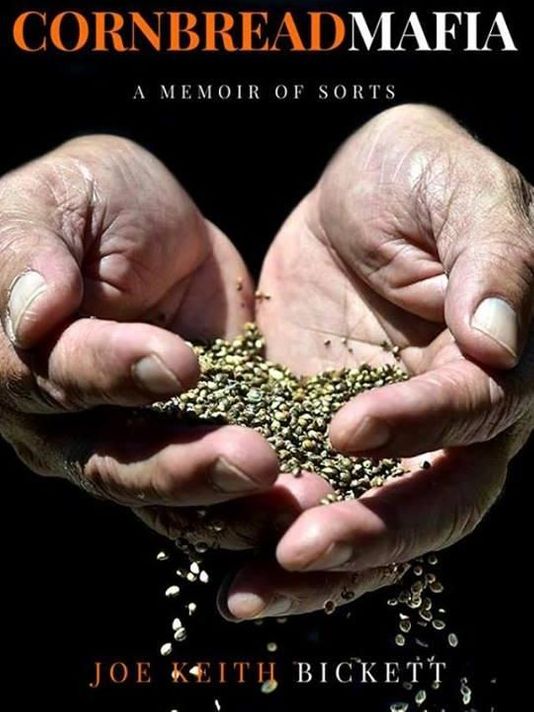

All photos courtesy of Joe Keith Bickett, book cover photo by Jim Higdon

When I got locked up in 1993 for a first-time, nonviolent LSD conspiracy, I was sent to Federal Correctional Institution Manchester in the foothills of Southeastern Kentucky to begin my bid. Upon arrival, I started hearing the stories of the infamous “Cornbread Mafia,” a group of outlaw cannabis growers who originated in the town of Raywick in Central Kentucky. Raised at the height of the moonshine era in absolute poverty, these ganja aficionados eventually created business interests centered on marijuana cultivation in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, just as the black market alcohol trade was diminishing.

These early homegrown pot farmers were a ragtag collection of hippies, Vietnam vets, criminals, stoners, and businessmen; they got the “mafia” moniker due to their outlaw spirit rather than Italian tradition. They were a rebel syndicate, of sorts, and referred to marijuana as “cornbread” to throw off authorities. Even though I was getting some killer Kentucky outdoor bud before I caught my federal case in Virginia, I’d never heard of the secretive Cornbread Mafia until after I was incarcerated. Chances are the top-shelf grass I was slanging was grown by them.

By the time I got to Manchester, a lot of the crew members had been locked up and fighting cases repeatedly since the early 1980s. Johnny Boone, known to some as “The Godfather of Grass,” was the most legendary member of the crew and its unofficial leader, but others members like Joe Keith Bickett and his brother Jimmy were equally vital to the organization. Together, these guys were anything but small-time pot farmers. In 1987, Boone and his crew were arrested for operating 29 marijuana farms in and around Kentucky, with a product stash rumored to be close to 200 tons. The feds claimed they were one of the largest domestic growing organization ever, and (amazingly) not one member cooperated with the government or snitched on the other members of the crew.

In a new book, Cornbread Mafia: The Outlaws of Central Kentucky, member Joe Keith Bickett continues the saga he started in his first book, The Origins of the Cornbread Mafia. Again, Bickett weaves a tale of outlaws, the feds, and marijuana in a style that’s part-memoir, part-history lesson, and an overall indictment of the federal government’s War on Drugs. MERRY JANE talked to him to find out how the Cornbread Mafia changed the weed game in Kentucky, who the big players were, and how the former outlaw feels about the hustle in retrospective. Here’s what the one-time cladestine cultivator had to say.

MERRY JANE: How long have people been growing weed in Kentucky, and why do you think the underground business exploded in the state in the ‘70s?

Joe Keith Bickett: We started growing marijuana in the early 1970s during the Vietnam War and the hippie movement. Kentucky is rural area were tobacco was the main cash crop for many years. Tobacco at that time only sold for $2.00 or so a pound. So many tobacco farmers saw marijuana as a much better cash crop than tobacco, as did a lot of the large grain farmers in the area. Kentucky has one of the best climates for growing marijuana. Various marijuana strains adopt well in the area.

In Eastern Kentucky the national forest provided the people of that region [the space] to grow excellent herb. Near the end of my Origins book, we grew a huge crop in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky. I'm sure lots of growers there are doing quite well [today]. Kentucky is such a great state to grow marijuana, from the mountain area in Eastern Kentucky to the flatlands in Western Kentucky. Our crew, however, lived in the Central part of the state around the edge of the Bluegrass portion — just an hour from Louisville and Lexington. The soil and climate is perfect for the production of cannabis.

Can you tell me about the moonshine culture that a lot of Kentucky outlaws grew up around?

When I was a kid [in the ‘60s], lots of people were into moonshine and bootlegging — including my dad and many others. They never spoke about it and kept it to themselves. As I recall, very seldom did anyone tell on anybody during those times. I remember one time I was out in the woods and ran upon this huge moonshine still. I never said a word about it; it was a given. Just keep your mouth shut that was how we were raised.

The reason I started to grow pot was because I had worked several factory jobs when I first got out of high school. I farmed some tobacco and never got ahead, but I loved the land. I could foresee that in the coming years the pot business was going to grow in leaps and bounds, and so did many others in our area. A lot of my friends were coming home from the Vietnam War and they brought with them a new culture of smoking and growing herb.

How did the Cornbread Mafia change the weed game in Kentucky?

We started off by just planting seeds and later on we used "plant beds,” similar to what Kentucky tobacco farmers used when growing tobacco. Hydroponics followed with the introduction of clones. Much of it was trial and error. But in our area, unlike in Eastern Kentucky, we had vast fields of corn and "soybeans" to interspace our marijuana in.

Who were some of the big players of the Cornbread Mafia and where are they now?

Bobby Joe Shewmaker, who’s featured in my book, served 26 calendar years in federal prison and was released from federal prison in 2016. He’s back home in Marion County and was a big player back in day. Johnny Boone, who some call the Godfather of Grass, was a big player who’s now serving a 57 month sentence after pleading guilty to one count of superseding information. He’s incarcerated at FCI Elkton, Ohio. The law office I currently work in represented him in that matter.

Tommy Lee, another big player, was released from federal prison around 2006 and works as a truck driver now. Jimmy Bickett, my younger brother, was another of the main players. He was released from prison in 2007 and farms now. I am a law clerk/paralegal for the law Office of Elmer George and was released from federal prison in 2011. There are several other large players who requested to remain anonymous. I’ve always respected their wishes.

Prison group photo from Manchester: Johnny Boone in red cap; Joe Keith Bickett on the right; Jimmy Bickett on the left; Tommy Lee standing top far right.

Your book mentions how when you were arrested in 1980, the police swapped 150 pounds of high-grade pot they confiscated from you and replaced it with schwag. Can you talk about that?

There were a lot of good cops back in the day, but there were also a lot of cops who wanted in on the action, as well. The switch-up of the sensimilla pot in my 1980 case was just another example of cops getting in on the action. It was just happenstance that me and my lawyer found out about their bullshit that they pulled off. I'm sure there were many more instances of cops, sheriffs, and other law enforcement on the take, just like it is today.

How did the federal government’s mandatory minimums and sentencing guidelines affect the pot growers of Kentucky?

The mandatory minimums was the result of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. Both Democrats and Republicans were on board with this law. The Dems didn't want to look soft on crime so they went along with the mandatory minimums. This law affected the pot growers in a big way. If you got caught with 100 marijuana plants, which amounted to about a teaspoon of seeds, you were looking at no less than a five-year minimum. The sentencing guidelines were even worse. The feds could apply so many different "enhancements" to a sentence, so instead of a five-year sentence you might be looking at 10 or 15 years — unless a defendant cooperated and received a downward departure for offering substantial assistance [to the authorities].

On that note, can you talk about the code of silence among the Kentucky growers, and what it means to the marijuana business there?

The Code of Silence is not necessarily an Italian/Sicilian thing like the "Omerta,” although ours was basically the same thing. It’s real simple: A snitch is a snitch and a rat is a rat, but sometimes some of the agents employed both. The federal systems have so much power and the ability to apply so much pressure to individuals, so many defendants feel they have no choice but to talk.

There is another old saying; “If you can't do the time, don't do the crime.” Our crew was as solid as they came for a long time, and that was the reason we lasted as long as we did. No one in our original group would even think about ratting on each other. I made the mistake of trusting some guys that I should have known better to trust. They had little character. They were as weak as puppy piss. That and cocaine led to my downfall. But I made it through prison, got out, and I’m back with my family and friends. Despite it all, I'm happy where I am now.

Can you tell me about when the feds started cracking down on your crew? What was that like and how do you feel about it in retrospect?

Back in the 1970s, cultivation of marijuana was just a misdemeanor in Kentucky. However both Kentucky and the federal government subsequently increased [the penalties]. As you read my book, you will understand that some of the feds involved [with persecuting us] would go to any limits, regardless of constitutional rights and ethics, to see to it that we were all sent to federal prison. Me, my brother, and two others were the only ones in our crew that went to a federal jury trial. Regardless of guilt or innocence, we paid dearly for practicing our so-called constitutional rights.

I don't think it was the drug that caused the feds to come down on us so hard, but it was the simple fact that we were making lots of money doing so. That's what pissed them off. As I mentioned in my Outlaws book, it’s bittersweet that we spent so much time in prison over something that is much less harmful than tobacco or alcohol.

Above, Joe Keith Bickett today

Why did you decide to write a second book about your time with the Cornbread Mafia? What did you want to expand on or explore that wasn't in Outlaws?

The first book Origins of the Cornbread Mafia covered the origins of the term "Cornbread Mafia" back in the 1970s how it was coined when most of the prosecutions were just state level and possession of marijuana, regardless of the amount was only a misdemeanor in the state of Kentucky. The second book Outlaws explores how the federal government gets involved in persecuting pot growers and other drug defendants during the Reagan years, and how the feds, from my perspective, were willing to go far beyond the bounds of law and ethics to send most of us to federal prison.

What is the most noticeable difference between the two books? Do you consider the new one a sequel, or can you read them as stand-alone texts?

The second book is definitely a sequel to the first, as many of the same characters in the first book are also in the second book. It also tells about how many of us during those years got caught up in cocaine addiction, which caused, in my opinion, the downfall of our tight-knit group.

Do you intend to write more about the Cornbread Mafia? What stories or history are missing that you didn't cover in the first two books?

Yes, I intend to write a third book about my years in federal prison, the discontent, the harsh sentences handed down not only to the pot people but also other drug defendants, and the Cornbread Mafia members’ subsequent releases and where we are today.

Coincidentally, I am happy to say that I personally knew three guys in federal prison that President Obama eventually pardoned. As a "jailhouse lawyer,” I worked on their cases at different times over the year. I like to think that maybe in some small way I may have contributed to their releases.

Do you think the Cornbread Mafia is a household name? If not, should it be?

The Cornbread Mafia name is well known here in the state of Kentucky, and [its legacy] has been expanding nationwide now for many years. There have been several production companies that have shown interest in producing a documentary, perhaps a series, and even a potential movie about us. Who knows what the future might hold for the Cornbread Mafia.

"Cornbread Mafia: The Outlaws of Central Kentucky" is out now. Order your copy here