons with low-level drug offenders,” says U.S. deputy attorney general Rod Rosenstein.

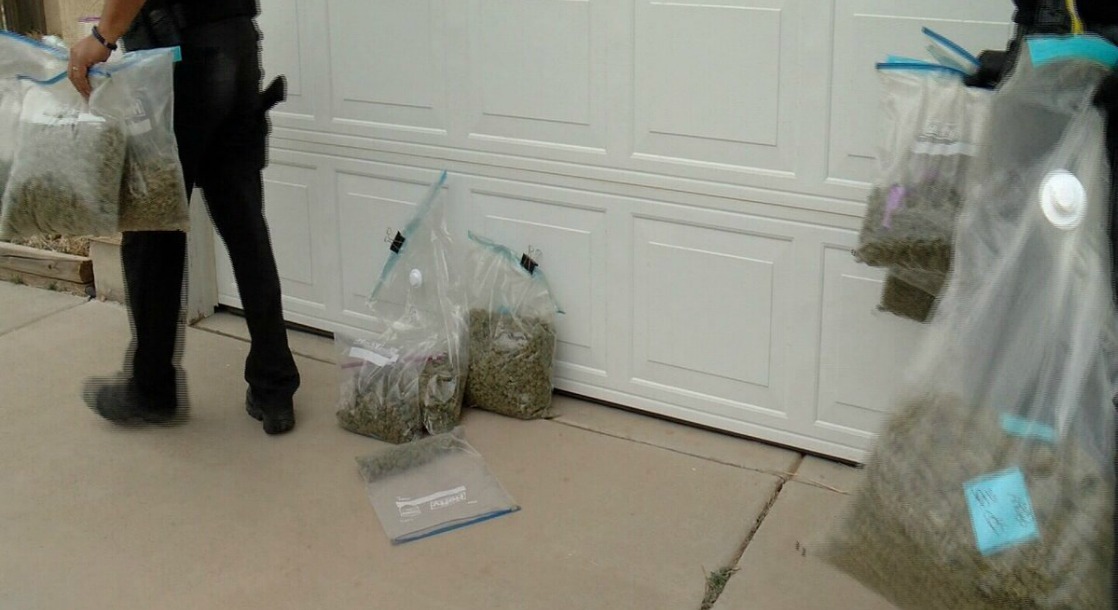

In a recent op-ed in the San Francisco Chronicle, Rosenstein writes that AG Sessions’ recently revised policy directing federal prosecutors to go for the maximum penalty in drug-related cases is a serious attempt to reduce crime in the United States. The goal of the plans, he claims, is to put a tighter leash on criminals that managed to escape lengthy jail sentences during the Obama administration.

“During that time, unless cases satisfied criteria set by the attorney general, prosecutors were required to understate the quantity of drugs distributed by dealers and refrain from seeking sentence enhancements for repeat offenders. Beneficiaries of that policy were not obligated to accept responsibility or cooperate with authorities,” he wrote.

The man responsible for the federal government’s more reasonable approach to dealing with drug offenders, former AG Eric Holder, emerged back in May to offer his disdain for how Sessions plans to take the wheel on this issue.

"The policy…is not tough on crime. It is dumb on crime," Holder said in a statement. "It is an ideologically motivated, cookie-cutter approach that has only been proven to generate unfairly long sentences that are often applied indiscriminately and do little to achieve long-term public safety."

In addition to causing an increase in crime, Rosenstein believes the Obama administration’s cavalier manners of dealing with drug offenders has contributed to a surge in overdose deaths and a supposed spike in gang-related activity.

It is for this reason, he says, that tougher policies are necessary to begin to remedy the situation.

“Officials in many cities are calling on federal prosecutors for help, and tough sentences are one of federal law enforcement’s most important tools,” he wrote. “Used wisely, federal charges with stiff penalties enable U.S. attorneys to secure the cooperation of gang members, remove repeat offenders from the community and deter other criminals from taking their places.

“In order to dismantle drug gangs that foment violence, federal authorities often pursue readily provable charges of drug distribution and conspiracy that carry stiff penalties. Lengthy sentences also yield collateral benefits,” he continued. “Many drug defendants have information about other criminals responsible for shootings and killings. The prospect of a substantial sentence reduction persuades many criminals to disregard the “no snitching” culture and help police catch other violent offenders.

In conclusion, Rosenstein said the updated policy would not cause trouble for small time drug offenders.

“Minor drug offenders rarely face federal prosecution, and offenders without serious criminal records usually can avoid mandatory penalties by truthfully identifying their co-conspirators,” he wrote.

Incidentally, there is no evidence that crime rates have flown off the chain since Holder relaxed the policy for some drug offenders. In fact, “violent crime rates are still at historic lows,” wrote former deputy attorney general Sally Yates in a recent op-ed for the Washington Post.

“There is also no evidence that the increase in violent crime some cities have experienced is the result of drug offenders not serving enough time in prison,” she added.