Modern-day NOLA trumpet player Kermit Ruffins is an outspoken advocate for cannabis’ therapeutic effects on the genre’s musicians. (Image via)

CEO Whitney Beatty knows that the early history of jazz holds weighty significance for the customers who frequent Josephine and Billie’s, her woman-of-color-focused dispensary in LA. She and COO Ebony Andersen named their recently-opened business after femme icons, Josephine Baker and Billie Holiday. The shop is distinguished by marble countertops and jewel-tone painted walls that mimic the ambiance of 1930s teapads, or cannabis speakeasies that were predominantly Black spaces and favored by jazz artists.

Smoky jam sessions took place in teapads after-hours and led to tonal collaborations that came to distinguish jazz, which the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History considers an “important bridge between our nation’s identity, our shared history, and our communities.” For the genre’s Black artists, however, consuming cannabis and other drugs were ways of coping with the era’s overtly racist music industry. The business hardly compensated them fairly for their work, but careers in music were still an upgrade from the limited employment options available to Black people at the time. The relationship between jazz, cannabis, and other drugs is regularly overlooked. But the genre wouldn’t be what it is today without these substances, which helped the early stars channel creativity and survive a discriminatory industry.

“Even though [Baker and Holiday] were persecuted for their cannabis consumption, they used their art to fight against injustice, rejected the mainstream, and wrote their OWN rules — all while making sure to hold the door open for others who would come after,” Beatty writes to MERRY JANE in an email.

This kind of historic reclamation is useful in helping us understand why people use drugs, and how racially-biased prohibition came to be in the US. It’s also key in an etymological sense: The golden age of jazz gave us much of the cannabis lexicon.

Louis Armstrong (Image via)

Satchmo and His Gage

“Jive,” “gage,” “tea,” “mezz,” and “reefer” are terms jazz musicians coined for the plant. “Vipers” was Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong’s favorite slang word for smokers, allegedly because the word recreates a similar-sounding hiss as an exhale of cannabis smoke. The word achieved widespread usage at the time.

Getting stoned was much less expensive than drinking alcohol in the early days of jazz, and cannabis was an ideal fuel for the music’s looping, non-linear melodies. Swing groups toured the country, spreading reefer culture through the nation’s dancehalls. Prior to implementing cannabis prohibition via the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, dancers in these nightlife spaces often smoked joints between songs.

But a man named Harry Anslinger — the first drug czar of the United States, architect of cannabis prohibition (oh, and failed concert pianist in his youth) — famously despised jazz musicians. He was disgusted by the “racial mixing,” particularly romantic couplings, that took place in jazz environments. Anslinger blamed such socializing on the effects of music and drugs. He reveled in a fantasy that involved his Federal Bureau of Narcotics agents arresting jazz greats on drug charges simultaneously in a grand sting operation. Anslinger’s office kept a file on the drug use of artists such as Holiday, Armstrong, Les Brown, Thelonious Monk, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, and many more. On November 14, 1930 (17 years after California became the first state to criminalize cannabis), Armstrong became the first celebrity arrested for weed-related charges after he and his drummer were caught smoking between sets at Sebastian’s Cotton Club in Culver City.

Armstrong spent nine days in jail, but he remained an advocate and consumer of cannabis until he died. “The respect for gage will stay with me forever,” Armstrong said shortly before his death in a 1971 interview with biographer John Chilton, co-author of Louis: The Louis Armstrong Story. “I have every reason to say these words and am proud to say them.”

In Martin Togroff’s book Bop Apocalypse: Jazz, Race, The Beats, And The Drugs, he maps the US government’s depictions of the jazz artist archetype in propaganda as a way to garner support for cannabis prohibition. “If the first image was that of an ax murderer and the second that of a degenerate schoolyard pusher,” he wrote, “the third was equally pernicious and threatening: a Negro jazz musician.”

Billie Holiday (Image via)

Let Lady Live

Most people know about Anslinger’s persecution of jazz’s first lady, Billie Holiday. The iconic singer’s journey went from working in brothels as a pre-teen to stunning international audiences with her perfectly-tuned vocals. She had an on-again, off-again relationship to heroin — and to a lesser extent, cannabis — that became a characteristic of her public persona thanks to Anslinger, who put her consumption of substances on blast. Sadly, her career was limited by drug arrests, particularly after spending a year in jail for heroin use at the height of her popularity. Upon getting out, the police revoked her cabaret license to perform in New York venues that sell alcohol. But even that didn’t stop her; she delivered two triumphant, sold-out shows at Carnegie Hall 10 days after getting out of jail.

Three years later, Lady Day was bed-ridden in a New York City hospital, where she was suffering from addiction-related health conditions. A police officer was stationed in her room and arrested her once again for possession of heroin. Outside the hospital, protests organized by Reverend Eugene Callendar brandished signs reading “Let Lady Live!” Instead, she died on July 17, 1959.

Holiday made no excuses for her drug use, even on her deathbed. In her final interview, published by Confidential Magazine and available in a 2019 collection, she says, “My mother and father never touched dope in their lives — and neither of them lived to be as old as me. I’ve been on and off heroin for 15 years. So who knows? Maybe I needed heroin to live.”

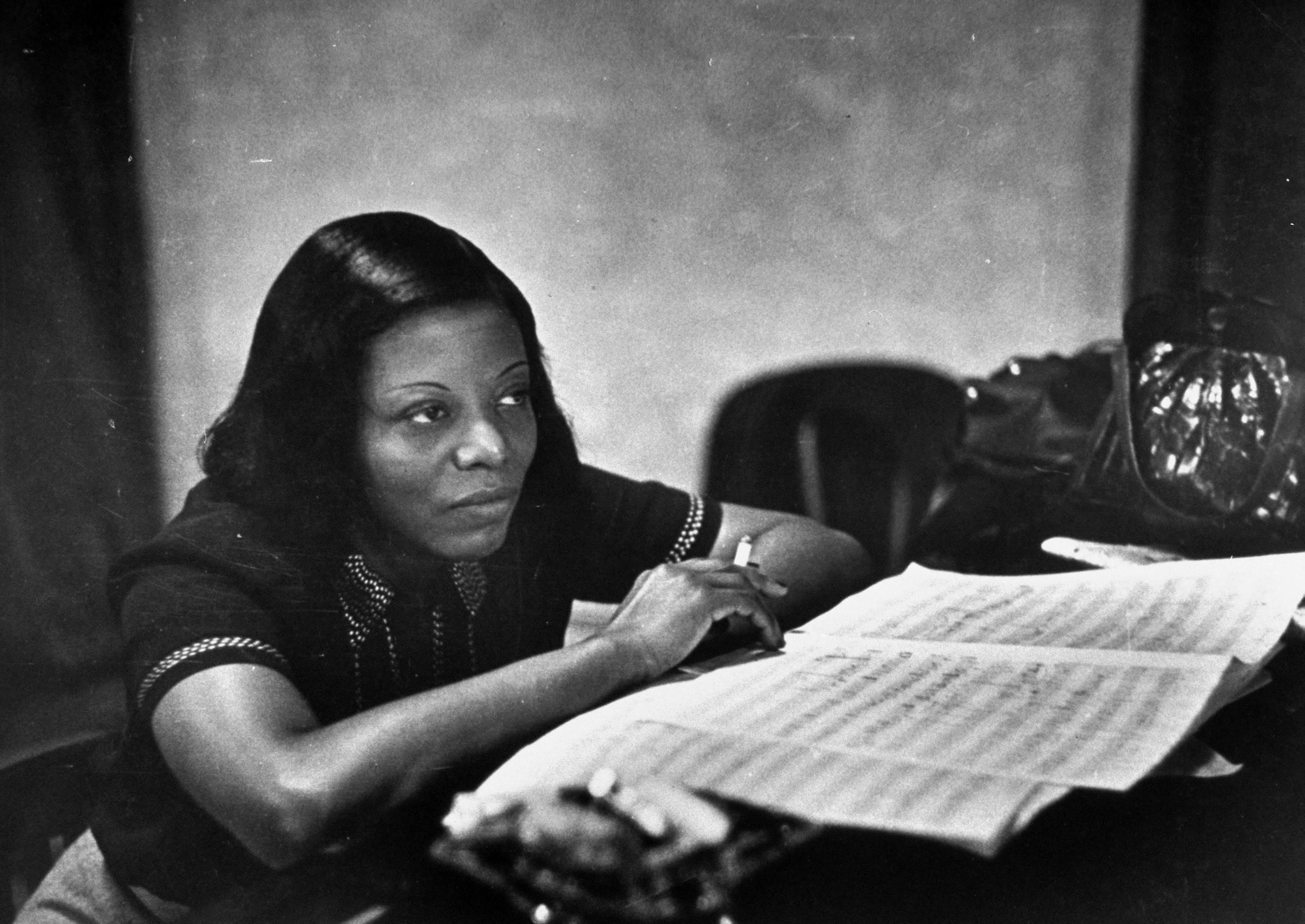

Mary Lou Williams (image via)

Jazz’s Spiritual Dimension

Composer and pianist Mary Lou Williams, perhaps the most celebrated woman jazz musician, was also a habitual cannabis smoker. Although, she mostly used the plant to relax at the end of arduous work nights. She established herself as a formidable artist through astonishing arrangements for Gillespie and Ellington, in addition to performing a heralded residency at Greenwich Village’s Café Society jazz club in the ‘40s. She also hosted epic after-parties that usually went until dawn, often featuring Holiday, Jack Teagarden, and other luminaries exploring the outer reaches of their instruments. While cannabis smoke was a constant, she did not allow hard drug use.

Rather, friends remember Williams all but converting her Hamilton Terrace apartment into a shelter. It was frequently filled with heroin users she knew who were trying to kick their addictions. She spent her life around people with substance use disorder — her sister was an alcoholic and her nephews were heroin users, in addition to what seemed like most of her musician peers. After releasing her magnum opus “Zodiac Suite” — a series of 12 pieces inspired by musical associates of Williams who were born under the respective constellations — her dedication to helping people suffering from addiction morphed into a Catholic reawakening that edged into fanaticism, leading her to ditch music for prayer. In her 60s, she found her way back to sound, composing resounding jazz masses for churches that included New York City’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral. These services often paid homage to Black saint Martin de Porres.

For Williams, caring for drug users wasn’t just the right thing to do, it was deeply connected to her understanding of what jazz was. “It’s suffering that gives jazz its spiritual dimension,” she said in a 1971 interview with Newsweek, as quoted by one of her biographers, Linda Dahl.

Whitney Beatty and Ebony Andersen of Josephine & Billie’s (Courtesy of Josephine & Billie’s)

Reefer Sounds of Today

Josephine and Billie’s teapad in South LA is far from the only cannabis business looking to teach today’s vipers about these smoky legacies. Portland’s Black-owned Green Muse dispensary offers a “green jazz” menu that likens an “airy and expressive” Mango Kush with the music of Thelonious Monk, who was arrested twice in the ‘40s for cannabis possession. Amoeba Music converted the jazz room of its Berkeley location into a dispensary in 2018. In Chicago, Chi High Tours now facilitates three-hour expeditions into the region’s lineage of cannabis and music — from dispensaries to an educational center to Andy’s Jazz Club and Restaurant, a historic jazz hotspot that’s been open since the 1950s.

“At the end of the day, jazz history and cannabis history are just married,” Chi High founder James Gordon tells MERRY JANE. “There was a cannabis revolution. That’s a story that we tell on our tours.”

Modern-day jazz musicians carry on this smoky legacy in their art. New Orleans trumpeter Kermit Ruffins is an outspoken advocate for reefer sounds: “I’m quite sure it was very important to have that joint at the end of the day,” he told Cannabis Now in 2019. “Just going to the neighborhood and rolling a joint, sitting down and smoking and preparing for the next day to make money for your family or make music or what have you.”

This modern-day reclamation of jazz and cannabis history is about more than nostalgia. It serves as an example of how the medicinal use of cannabis often looks “recreational,” and highlights how long the US penal system has used cannabis as a weapon against Black people.

“We are sitting in another age of referendum on racism and injustice,” says Beatty. “Communities of color have been disproportionately disenfranchised by the War on Drugs for years and have had little participation in legalization, despite the heavy price our communities paid. Bringing up the names of these women and acknowledging them is just a small thing we can do to end that erasure.”