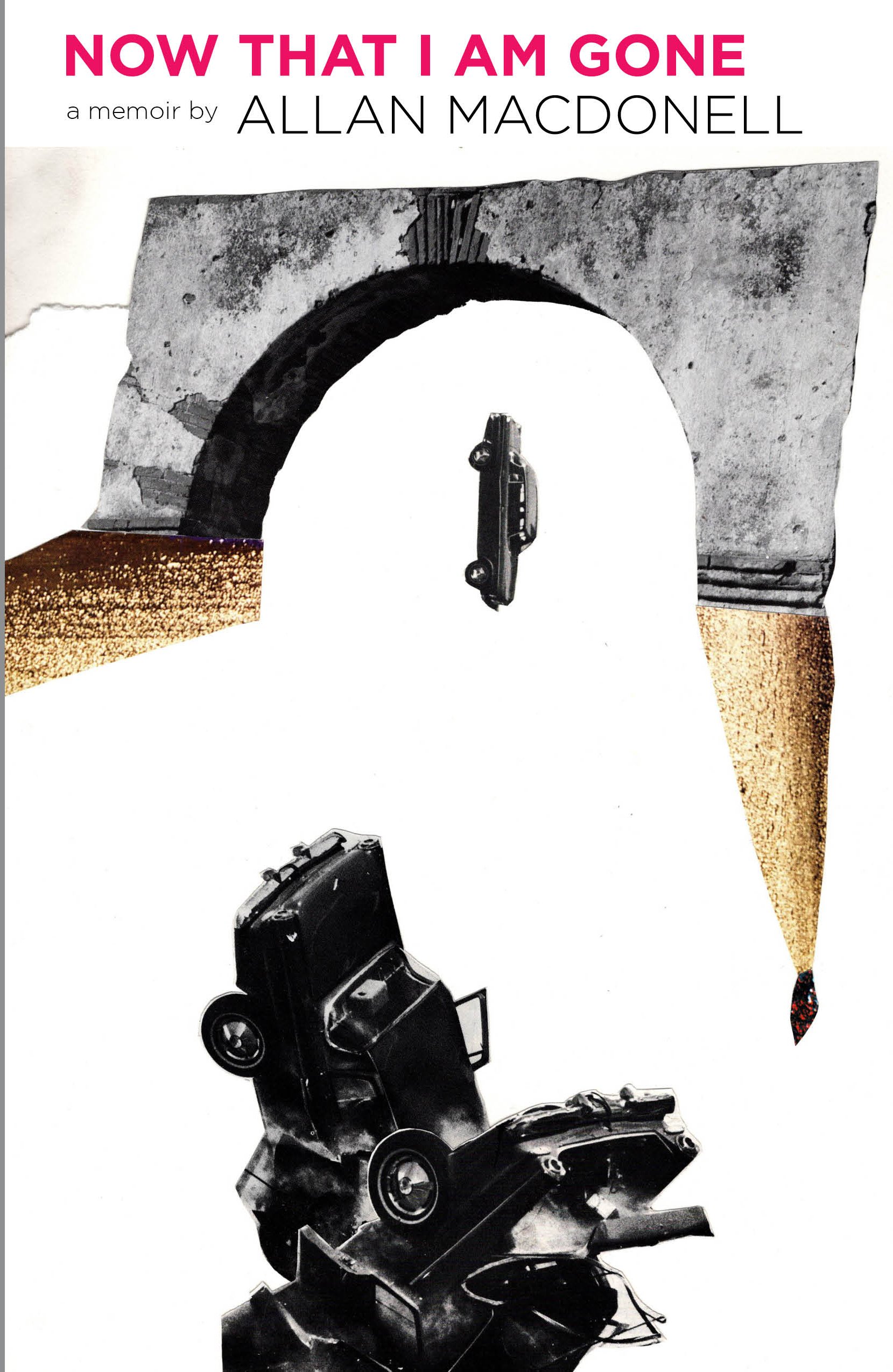

Now That I Am Gone is the latest memoir from long-time Los Angeles counterculture maven, man of letters, and legendary intoxicant enthusiast Allan MacDonell.

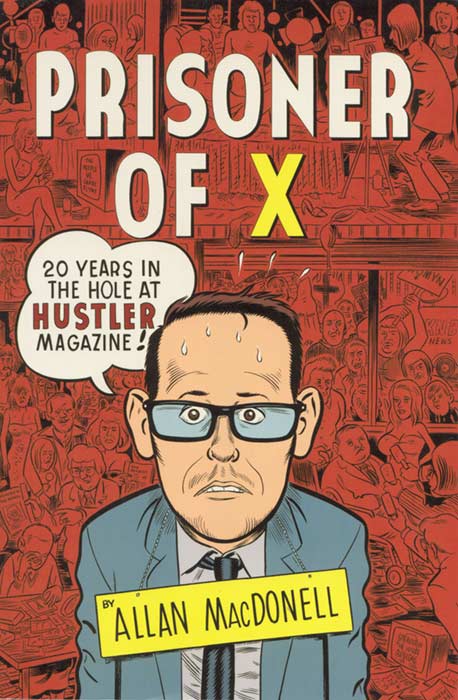

Gone (out now on Rare Bird) follows MacDonell’s first two books, which also looked back on definitive periods of his wild life, as indicated by their very titles — Prisoner of X: Twenty Years in the Hole at Hustler Magazine (Feral House, 2007) and Punk Elegies: True Tales of Death Trip Kids, Wrongful Sex, and Trial by Angel Dust (Rare Bird, 2015).

MacDonell began his full-frontal writing career as “Basho Macko,” a staff member at Slash magazine, the pivotal frontline publication that chronicled the L.A. punk scene at the dawn of Black Flag, X, the Germs, SST Records, and other enduring musical icons.

From there, MacDonell got a copy-editing gig at Larry Flynt Publications, which he powered through to become the reigning Executive Editor of Hustler for decades, overseeing “America’s Magazine” through some of its most controversial and stormy periods. More recently, MacDonell oversaw the editorial of Kindland, a cannabis culture online outpost that burned bright, but has since gone up in smoke.

Now, Allan MacDonell is dead. At least that’s the premise of Now That I Am Gone, an unprecedented memoir in that the author begins by imagining he’s deceased and then looks back on what his existence has added up to, all the while witnessing everything he’s left behind. Suffice to say, Now That I Am Gone is a trip. So is Allan MacDonell. It was a high, heady pleasure for MERRY JANE to talk to him about his latest literary journey.

MERRY JANE: Now That I Am Gone is narrated by you after your death. What actually caused your faux-demise?

Allan MacDonell: There’s two ways to read how the narrator in Now That I Am Gone goes out. The cause of death will be one or the other of these two things, depending on the perspective of the reader. The two chapters at the end of the book play out in two different afterlife scenarios, one that is dreadful and one a person could live with. Which way a reader perceives the narrator dying determines which of these two afterlives the narrator lands in.

Take us through the evolution of this book. Where did the idea begin, how did it develop, and how did you make it finally work?

It started when a friend said I should assemble an anthology book of short pieces by a range of writers on a single topic. So I came up with a topic — death, because sex was already taken — and charted out chapters to assign to various writers. Then, I assigned all the chapters to myself.

When I was a kid, maybe around twenty, I read a novel from 1911 called The Death of a Nobody by a Frenchman named Jules Romains. It was about this guy, a bit of a nobody, who dies, and then the small ripples that go out through the community and the larger world caused by his death. So I did the 100-year update on that, and allowed Mr. Nobody to keep talking after he was dead.

Above, a photo of author Allan MacDonnell

In the book, you write about missing the thrill of taking a drug for the first time. Take us through your first-time experiences with some of the best, starting, of course, with marijuana.

I’d been in a dour mood for a few years, in my early teens. A friend and I bought a lid of ropey green weed at school, rolled up a lumpy crooked joint, and were falling down laughing halfway through the joint. We were literally sprawled on the lawn on our backs laughing at the sky by the time we finished smoking that joint. I pictured laughing myself into a six-pack belly. We were able to maintain long enough to pull some ice cream out of the freezer. Eating ice cream became the funniest thing we had ever done.

Take us through your first acid trip.

This again was in my early teens. Most of these first times will be early teens. With acid, there was a lot of negative propaganda in the 1970s. Our teachers and government told us that taking LSD would scramble our genetic makeup and cause our children to be born with horrible birth defects. We were told LSD could trigger schizophrenia, and there may have been some truth to that one with at least one of my friends. On the other hand, I’d read Timothy Leary and Aldous Huxley writing about the transformative properties of hallucinogens.

I wasn’t old enough to have a driver’s license yet, but I was predisposed, evidently. I was willing to risk malformed offspring and mental illness. Just before I took this ‘orange sunshine’ pill I remember feeling that I was crossing a line, that there might be no coming back to the way I’d been before. In a sense, that’s what happened.

It was strong. It came on slow. There were intense visual disruptions. I became very settled internally, in my emotional core and in my intellectual understanding of what life is, as opposed to what society is, and what my part is in being owned by life and yet still being fully individual and distinctly separate while within society. This is a clumsy way of expressing the validation and wonder of this first acid experience. Physically, it felt semi-orgasmic for the full seven or so hours.

How about your introduction to mushrooms?

This is actually described in the book Now That I Am Gone. This sort of feral girl procured a baggie of super fresh mushrooms to share with my wife and me. This happened in my mid-twenties. We ate the mushrooms cut up in yogurt and drove out to this hiking area in these deep valley hills that are a gateway to the desert where the Manson clan holed up after the Tate and LaBianca murders. The air started to feel sinister. The horizon looked like an approaching dust cloud. The people we met all seemed predatory, opportunistic, and creepy. We had a lot of underlying tensions and resentments and mixed motives in our little grouping of three, and that didn’t play out well with the psilocybin.

There’s a lot of PCP action in your previous book, Punk Elegies. What was your initial bout with angel dust like?

This friend and I didn’t know how much to do so we did too much. We went to the house of this other kid who was in a body cast because he’d fallen off a cliff. His mom kept coming in and staring at my friend and I on the angel dust. She wanted to call an ambulance for us because we couldn’t really talk and my friend was unable to sit upright. It was a spooky experience, and we did the rest of it the next night.

Above, Allan MacDonnell in his 20s

How have drugs and drug culture changed since you first started getting high?

This is kind of a big question that goes off in a lot of directions. I mean just the drop of heroin prices in the Hollywood area of Los Angeles between 1978 and 1985 and the introduction of crack siphoned off a lot of what could be called drug culture, and also created a bunch of addicts who have been funneled into this current rehab culture.

So I guess three big changes from the 1970s would be rehab culture (not so great), creeping normalization of marijuana laws (pretty nice), and expanding medical research among accredited practitioners exploring mental health benefits of drugs like MDMA and psilocybin (pretty great).

You came up through the first wave of Los Angeles punk in the 1970s. How crucial was the role of drugs in that movement and for you personally?

Without alcohol and speed, none of it might have ever happened.

You edited Hustler for 20 years and wrote a great book about that experience. Is there anything more to that story you can add now?

Just how lucky I was to land that job and it’s a shame that the entire genre of intelligent, individualistic, iconoclastic men’s magazines is extinct.

What’s the connection between drugs and pornography?

If you smoke a little weed before jerking off to your favorite visual stimuli, the experience is greatly enhanced.

You were one of the first editors of the cannabis culture site, Kindland. What was that like?

Setting up and running the Kindland editorial was the best job I’ve had since Hustler. The founders were straight talking, paid well, recognized and valued quality content, very enthusiastic. We found great staff writers and an amazing graphic designer.

The weed world is full of fascinating storylines right now: how legality is playing out, the science of the plant, the push-and-pull between old guard growers and new equity investors, all the lifestyle developments, the burgeoning consumer demographics, the anxieties of Big Pharma, the ploys of the drug-testing industry, the music, art and literature components, all the regulatory and finance machinations. Every day presented a string of fascinating story choices. I wouldn’t mind jumping back into that.

Who have been some of your artistic and creative heroes in life, and what role did drugs play in their lives?

I’m kind of anti-hero, but I really liked Edgar Allan Poe, and we know what alcohol did to that unfortunate innovative thought leader. Also, back when I was around 16 or so, I had an inordinate admiration for Lenny Bruce. I still do to this day. It seemed like drugs worked pretty well into Lenny’s shtick, until they didn’t.

Tell us about your current website, The Skeeve.

The Skeeve is a compendium of articles and photo essays that I either wrote myself or commissioned and edited at a few of my previous online editorial positions. So we have a lot of weed-friendly pieces there on The Skeeve. Meaning, if you light yourself up a little, you will find something to enjoy and perhaps even enhance your life’s experience. The Skeeve is currently accepting submissions; so all you writers searching for a good-looking, well-versed platform to showcase your wares, hit us up.

There’s a podcast too, right?

Yes, Skeeveland was started at the suggestion of my publisher, who sees me as in need of extending and defining my individual brand. Each episode is me and one other person, an interesting person who does interesting things, talking at one another as if we are married people stuck in a car together, or something like that. I love doing it. I love talking clever outsider shit with other people who are on the spectrum of otherness and who love talking clever outsider shit.

What’s next for you?

I’m taking bids on a book of short stories called Scary Parts, collaborating on an eight-part comedy-drama miniseries set in the 1970s L.A. punk-rock playpen, tending the pilot-light flames at The Skeeve, and considering all reasonable offers for adventure and/or profit.

“Now That I Am Gone” is out now. Order a copy here, and visit www.theskeeve.com for more of MacDonell’s work.

Follow Mike McPadden on Instagram