All images courtesy of Feral House

If you’re not from Portland, Oregon, and someone mentions the city, what’s the first thought that pops into your head? Maybe it’s Fred Armisen and Carrie Brownstein’s sometimes-accurate, mostly-obnoxious sendup, Portlandia. Maybe it’s the city’s biggest exports: coffee, indie rock, and craft beer. Maybe, if you’re hip but lack a sense of history, you think of Drake and Travis Scott’s new favorite city.

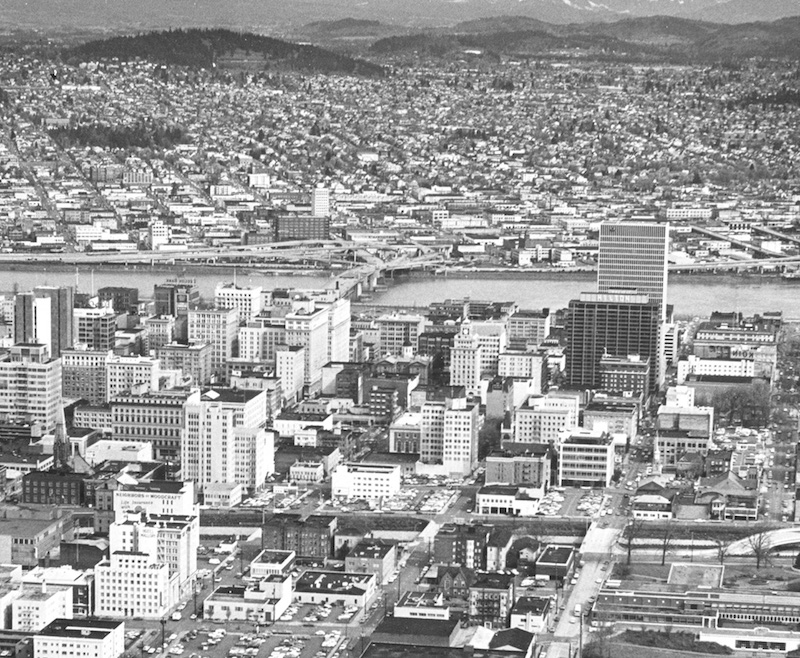

Whatever piece you personally latch onto, Portland’s current reputation is green and temporal. The Rose City, as it’s nicknamed, has only recently become a recognizable and (possibly, depending on your tolerance of rain) desirable locale in the general American consciousness. But before it was Portlandia, or Nike HQ, or Travis Scott’s “fav place in America,” or one of the most progressive states in the push for nationwide marijuana legalization, it had a much seedier reputation.

Starting with a shanghaiing epidemic in the early 1900s, the Rose City of the 20th Century was a far cry from the rapidly-gentrifying hotspot it is today. A 1911 city commission noted that 431 of its 547 operating hotels were “wholly given up to immorality” (i.e. prostitution); prohibition didn’t stop over 100 speakeasies from operating in the city; a 1969 article in the New York Times beamingly described the city as a “bomb site of parking lots.” In many ways, the idea of the Wild West lingered in Portland until pretty recently.

Along with the urban decay, prostitution, gambling, and drugs came, inevitably, corruption. This is the story of many American cities in the early-to-mid 20th Century — Chicago, Baltimore, New York, etc. — but few have a history of payoffs and cover-ups as rich and untapped as Portland.

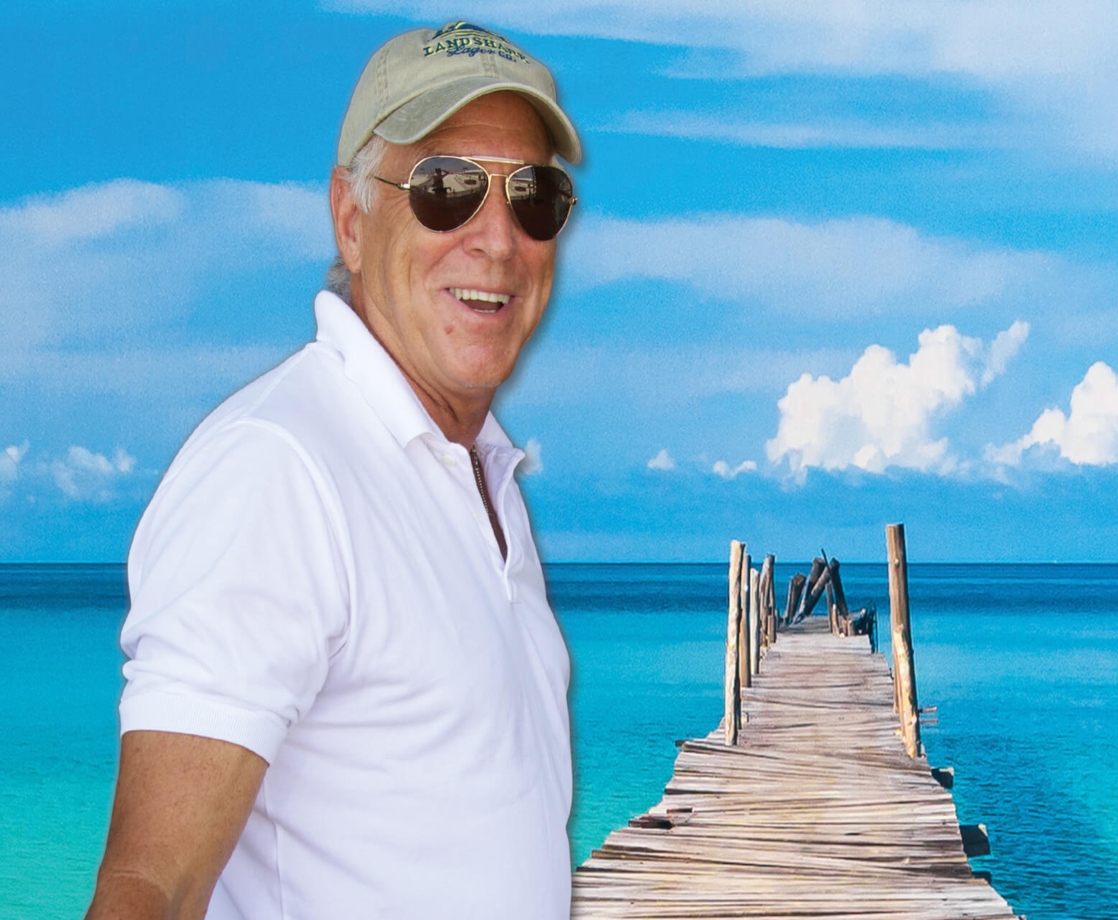

Phil Stanford arrived in town in 1988, fresh out of Miami where he worked as a private investigator. Starting off as a columnist for local paper The Oregonian, he quickly became devoted to uncovering the wrongdoings of police and elected officials in the area, his first big break coming when his investigation of a serial killer freed two innocent suspects from jail. He’s written several true crime books about various moments in the city’s history; Portland Confidential tackled a vice scandal of the late 50s, The Peyton-Allan Files uncovered the mystery of a 1960 double-murder. But his latest is the most involved, and the most damning.

Rose City Vice (out May 16th via Feral House) covers roughly a decade of corruption in ‘70s and '80s Portland, stretching from low-level vice cops all the way up to the governor’s office. Nearly every imaginable civic scandal, from police stealing drugs and selling them to biker gangs, to former governor Neil Goldschmidt carrying on a sexual relationship with a 13-year-old, makes an appearance. Some have been whispered about for years, but most are mysteries even to Portland’s longest-tenured residents.

Galloping along at a brisk, engaging 95 pages, Rose City Vice belies the fact that it was thirteen years in the making. Stanford ran into obstacles at every turn, largely unable to get anyone in law enforcement or government to talk to him. The type of corruption the book describes isn’t exclusive to Portland, but the city’s seemed to maintain a cover-up much more effectively than most others. As a Portlander myself, I was curious to hear Stanford’s personal tale, as well as the painstaking process by which he acquired all the book’s information, so I met with him at his home in Southeast Portland for a chat about his latest deep dive into the city's netherworld.

The following has been edited for clarity and length.

MERRY JANE: When did you first become interested in the untold history of Portland’s corruption?

Phil Stanford: I came to the city in 1988 to work for The Oregonian. While I was here, it became evident that there was a lot that had gone on in Portland’s history that people just didn't want to talk about. The first book I did [Portland Confidential] was to find out what really happened with a vice scandal back in 1957. I finished that 13 years ago and then started on Rose City Vice, but I ran into obstacles right away because everything was covered up. Back in one 1950’s scandal, there'd been a senate investigation and a state police investigation, so I thought this would be easy, but it took me all this time to put it together.

Of course cops have never wanted to talk to me, so what I did in the first book, Portland Confidential, is get a lot of basic information from people who'd been in the underworld. Especially after the statute of limitations was run on everything but murder, most of them were pretty willing to talk because they understood the game, which is that narcotics cops choose up sides with one half of the dealers against the other half. The guys on the cops’ side turn in their competition. That leads to corruption very quickly because police see all this money that they think might as well belong to them. Here, as elsewhere, [cops] were putting the drugs back on the street. They'd bust someone, but instead of arresting them they'd say, “You're working for us,” and they would end up taking most of the money.

That's one of the many things I had to string together for this book. There were people in very prominent positions in this town who were financing the deals, and they were completely protected too — they were friends of the D.A.'s office. And so what you had during the ‘70s and ‘80s, even more than in the ‘50s, was a very successful cover-up [of widespread corruption]. It took a long time to penetrate that.

What eventually got you the information you needed to write the book?

It was very hard to pin it all down, because none of the dirty cops want to talk about it, and their colleagues who are more or less on the straight-and-narrow don't want to talk about it either because those are their friends. I did get some help from some high-ranking police officials before I was through. One in particular was Norm Reiter, who was a captain and a head of the vice squad at one time, and was a very honest man. If Rose City Vice has a hero, it's Reiter. But most of my information came from talking to people who'd been in the drug business. A lot of my best friends are retired dealers.

Why do you think it’s so difficult to investigate the history of corruption in Portland, compared to other cities?

The ‘70s in Portland was [defined by] a decade of cover-ups, and no one had an interest in [investigating them]. Part of that comes from it just being a one-party state. Say, in New Jersey, another party comes in after ten years and they prosecute the previous office-holders, then ten years later, the same thing happens. This has been a one-party state since 1957!

Another part of it was that the D.A., Michael Schrunk, was the son of Terry Schrunk, who was the last of the big Portland payoff mayors. Payoffs were still running full steam while he was in office. Mike’s primary goal as D.A. was to keep the lid on, because once you've lifted it up, it went back to his sainted father, and he could never allow his father to be embarrassed, even though his father was part of a long tradition of corrupt mayors. He recently retired after 30 years in office. It's safe to say that Portland's cover-ups were a good deal more effective than in most other cities where, of course, the same thing goes on.

The book highlights that the city was still pretty conservative in the ‘70s. What allowed it to be simultaneously awash with prostitution and drugs?

Portland's always been a strange mixture of that rough, dark side and a quirky, intellectual side. It used to be a lot more of a working class town. It was a port city, there were a lot of steelworkers, and that much has changed.

Back in the ‘50s, they had to raid the gambling places every once in awhile because everyone could see them operating, but they would call ahead and warn them, tell them to move their roulette tables into the back room. With drugs, it became even more outrageous, because many of these officials were doing coke, especially in the ‘70s. It was pervasive! I've talked to D.A.s who've smoked dope inside of the D.A.'s office. As far as coke goes, that was the professional drug of choice, and when it started out, no one thought you could get addicted. Everyone was doing it even though it was against the law. So that even intensified the hypocrisy — they're talking about saying “no” to drugs, but they're doing them themselves, and they're buying them from the very people who they're supposed to be arresting. So of course, they let [some dealers] slide, and they arrested their competition — same old game.

You mention that some sources weren’t that forthcoming about cases that haven’t been solved. I know you’ve had success with freeing innocent parties by revisiting cases in the past — any chance of those being reopened?

The book, for all its disclosures, ends as sort of a mystery. The biggest example is a lawyer who defended a member of a biker gang who shot a cop during a raid on the gang’s headquarters. He had a private investigator who ended up dead about a week after he told the bikers that he was onto some information that was going to spring the client, because he had the cops who did the raid on two murders. A week later, the P.I. was found in his home shot to death by his own service revolver, and they called it a suicide. I don't think that'll ever be solved. It wasn't investigated, even though the defense lawyer thought the P.I. had been murdered. They made a deal and they covered it all up. No one was ever prosecuted on that, so there's no one to free, like some of the other cases I've worked on. Especially looking at murders that might have been committed by cops, it's just not going to happen [laughs]. So no, the book doesn't really offer any encouragement that justice is going to be served.

I recently saw a story in The Oregonian that reminded me of something in the book. Police found that an owner of eight Portland strip clubs and two adult video stores was using them fronts as fronts for prostitution. Do you think this was a remnant from the ‘80s, when he started some of those clubs, or merely an outlier in this current era?

It's not surprising. Strip clubs are always straddling the legal and the illegal. Some of the girls do not prostitute themselves and some do. I think that's always the way it's been. It's always going to happen. The police, if they are inclined to enforce the law, can't arrest everyone, so it's always very selective. Back in the payoff days, there was a formal arrangement. They paid the cops a certain amount of money every month and they were allowed to operate, as long as they didn't shoot anyone. In fact, Reiter told me that he thought it actually worked better back in the old days because everyone knew what they were supposed to do. Now it's more catch-as-catch-can. Was the guy who just got arrested being protected? If he'd been operating for 30 years, I don't know. At some point, he probably was.

In one form or another, this has been going on in Portland since the Civil War. There are ups and downs, but vice enforcement is always problematic because people want the services, and other people at least have to make a show of opposing them, and so there's always this dance performed by law enforcement. Reiter was worldly enough to know that it was going to happen anyway, and so what you want to do is just keep people from getting hurt.

You can see that school of thought echoed in the current push for drug legalization around the country. Do you see any way that law enforcement and government could reach an agreement where safety is the first priority, rather than making examples of people on the street?

I think that's the way it's headed. One of the really interesting things that's happened, though, is that over the last few decades, government has taken over the operation of some of these vices, starting of course with alcohol, then the lottery — you could go to prison for running numbers here in Oregon 20 years ago — then marijuana, and there are places where [sex work] is legalized, too. What's so interesting is that government takes over and then has their people enforce the tax laws, so we'll be back where we started. Pretty soon marijuana will be legal but cigarettes will be illegal, and all of the people who are enforcing marijuana laws will be enforcing cigarette laws…

It seems like a vicious cycle, but from my perspective now, I can't see Portland ever getting as bad as the ‘70s again, at least in terms of unsolved murders and police cover-up schemes. But maybe I'm just being optimistic.

It's so much easier to see these things 25 years in the rearview mirror because people loosen up, underworld people start talking, a few officials will start talking, and people are less afraid. Are these things still happening in Portland? History tells us they are. They always have. My standard answer to this is: if they aren't, it's either an illusion or it's a miracle.

Pre-order ‘Rose City Vice’ on Amazon.

Follow Patrick Lyons on Twitter.