All photos courtesy of Richard Stratton

In the 1970s and 80s marijuana culture in the United States was basically illegal, illicit, and underground. With the passage of the Controlled Substances Act in 1970 marijuana was classified as a Schedule I drug. In 1971, President Nixon started the War on Drugs. And in 1973, the DEA was born — every stoner’s worst nightmare. As the government vilified marijuana, drug smugglers like Richard Stratton went on the offensive.

At his peak, Stratton was bringing in 30 to 40 thousand pound loads of marijuana by boat from Colombia several times per year — orchestrating deals that kept swaths of America high as fuck. Stratton is a tried and true OG of the weed game: On top of his smuggling, he was also leader of the so-called Hippie Mafia, co-founded High Times with publisher Tom Forcade in 1974, wrote for Rolling Stone, and hobnobbed with Norman Mailer and Hunter S. Thompson. And despite the fact that he never shot or killed anyone, or even carried a weapon, he was arrested, convicted as a drug “Kingpin,” and sentenced to 25 years in federal prison on marijuana trafficking charges. In other words, he was an early trailblazer and advocate of the legalization movement the nation is collectively embracing today.

Stratton won his appeal, but still served almost 10 years in federal prison where his reputation as a jailhouse lawyer was legendary. He founded Prison Life magazine when he was released, and also became a filmmaker, producing Fallen Champ: The Untold Story of Mike Tyson, Street Time, and I Married a Mobster. Smugglers Blues — published last year and focused on his time in the Hippie Mafia — was the first in a trilogy of books documenting his life.

In the second installment, Kingpin: Prisoner of the War on Drugs, released May 2 by Arcade Publishing, Stratton looks back on his journey into the criminal justice system and netherworld of corruption and violence that defines it. The memoir-style book “picks up where Smugglers Blues left off,” says Stratton. “With me in custody in the Los Angeles County Jail, also known as the Glass House, possibly the worst jail in America.”

The book documents the sacrifices he made so that we could smoke pot, and analyzes the War on Drugs and criminal justice system from the inside out. MERRY JANE talked to Stratton by phone about the rise of the prison industrial complex and mass incarceration, how the Trump administration is trying to turn back the clock, and how it feels to be recognized as an original leader of the marijuana movement, fighting a battle that is still raging today.

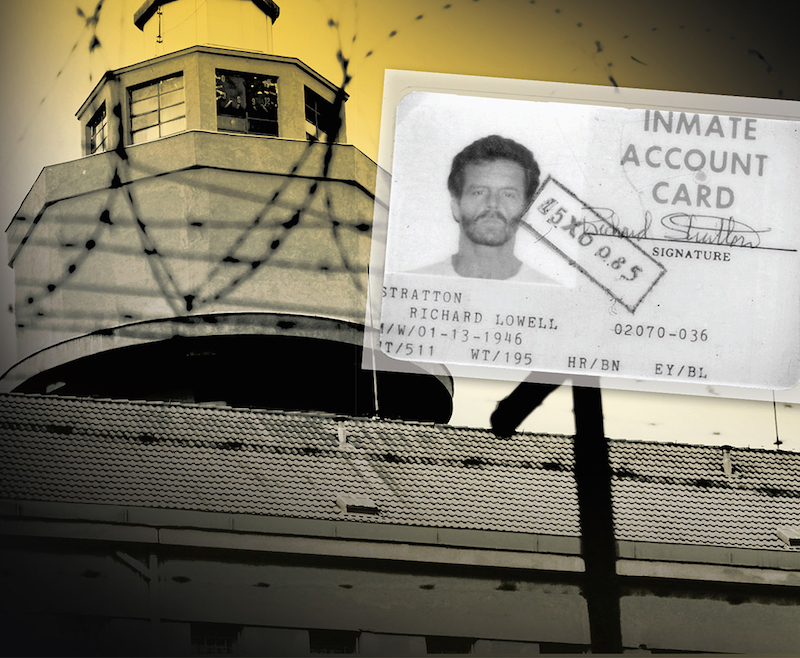

A photo of Stratton back in the '80s when he was in the feds.

MERRY JANE: How did you feel when you first got sentenced with 25 years in the feds for smuggling weed? At that time wasn’t that an extreme sentence?

Richard Stratton: That was the beginning of the sentence enhancements for smuggling pot in the 80s. I think before 1982, the most time you could get was five years, no matter how much pot it was. When I went to trial, I was facing a minimum of ten years up to life, with no possibility of parole because of the Kingpin Statute. The judge sentenced me to 10 years, but ran it consecutive to the 15 years I already had in Maine for a total of 25 years. [Stratton had two separate charges — a 15 thousand pound bust in Maine, and a subsequent federal conspiracy charge which alleged he smuggled in seven metric tons of hash.]

I was fortunate that the judge stipulated on the record that the reason she was running it consecutive was because of my refusal to cooperate. I was also fortunate because if I’d been sentenced two years later in 1986 I’d probably have a mandatory life sentence with no possibility of parole. It seemed like a lot of time, 25 years, but then when you compare it to life with no possibility of parole, I was very fortunate that the judge made the distinction on the record why she was giving me that much time. It was a mixed blessing.

Once you were convicted what motivated you to continue to fight your case? How did you get back in court and get your sentence reduced?

I was never one to lay down and take defeat. I remember thinking there’s no way I’m going to do 25 years. I’m going to fight this thing and if I can’t beat them in the courtroom I’ll escape. It seemed like a ridiculous amount of time to do for a plant. I knew that the government was completely out of their mind to try to criminalize this plant and lock people up. I went back on a Motion for Sentence Reduction. I said, “Judge, your sentence is illegal, it’s coercive rather than punitive.” She denied it. I appealed to the Court of Appeals. It took six weeks for them to rule, but ultimately they ruled in my favor and I was re-sentenced and the new judge ran my two sentences concurrent instead of consecutive. I ended up doing eight and getting out in 1990.

What are the major takeaways that you want readers to get from the new book?

The book takes you into the federal Bureau of Prisons and whole system in a way that is unique. Going through Diesel Therapy, being moved by the feds from one joint to another as a way to marinate you to the point where you just want to plead guilty. It’s kind of an in-depth experience of going through the whole criminal justice system from arrest, to trial, to the efforts the government made to turn me into a cooperator. The kind of agonizing decision you have to go through, even though it was something I was never inclined to do, but you think about it. They are offering you these great deals and you can walk out of these places or you can face life without parole. You have to think about [cooperation deals].

What surprised you the most when you were fighting your case in regards to the laws, how they were convicting people, and the War on Weed?

There was a huge amount of pressure they put on me to implicate Norman Mailer, Hunter S. Thompson, and some of the other people I knew from my other career as a writer working for Rolling Stone — people who were not really involved in drugs besides smoking weed occasionally. The thing that surprised me the most about the government was the length they’re willing to go to try and make these marquee-named cases. They wanted to lock up Norman Mailer. They wanted to lock up Hunter S. Thompson. It was the era where they were making drug cases against people like John DeLorean, big names. It was all about making drug cases to discredit, to make [revolutionary, progressive people] look bad in the eyes of the American public.

A recent photo of Richard Stratton

Smugglers Blues was the first in the book trilogy about your days in the Hippie Mafia, and Kingpin is the second that details your journey through the criminal justice. What is the third and final book of the trilogy going to be about?

The third book is called In the World: Life After Prison. That book is coming out a year for now. That book is broken down into three parts — Parole, Hollywood, and Fatherhood. I tell the story of being on special parole and how they fucked with me. I deal with my entry into the world of documentary filmmaking with the Mike Tyson film and all the stuff I did for HBO like Gladiator Days and the feature film, Slam. Getting married, having kids, and reconciling being a family man as an ex-convict and outlaw for so many years. A difficult transition.

What do you think of the new administration and all the noise they are making about possibly going after recreational weed and cracking down on marijuana?

My advice would be that Sessions and Donald Trump and all the rest of those nuts should sit down with a bong. They should all get high and then they should ask each other, what do we think we’re doing? Maybe they’d come up with some really good ideas. Now that this new lunatic is in charge and Sessions is talking about rolling back all these laws, I don’t think the American people will stand for it. I think they would throw all these bums out of office.

I think that’s a hard way to go about it, but still the point is it’s a plant. It was created by God. It was given to mankind as a kind of way of opening up our minds and giving us a deeper insight into things, and there’s no way it should be illegal. It’s ridiculous. It goes back to the whole Reefer Madness insanity of the Harry Anslinger and the Federal Bureau of Narcotics era, way back in the day. They had nothing to do, because booze had been legalized so they needed something. They needed an enemy and they made marijuana the enemy.

Given how marijuana is becoming entrenched as a legitimate industry how does that make you feel looking back concerning your ideals and how you took it upon yourself to make sure people had pot to smoke as a smuggler?

We changed the culture of America. The magazine High Times, the people I was involved with, we changed the culture of America. Before the so-called Hippy Mafia came along, America believed that if you smoked too much pot you would grow huge fists or you’d start shooting heroin. There were all kinds of insane things that they were saying. We knew that was bullshit and we fought it and we ultimately brought it around to the point where it was one of the most massive demonstrations of criminal, civil disobedience in the history of this country — where people just said the laws are crazy, the laws are wrong, and we’re not going to abide by them. We’re going to use this plant. We’re going to smoke this plant.

I hate to see where it’s going now. I’m a little concerned, because it seems to be turning back, but having gone through it, having lived through it, it’s very gratifying. I remember when we began High Times back in 1974, we knew that this day was going to come. We knew that ultimately someday it was going to be legal. We knew that Americans were going to wake up and say this is ridiculous, we’re locking people up for a plant? It’s a little concerning to me to see these huge corporations come in and try to take it over. I miss the outlaw days to some degree, but then again I also believe that pot is so easy to grow that people can grow their own. I don’t want to see people locked up for it. I think it’s a crime to see people locked up for pot.

'Kingpin: Prisoner of the War on Drugs' is out now — order it here.

Follow Seth Ferranti on Twitter