All images courtesy of FUEL

Here at MERRY JANE, the subject of prohibition comes up on a daily basis. We live in a country where our biggest entertainment events are sponsored by alcohol companies, but access to a plant with countless proven benefits is still restricted by the federal government. And even in states with recreational marijuana laws, those old enough to legally purchase cannabis grew up in an era where D.A.R.E. and other government-sponsored programs ingrained in our heads that weed is bad and the War on Drugs is for the greater good of our nation (despite evidence suggesting anything but).

That said, America’s War on Drugs and cannabis prohibition in the 21st century looks mellow as hell compared to what people living in the USSR experienced at the height of the Soviet’s power during the 1980s. In a new book simply titled ALCOHOL, Russian writer Alexei Plutser-Sarno and designers Damon Murray and Stephen Sorrell (the latter two released the book through their publishing house FUEL Press, and all three were behind the enormously popular Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopedia series) explore the draconian anti-alcohol campaign initiated by the Gorbachev administration by resurfacing the propaganda posters and ephemera that were disseminated to the public en masse.

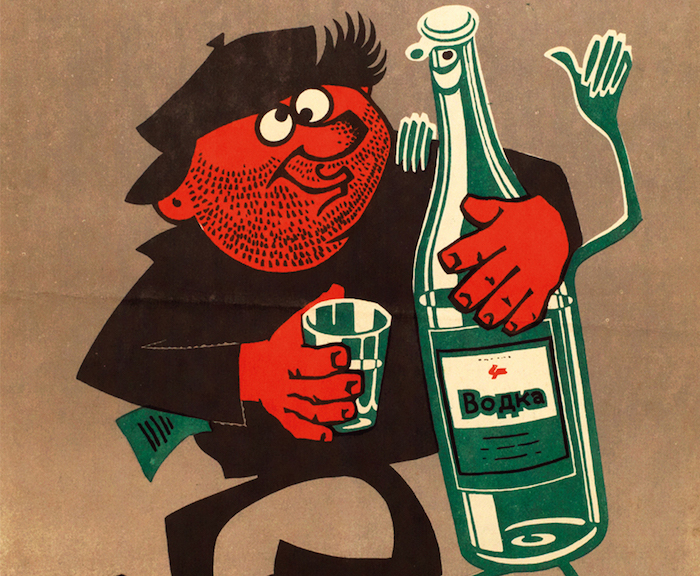

Caption reads: "Either, or." Text on the bottle reads: "Vodka." (1983)

In 1985, the government launched a campaign called “On Measures to Overcome Drinking, Alcoholism, and to Eradicate Bootlegged Alcohol.” As the authors explain in the text’s intro, “Hastily, conceived and lacking sufficient planning or preparation, it was an attempt by the government to cut through a historic Gordian knot of social issues with little consideration for the consequences.” And those consequences were major, to say the least. After shutting down 80% of alcohol outlets across the Soviet Union and enforcing limits to how much alcohol citizens could purchase at a given time, the economy was sent into a tailspin. By 1987, the government’s income had shrunk by 37 billion rubles, the national debt grew by 500%, and a black market economy began surging.

Bootlegged alcohol became the norm, though it was worse in quality and, in countless cases, lethal to consume. “Distilled form various kinds of organic waste or cheap, sub-standard ingredients (starch, sugar, low-grade grains, rotten potatoes or beets), it was also often contaminated with large amounts of toxic fusel oils,” write the authors. The public began consuming literally anything containing alcohol, from colognes, perfumes, and air fresheners, to brake fluid (a.k.a. “undercarriage liqueur”), insecticides, glue, and even de-icing fluid from aircrafts. Though these products were consumed by some before the propaganda order began, “now hundred of thousands — perhaps even millions — of people were drinking substitute spirits.” In 1987 alone, the death toll was expected to be around 11,000 from consuming poisonous alcohol replacements. Now imagine an America where all marijuana users were left with no choice but to smoke exclusively synthetic cannabis. Things wouldn’t turn out so good for us, either.

In response, Gorbachev launched an anti-bootlegging campaign that led to hundreds of thousands of people charged or fined well beyond their means. The regime even initiated a “detoxification system,” which was presented as a rehabilitation program including alcohol recovery centers, but in reality was a thinly-veiled excuse to lock up thousands of citizens for “crimes” like the appearance of drunkenness. In the early ‘80s, around 150,000 drinkers were held in the “therapeutic-labour institutions,” which were actually more like “horrific prisons,” where “these ‘patients,’ who received little treatment or therapy, were essentially slaves.”

The USSR’s anti-alcohol era lasted all the way through 1988, but the propaganda survived and the practice of drinking “surrogate alcohol” has continued into the present, though it's less rampant today than it was during prohibition. Below, MERRY JANE spoke with co-publisher Damon Murray over email to get some more insight about the incredible and sobering book, as well as spotlight a few of the surreal (and sometimes genius) propaganda posters that appear in it.

MERRY JANE: You and Stephen Sorrell curated, edited, and designed ALCOHOL, but you collaborated with Russian writer Alexei Plutser-Sarno, too. What was the collaboration process like?

Damon Murray: After starting to collect these posters, we wanted to collate them into a book. The images were so different from those we are used to seeing today on this subject, that we felt they needed a context to help the reader understand the circumstances in which they were created. It was important for us that the text had an authentic voice, reflecting events and attitudes of the time. We approached Alexei Plutser-Sarno (who had previously written for our Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopedia series), as he had first-hand experience of the period. Оur brief to him was straightforward: We wanted a non-judgemental introduction that would give our readers a real insight into drinking at a grassroots level. The final essay was edited into two sections ‘Surviving Gorbachev’s Prohibition’ — dealing with how the law was circumnavigated, and ‘Drinking Determines Consciousness’ — explaining the physiology behind Russia’s thirst for alcohol.

Can you tell me about how the book came to fruition? What was the research process like? Do you have any memorable stories about how and where you found the images featured in the book?

We came across anti-alcohol posters online and were staggered by how immediate they were. We discovered a large number of Gorbachev-era posters that had never been reproduced previously. They were collected from various sources: through contacts we’ve made in Russia, collectors, and online auctions. Everybody is familiar with the classic type of Soviet propaganda poster – usually featuring heroic workers building a utopian communist future. By contrast, these images described another more sinister and dystopian reality, where the promised future was being constantly undermined by the relentless consumption of alcohol. We thought these images would fit perfectly into a book as part of our Russian series, examining lesser-known areas of Russian culture.

Caption reads: "On the snake are various labels from alcoholic drinks. Not among trees or grasses/The serpent has warmed up among us/Don’t suck on him, mammals/Or you’ll turn into a reptile yourself." Ukrainian SSR (1972)

Besides focusing on Russia and taboo subject matter, does the alcohol book overlap or share any characteristics with the criminal tattoo series?

Obviously, Alexei Plutser-Sarno was involved in Volume I of the tattoo series and this project. But in terms of the subject itself, Gorbachev’s ‘dry law’ was a massive boost to the black market in bootlegged alcohol, and inadvertently a boost to Russian organized crime. In effect, alcohol production switched from being manufactured by the state to being manufactured by criminals (both in an organized way and a more personal, localized fashion). The laws effectively turned ordinary citizens into criminals – they had no other option. The book includes this ‘joke’ from the time:

A young boy and his father walk past an alcohol outlet with a very long queue. The boy looks at the people in the line, dumbfounded, and asks: ‘Dad, who are these people?’ He replies, ‘Those are loafers, son. They’re too lazy to build a still for themselves.'

What were the artists like who made these propaganda images? Some of the graphic design is truly remarkable. Outside this government-commissioned work, were you able to find other art by these designers?

The Soviet Union attempted to control the output of all artists. From fine art to graphic design, artists were expected to conform to the prevailing communist ideology. We found that a large number of the designers included in the book had also produced work for the government on a range of subjects, from space exploration to anti-American propaganda.

"His inner world" by P. D. Yegorov, Ukrainian SSR (1987)

What images from the book do you find the most interesting — any favorites or stand-outs?

It’s very hard to pick a single favorite – there are so many that I change my mind regularly. At the moment, I really like ‘UNDERPASS – to the next world’ (1988) by S. Smirnov [pages 74-75]. It is a simple but effective design that is practically malevolent towards drinkers — almost seems to wishing them to the 'next world.’ It also has a particularly Soviet feel — underpasses are common features in many Russian cities, used to reach the other side of prospekts, which are usually broad enough to host military parades.

Do you plan on doing multiple volumes of the book, similar to the tattoo anthology?

At this point, it’s difficult to say. Unlike the material we discovered for the Russian Criminal Tattoo series, we’re not certain that many more unseen posters actually exist. The current collection took over two years to amass, so even if it were possible, it would be a long process. We’d also have to see what audience such material will appeal to. We are a very small publishing house (just myself and Stephen Sorrell). We have no predetermined publishing strategy, and we don’t research how any particular subject will be relied by our readership. Our output is based on our interests and instinct as to what will make an interesting book for our list.

"Fight drunkenness!" Text on the bottle reads: "Vodka." (1977)

One last question — tell me about the book’s wild cover. How did you conceive the design?

We aim to make the design element integral to all our books. Coming from a graphic design background (we both studied at St. Martins and the Royal College of Art), we understand that this is a vital component of any book. The important factor for us is that the design fits the subject. We realized that with the anti-alcohol theme, we had the perfect opportunity to make a lenticular that would describe the issue visually. Lenticulars are normally associated with children (cartoons, images of animals, etc.), but we want to produce a grown-up, intoxicated version. Taking the basic elements of an original Soviet drawing from the 1980s, we animated it so that the ‘hero’ ceaselessly poured a bottle of spirit into his shot-glass head in an eternal binge.

Caption: "Don’t drink your life away." By I. M. Maistrovsky (1977)

Caption: "Rowdy partying ends with a bitter hangover." The text on the tattoo reads "I love order." By P. Sabinin (1988)

Caption: "Little by little, and you end up with a hooligan. Tolerance of drinking is dangerous. There is but a step from drinking to crime." Artist unknown (1986)

Caption: "This is a shameful union – a slacker + vodka!" By V. O. Pushenko, Ukrainian SSR (1980)

‘ALCOHOL’ is out now through FUEL Press. For more information, visit the publisher’s website here.

Follow Zach Sokol on Twitter.