All photos courtesy of Jack Riley

El Chapo first came up on DEA agent Jack Riley’s radar in the early 1990s, right before the cartel kingpin broke out of prison the first time. Back then, the DEA was primarily occupied with Colombia’s Medellin and Cali cartels, and El Chapo’s Mexican traffickers were viewed as a loosely-tied group of smugglers that were basically just muling for the Colombians.

But while the DEA focused on Colombia, El Chapo was beginning to make a name for himself, not only as a drug lord and mass murderer, but as a logistics genius, too. He was the first guy that really put together the theory of using tunnels to get narcotics out of Mexico and deliver it to certain cities in the United States. Eventually, El Chapo’s empire and the Sinaloa cartel became the DEA’s number-one target.

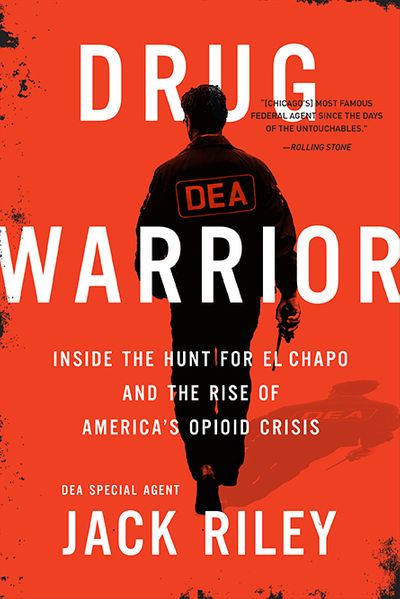

Riley offers readers an exclusive on the 30-year mission to bring El Chapo to justice in a new book, Drug Warrior: Inside the Hunt for El Chapo and the Rise of America's Opioid Crisis. With chapters like “Get Shorty,” “Border Town,” and “Public Enemy Number One,” the former DEA agent recounts his history as a narcotics officer and highlights the successes and (many) failures of the War on Drugs. MERRY JANE talked with Riley to find out why he decided to write a book about his career with the DEA, how he reacted when El Chapo put a price on his head, and why it felt like the “Super Bowl” when the drug lord was finally convicted.

MERRY JANE: What made you decide to write a book about your career with the DEA?

Jack Riley: I had no intention when I retired, but I had a lot of people push me and say we should tell this story. And also at that point, El Chapo was getting glorified. I wanted to set the record straight and make sure everyone knew just how heroic some DEA agents, policemen, and prosecutors were in their pursuit of him. If they had given up, he wouldn't be sitting in a cell in New York. I'm very proud of the agency and the job they’re doing today around the globe.

When did El Chapo first land on your radar?

When he earned the nickname El Rapido, which basically meant “the quick one.” He was guaranteeing customers that he could have product in the US within 24 to 48 hours. It was the first time we'd ever seen somebody that particularly organized and dedicated doing what he was doing. Once he broke out of jail in ‘92, he began to expand and take over much of Mexico. He did that through corruption, and, quite frankly, just killing people and violence. [The Sinaloa cartel] grew very quickly [as did] his influence, both among the traffickers in Mexico but also [with] the Colombians and the major cell heads that were working for him in the United States.

As he gained power, he was also smart enough early on to stay out of the limelight. He pretty much hid in the mountains of Sinaloa and ran his operations from up there with very little fanfare. Later on in his career, he came down off the mountain and went into a couple of highly populated areas, which probably hurt him — but helped us. Other than Osama Bin Laden, this guy's the number-one bad guy of our generation. He's responsible for tens of thousands of deaths. I don't think the American people really understood the extent of his organization. Sinaloa, at its height, was clearly the most well-financed and vicious criminal entity we'd ever seen.

Jack Riley pictured above

El Chapo put a price on your head during the investigation. Explain when you first found out about that, what you thought, and how you dealt with it?

I was promoted to the Special Agent-in-charge position in El Paso in 2007, and that's a pretty big job. It has about a third of the US-Mexican border as its territory. At that point, Juarez was aflame, and it was a battle zone. Chapo's Sinaloa cartel was fighting what was left of the Juarez and the Gulf cartels, and it was really a battlefield. I got down there and was interviewed by a newspaper, and I said, “I'm here to disrupt Chapo, get him in jail, and hurt his organization.” He evidently read that, and some Mexican officials let us know that they had picked up some information that he’d put a bounty on my head and wanted my head cut off.

In those days, you really had to kind of pay attention. In law enforcement, you get threats from bad guys, and you kind of blow if off as part of the job. But [the El Chapo threat] certainly got my attention, and we began to do things a little bit differently. I was concerned at the time for all of the employees, agents, and non-agent personnel down there, too. It kind of woke us up and showed that this is for real, but it also showed one of the things I was proud of — it showed that I was getting to him, that we had some operations that hurt him pretty good.

The biggest change in the last 15 years, and one of the things that Chapo and others really thought was happening, is the cops weren't talking to the [Mexican] cops. They [assumed] the good guys weren't talking to the good guys, and we weren't connecting the dots. That's what they were betting on. We've really come a long way now, not just with our Mexican counterparts, but sharing information with our state, local, and federal agencies, and making sure we are connecting the dots, because that's the real way to damage an organization, and I think we've done that.

What do you think are the elements that are fueling the current opioid epidemic in the United States? And what role do the cartels play in that?

We know from some of the intelligence information we've developed — and it came out in the [El Chapo] trial, too — that those guys foresaw the dependence on prescription drugs and the connection to opioids. If you are prescribed drugs and abuse those drugs, at some point, the doctor won't write the prescription [anymore], and you can't get the pharmacy to fill it. You can't go to your grandmother's house and steal it out of her medicine cabinet 'cause that's all gone, but you're still addicted. That leads to the long, dark road of using heroin. And in Chicago, [a major distribution hub for heroin], we saw Sinaloa hook up with nearly 100,000 street gang members who did nothing but put the dope on the street. So you’ve got people addicted to prescription drugs moving to heroin and fentanyl.

I think there are a couple of things that caused the opioid epidemic: number one, the medical community really wasn't up-to-date in terms of how they should prescribe painkillers. A doctor told me a number of years ago that, at one point, students going through med school would receive about eight hours of pain management instruction. I also think Congress's cozy relationship with the major pharmaceutical companies has really put a dent in the DEA and other law enforcement agencies going after these companies. You can fine Cardinal Health $150 million, and they write a check. It's like taking a truckload of narco dollars from Chapo — it's the price of doing business.

What we really need to do in this country is to go after the CEOs of those companies who knowingly, and continually, break the regulations and laws, and put 'em in jail. If we put those guys in jail, a millionaire CEO in a Brooks Brothers suit is not going to do well in the prison yard playing kickball with some felons. It's gonna send a message that they've gotta be held accountable. Congress has got to reevaluate their relationships with the pharmaceutical companies and the lobbyists. That's the root of a lot of the problems. Also, people didn't wanna believe that there was an addiction problem in their high school or their neighborhood. And we've come a long way on that, obviously, but what we've gotta do now is we've gotta concentrate on education.

I'm not talking about sending a uniformed officer into an elementary school and saying "drugs are bad" to third graders. No, I'm talking about reaching out to the people who are the most at-risk — our young adults, our young professionals, people that find themselves in the grips of addiction, and wanna do something about it. We've gotta get people into treatment who want it. The federal government needs to put some money behind that if we're ever gonna get ahead of this.

You spent over a decade hunting El Chapo. How did his capture, extradition to the US, and ultimate conviction make you feel?

For me, it was the Super Bowl. So many years chasing a guy, seeing what he did to our cities across the country, seeing what he did to heroic DEA agents and police officers all over the world. He's where he belongs. I know the case, I know the evidence, I know the prosecutors, and I know the agents. He's not getting out of jail. I was prepared to retire the last time he got caught, but I knew if we didn't get him extradited, something was gonna happen, and indeed that's what happened. We had already been pressuring the Mexicans for a quick extradition. I think his last escape was kind of a national embarrassment to Mexico. And I think that everything was moving in the right direction. So the day that we put him on a plane to bring him up here was my last day. I retired right after that.

"Drug Warriors" is out now via Hachette Books. Order your copy here

Follow Seth Ferranti on Twitter