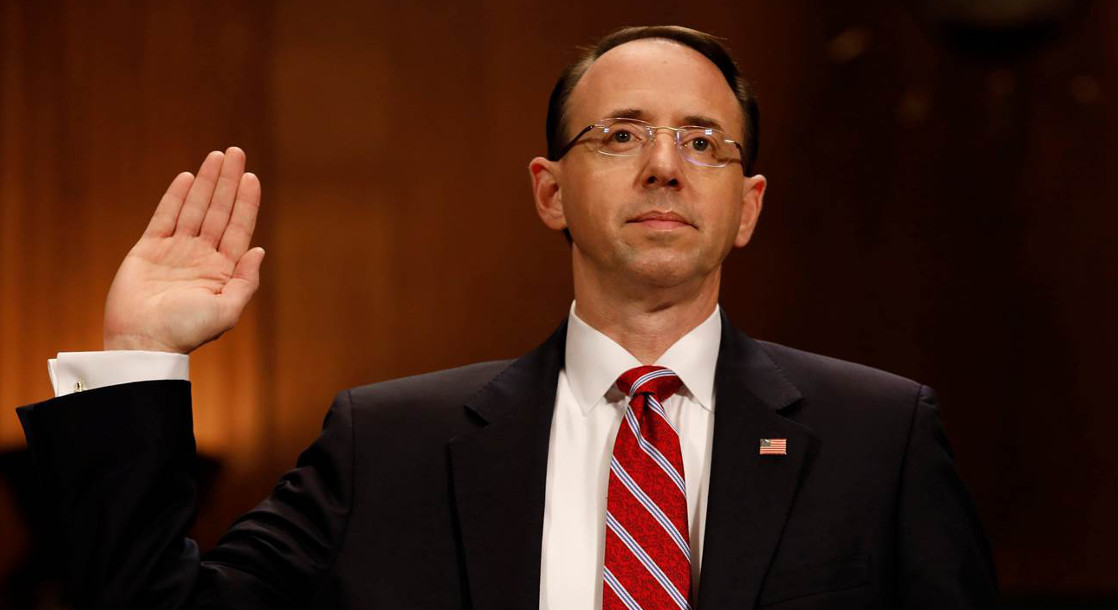

Although the U.S. Department of Justice recently announced plans to go for drug offenders’ jugulars, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein says the federal government’s new plan of attack is not intended to provide a second wind to the drug war. Instead, he insists the goal of the DOJ’s latest initiative is to simply take down the most violent offenders and other undesirables associated with the black market of illicit substances.

“We’re not about filling prisons,” Rosenstein said in an interview with The Associated Press. “The mission is to reduce violent crime and drug abuse, and this helps us do that.”

It was just weeks ago that U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a memo asking federal prosecutors to seek maximum sentences for drug-related offenses. This updated policy goes against the grain of an Obama-era memo, which urged prosecutors to take it easier on non-violent drug offenders.

Rosenstein, who was part of the more lenient approach spearheaded by former Attorney General Eric Holder, says a stricter policy is now needed because the violence associated with organized drug rings has become a more serious problem in the United States.

There is some belief among the drug reform community that the DOJ’s new approach will lead to addicts and other non-violent drug offenders, especially minority groups, being used to fill prisons = across America. However, Rosenstein affirmed that minor drug offenders, like those people busted for simple marijuana possession, are dealt with at the state level, while enforcers in Washington D.C are more interested in larger cases. He admits, though, that, in some situations, federal prosecutors do target people for simple possession in order to inflict damage to criminal operations.

The National Association of Assistant United States Attorneys (NAAUSA) supported Rosenstein’s comments earlier last week.

"We at the federal level don't prosecute 'low-level drug offenders,'" said NAAUSA Treasurer Steve Wasserman. "We don't prosecute users. Less than 1 percent of the federal prison population consists of inmates who are serving sentences for simple possession, and in almost every one of those cases, those individuals are couriers that plead down to a simple possession charge from a trafficking offense."

One of the problems with the DOJ’s latest policy that nobody is addressing is that it could lead to members of the legal cannabis trade being jammed up by the federal government’s mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines. As it stands, anyone convicted of holding 100 kilograms of marijuana (or 100 cannabis plants) goes to prison for at least five years. The only way this can be avoided is if a U.S. prosecutor agrees to have the case tried in a state court. Otherwise, a plea deal, even for first time, non-violent offenders, is unattainable. Therefore, if a federal crackdown does come down the pike, as the Trump administration has hinted it might for the past few months, it is conceivable that we could see a surge of people tied to the cannabis industry prosecuted in federal court. Right now, there is no concrete policy in place to protect anyone engaged in the cultivation and sale of recreational marijuana in states where it is legal.

Under federal law, the entire scope of the cannabis industry is really no different than cartel activity, and this reality could cause serious trouble for the industry if the Trump administration does decide to make changes to another Obama-era memo allowing states to experiment with legalization. Attorney General Sessions is expected to give more consideration to this issue next month when his task force submits recommendations pertaining to existing federal policies, including those on legal marijuana.

It is important to point out that majority of marijuana-related “crimes” in the United States are for simple possession. The latest data from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) shows that 88 percent of the 8.2 million marijuana arrests that took place between 2001 and 2010 were simple possession.