All photos courtesy of Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

Fugitives have been a part of the American consciousness since the advent of the criminal justice system. Pop culture has always romanticized the idea of the outlaw on the run, as seen in everything from movies like The Fugitive and Catch Me If You Can, to press coverage of El Chapo’s many escapes. The same goes for real-life criminals, such as Depression-era mobsters like John Dillinger, mid-century gangster like Whitey Bulger, and more. Fugitives have always held the public’s imagination. After all, we still talk about Billy the Kid and the Wild West.

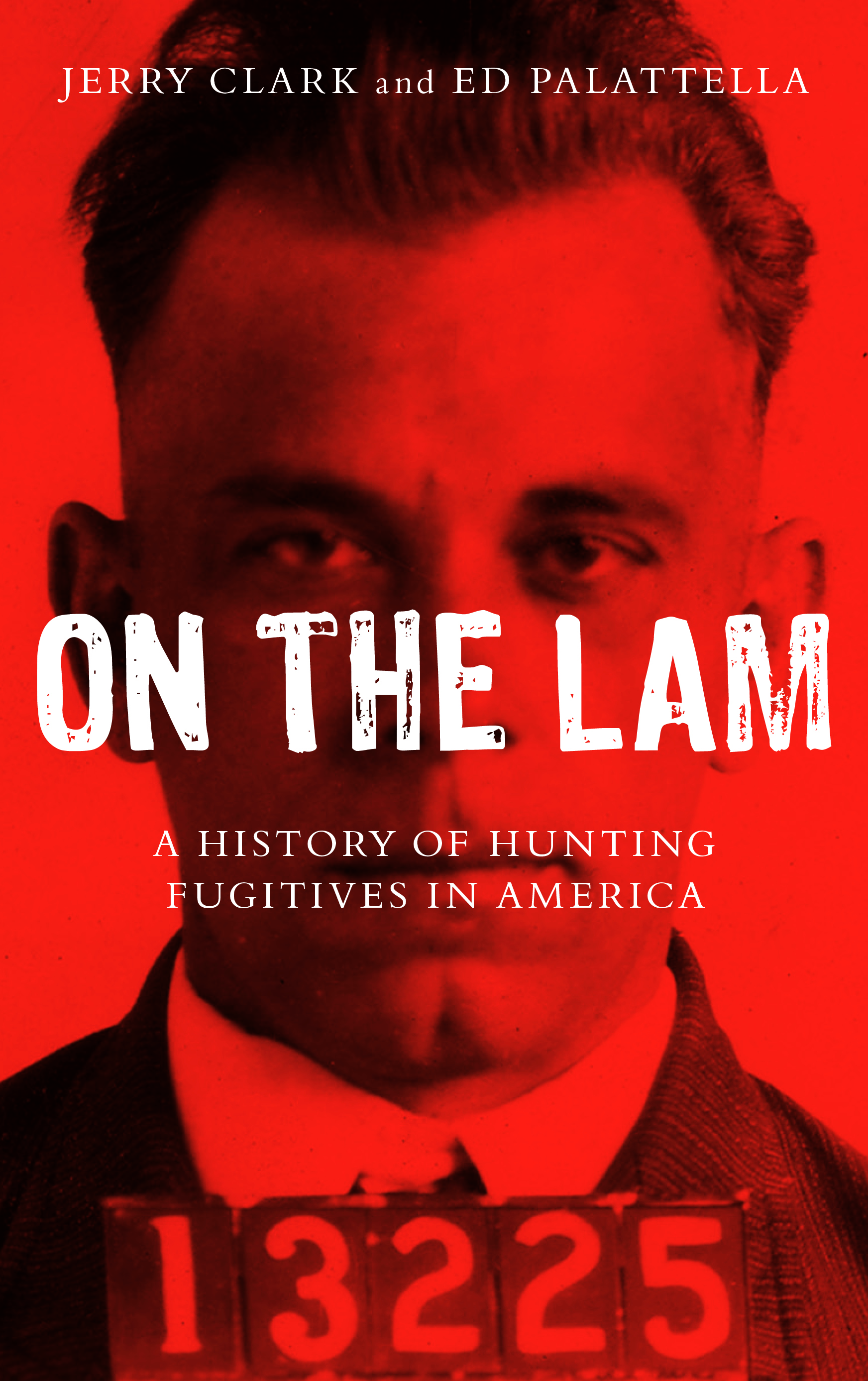

A new book, On the Lam: A History of Hunting Fugitives in America, by Jerry Clark and Ed Palattella (who MERRY JANE previously interviewed about female serial killers), looks at the history of fugitives and bail. The authors trace it from as far back as Ancient Rome, before diving into the creation of the US Marshals and the FBI. With chapters like “Infamous and Elusive,” which details the development of the Top 10 Most Wanted List, and “A Mind at Unrest,” which looks at the mental stress that plagues fugitives, the book is as immersive as an episode on The History Channel. And Clark writes from experience, too: he served as an FBI special agent for years, and helped run a fugitive task force in Ohio.

MERRY JANE talked to the authors to find out why they decided to write a book about fugitives, what sort of research they conducted, and why the concept of the outlaw became ingrained in popular culture. As Clark explains, “The United States originated as a nation of rebels and revolutionaries and outlaws, so those on the run were viewed, from the earliest days of the republic, with something of a romantic flair.” Here’s what else these true crime writers had to say.

Why exactly did you decide to write a book about fugitives?

Ed Palattella: Jerry’s law enforcement experience gave us lots of material for the book, and we decided to write it about four years ago. But first we had to write A History of Heists, about bank robbery in America (2015) and Mania and Marjorie Diehl-Armstrong, about one of the main defendants in the notorious pizza bomber case. As an FBI special agent, Jerry helped run a joint violent crime and fugitive task force in Dayton, Ohio, and we often discussed his stories of tracking fugitives. We thought looking at fugitives on a national level would be fascinating. The fugitive is an iconic figure in the history of American crime.

What did your research for the book entail?

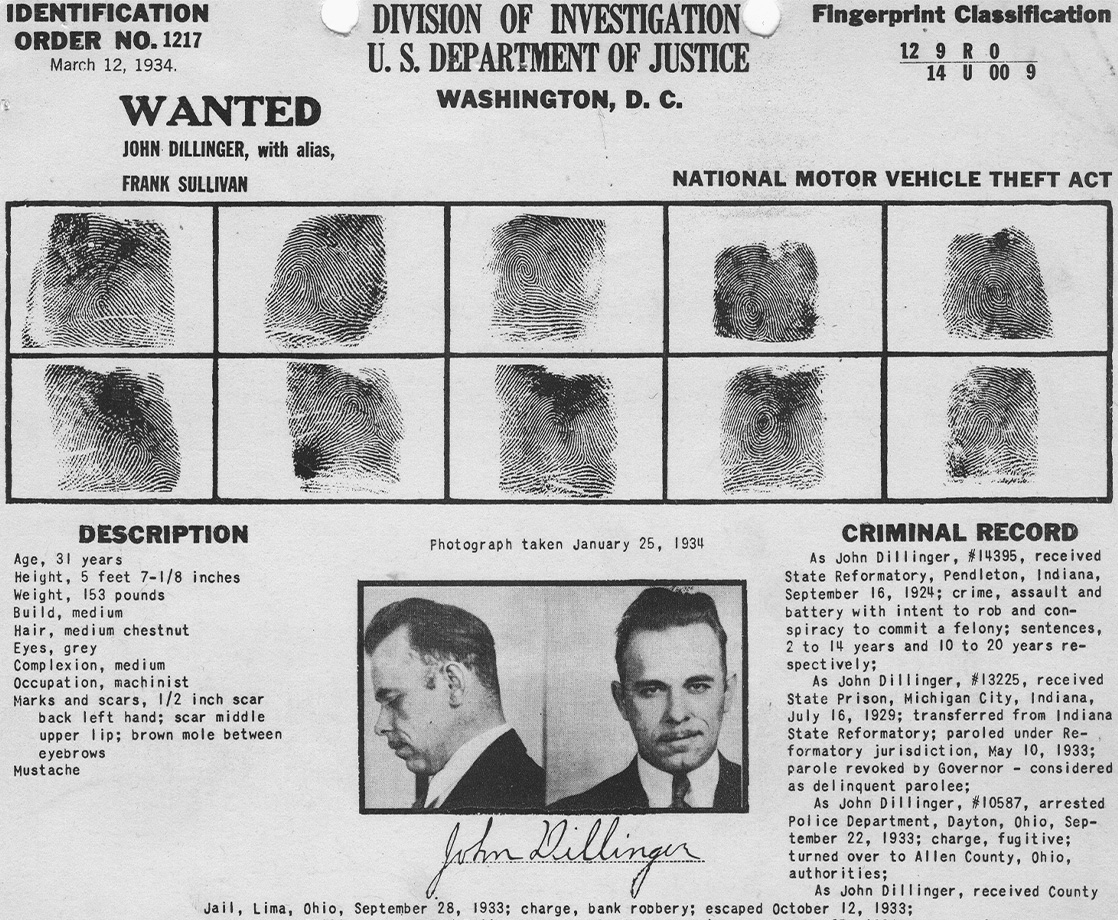

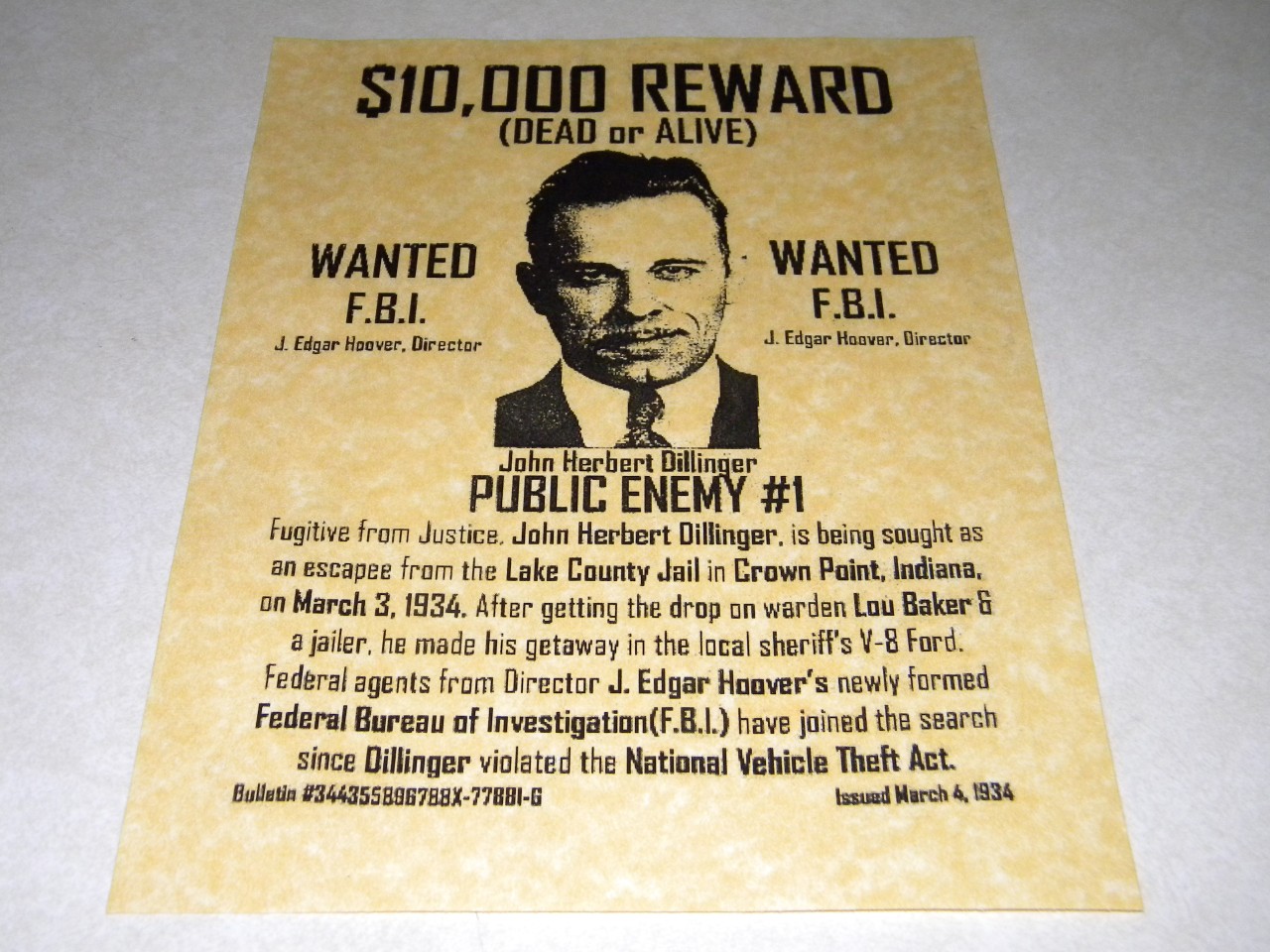

Jerry Clark: We read quite a few books about the history of bail and about fugitives, such as John Dillinger, Willie Sutton, and Whitey Bulger. We interviewed experts in law enforcement and researched newspaper archives to get an idea of how the public has viewed fugitives over time. The FBI archives, especially older documentaries, such as You Can’t Get Away With It! (1936) were also helpful.

What did you learn about the bail system while writing this book?

Palattella: We learned how old the system is. It dates to ancient times and was a key piece of early Anglo-Saxon law, which served as the foundation for the American criminal justice system. The bail system is critical to the proper functioning of the justice system because the courts must make sure defendants appear. But the criticisms of the bail system, including that it penalizes the poor, are often valid. Most defendants will show up at a hearing or trial. But Congress has changed the bail system to address popular concerns about crime.

Above, Jesse James after being captured

Your chapter “Long Arm of the Law” is about the US Marshals. What do you find unique about the Marshals’ role in criminal justice?

Clark: The FBI has a big hold on the popular imagination. But the US Marshals Service is the United States’ oldest federal law enforcement agency. Its marshals and deputies have been the foes of fugitives since Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1789, which also created the federal judiciary. At the same time, Congress has assigned the US Marshals Service a variety of duties over the years, including keeping federal courthouses secure. So their role was sometimes confused in the popular imagination.

After a series of reforms, the federal government clarified the fugitive-catching responsibilities of the US Marshals Service and the FBI in 1979. As set forth in the 1979 agreement, the marshals are responsible for finding escaped federal prisoners, federal bail jumpers, and federal offenders who violated probation and parole. The FBI still has jurisdiction over finding fugitives in certain high-profile cases, though. FBI special agents search for fugitives whom state and local authorities have accused of “crimes of violence, high property loss, and illicit narcotics traffic,” as well as escaped convicts accused of committing crimes. The two agencies frequently work together nonetheless.

What’s the craziest fugitive story in your book?

Palattella: Nearly every fugitive story is crazy in its own way, just as many crimes include a touch of the bizarre. But the story of Robert Elliott Burns might be the most unique, because, as a fugitive, he was largely on the run from an unfair and inhumane penal system in Georgia in the 1920s and 1930s. Burns escaped the chain-gang system twice, in 1922 and 1930, and his escapades while on the lam were immortalized in his best-selling memoir, I Am a Fugitive From a Georgia Chain Gang! and a hit movie, I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang. Burns’s tale has faded over the past century, but at the time he was the most famous fugitive in the United States. His experience spurred reforms in Georgia and caused many other states to also examine how they treated prisoners.

In Chapter 3, “The Search for Handsome Johnny,” you talked about the birth of the “Most Wanted” lists. What’s the significance of this development in the criminal justice system?

Clark: The origin of the most-wanted lists is linked closely to the creation of the category of “public enemy,” or a criminal so dangerous that the government considers him or her an outlaw of the highest — or lowest — order. “Most Wanted” posters from the Old West provided a means of publicizing fugitives, and those posters provided the framework for the posters that the FBI, US Marshals, and other law enforcement agencies created for fugitives. The public-enemy lists, in turn, provided the framework for the “Most Wanted” lists.

How does the “Most Wanted” list compared to the “Top Ten” list that you detail in the chapter “Infamous and Elusive”?

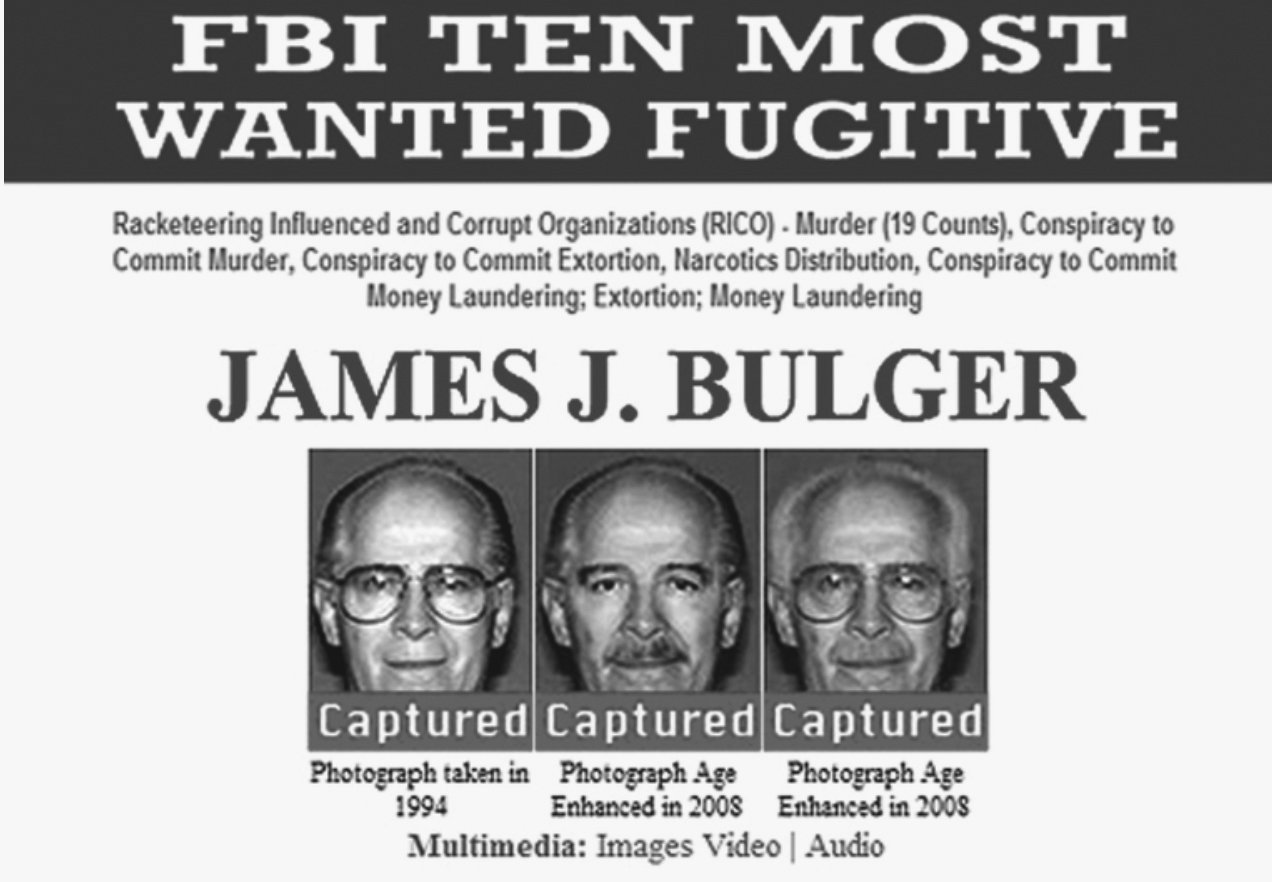

Palattella: According to the FBI, its top ten listed originated in 1949, when a wire service reporter, desperate for news, contacted the bureau headquarters in Washington, D.C. and asked an agent he knew for a list of the “toughest guys” that the FBI wanted to bring to justice. The reporter’s article proved so popular that the FBI introduced its Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list in 1950. The US Marshals Service followed much later, in 1982, with its Fifteen Most Wanted fugitive program. Both lists relied on the media to aid law enforcement. By publicizing the fugitives they could not catch, both the FBI and the US Marshals Service broadcasted their own shortcomings, though the public became fixated on the lists. Who doesn’t want to help catch a fugitive?

Why do you think fugitives are romanticized in pop culture, and do any particular fugitives epitomize their popularity?

Clark: Just as many people might fantasize about catching a fugitive, many others might wonder about what life would be like on the lam, particularly if they had been wrongly accused. The innocent fugitive has been a theme dating to ancient myth, though in reality, most fugitives are guilty and are fleeing from a just fate. In any case, the innocent fugitive is what is most appealing in American culture, which is why Richard Kimble is probably the best-known fugitive for most Americans.

As the fictional character in the TV and movie versions of The Fugitive, Kimble was a fugitive to root for because he was wrongly accused — and he was searching for the man who really did kill his wife. Kimble as a fugitive embodies, as the literary critic Stanley Fish has written, “a man who wants nothing but to be free — free not merely from the physical constraints of prison and the death penalty, but free from anything and everything.” And as Michael Zagor, one of the writers of the final episode for TV’s The Fugitive, once recalled:“Everybody’s fantasy as a little kid is, what would you do if you were falsely accused? Where would you go? Where would you run?”

Gallery — Photos of Cops Smoking Weed:

What was the most surprising thing you learned while writing the book?

Palattella: Fugitives are never free, no matter what they think and how long they are on the lam. Some fugitives believe they will never get caught and that they will escape justice, but they can never relax. All of the fugitives covered in the book lived with a sense of foreboding while they were trying to stay hidden. The lack of glamor for the fugitive came as something of a surprise.

What takeaways do you want readers to come away with after reading the book?

Clark: How much of law enforcement, especially federal law enforcement, was created to capture fugitives. Also, how deeply ingrained the fugitive is in American culture, which makes sense. The United States originated as a nation of rebels and revolutionaries and outlaws, so those on the run were viewed, from the earliest days of the republic, with something of a romantic flair. Even public enemies were considered fascinating because they were so bad. And yet America also has a deep affection for law enforcement. The tale of a fugitive gives Americans two characters to follow or even admire: The fugitive and the cop who is on the trail.

What did you learn about the mindset of living in the run as you discuss in Chapter 6, “A Mind at Unrest”?

Palattella: No fugitive can escape the dread of knowing that, eventually, the chase will end with a capture or death. Perhaps the most chilling words about the psychological suffering of the fugitive came from Willie Sutton, who was one of the best at staying on the lam. “I found it strange to change identity every time someone seemed to be catching up with me, and when a man changes his identity, he begins to think more deeply,” Sutton said. “It’s hard to be somebody different, over and over again. You’re never sure of who’s around you.”

What are the most common ways that fugitives get caught?

Clark: Most fugitives get caught because so many people are looking for them. Many times a fugitive will blow his or own cover by talking too much, or a friend or relative will turn them in. In Erie, Pennsylvania, the Erie Times-News, where Ed works, runs a most-wanted feature on local fugitives every Thursday morning. Those with information are asked to call the county sheriff. Many times, the sheriff said, the messages will come into his office’s phone at 5 AM or 6 AM on a Thursday — as soon as the paper hits the stands and the front porches. The reason: Fugitives can have lots of enemies, some of whom they are trying to escape.

You end the book with a chapter on fugitives in the digital age, including how much harder is it to go on the lam due to social media and the internet?

Palattella: Social media makes living on the lam more difficult for two main reasons: Facebook and other platforms allow law enforcement to reach more people, and some fugitives cannot resist staying off social media, either directly or through photographs their friends and relatives take and post.

After writing the book who were the most clever fugitives and why?

Clark: Those fugitives who have enough brains and enough self-confidence to keep their mouths shut and not boast about their exploits. Whitey Bulger, who knew how the mob kept secrets, was able to stay a fugitive for so long — 16 years — because he kept a low profile and did not feel the need to blather on about his past. Successful fugitives, if such criminals exist, are much like the most successful law-abiding citizens. Those who succeed have the most common sense.

“On the Lam” is out tomorrow, September 17th, through Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Order your copy here.

Follow Seth Ferranti on Twitter