The first time I heard the word “slacker,” I was running laps in fourth grade gym class when a particularly sporty classmate of mine took to yelling, “Slackers never prevail!” at kids who chose to walk during the pointless exercise. He was a mean-spirited boy, so the word entered my young vocabulary in the same category as proto-fascist juvenile put-downs like “weird,” “gross,” “nerd,” and “pussy.” (That kid later came out to his Mormon family and they allegedly disowned him, so I admittedly have to cut 10-year-old him some slack, no pun intended.)

I was too young to know it, but I had already lived through Peak Slacker era, a time when many well-to-do, red-blooded types brandished the word at the counterculture similarly to the way that they currently wield “snowflake” and “cuck.” The term “slacker” popped up long before the early 1990s — first as a nickname for Sudanese laborers who protested British overseers with lethargy in the early 20th century, then as a pejorative for American draft-dodgers during the World Wars — but when it poked its head up again in the mid-80s, it found new relevance.

“You’ve got a real attitude problem, McFly. You’re a slacker,” snapped Hill Valley High School principal Gerald Strickland while handing Marty McFly his fourth consecutive tardy slip in an iconic scene from 1985’s Back to the Future. The usage of this word (debatably the first utterance in modern film history) was the first of a few factors presaging a major comeback. The 1987 stock market crash, which effectively erased white-collar job prospects for the college students of Generation X, was another big one. Shockwaves of this economic situation immediately ran, as they always do, through popular culture.

“What Gen X was,” filmmaker Kevin Smith said in a National Geographic documentary about the post-boomer, pre-millennial generation, “[Was] a bunch of us going like, ‘Well, maybe there’s like, a backdoor into this bitch.’” Films like Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (‘89), Wayne’s World (‘92), Singles (‘92), Reality Bites (‘94), Smith’s Clerks (‘94), and of course, Richard Linklater’s Slacker (‘91) helped further define this financially-necessitated, culturally-exaggerated phenomenon.

The kids of the early ‘90s chewed up and spat out utopian ‘60s ideology and openly rejected the go-getter, dress-for-success, Less Than Zero coke-binging, Flock-Of-Seagulls-haircut ‘80s. Drugs were fun, but they weren’t a path to enlightenment or a celebration of success. Clothes were ripped, baggy, and/or second-hand. Music was scuzzy and non-quantized — synthy new wave being the disco to Gen X’s Steve Dahl.

Grunge was the genre most commonly marketed to the SlackerTM, but after it went corporate with Nevermind in 1991, it was chopped liver. A certain subset of the then-burgeoning genre of indie rock, squashed between ‘80s college rock and big-budget “alternative” rock, contained the true essence of slackerdom. The band Superchunk hit the nail on the head with their punky 1989 single “Slack Motherfucker” (sample lyric: “I’m working/But I’m not working for you!”), but the true, album-length pinnacle of slacker rock would arrive three years later on the same label.

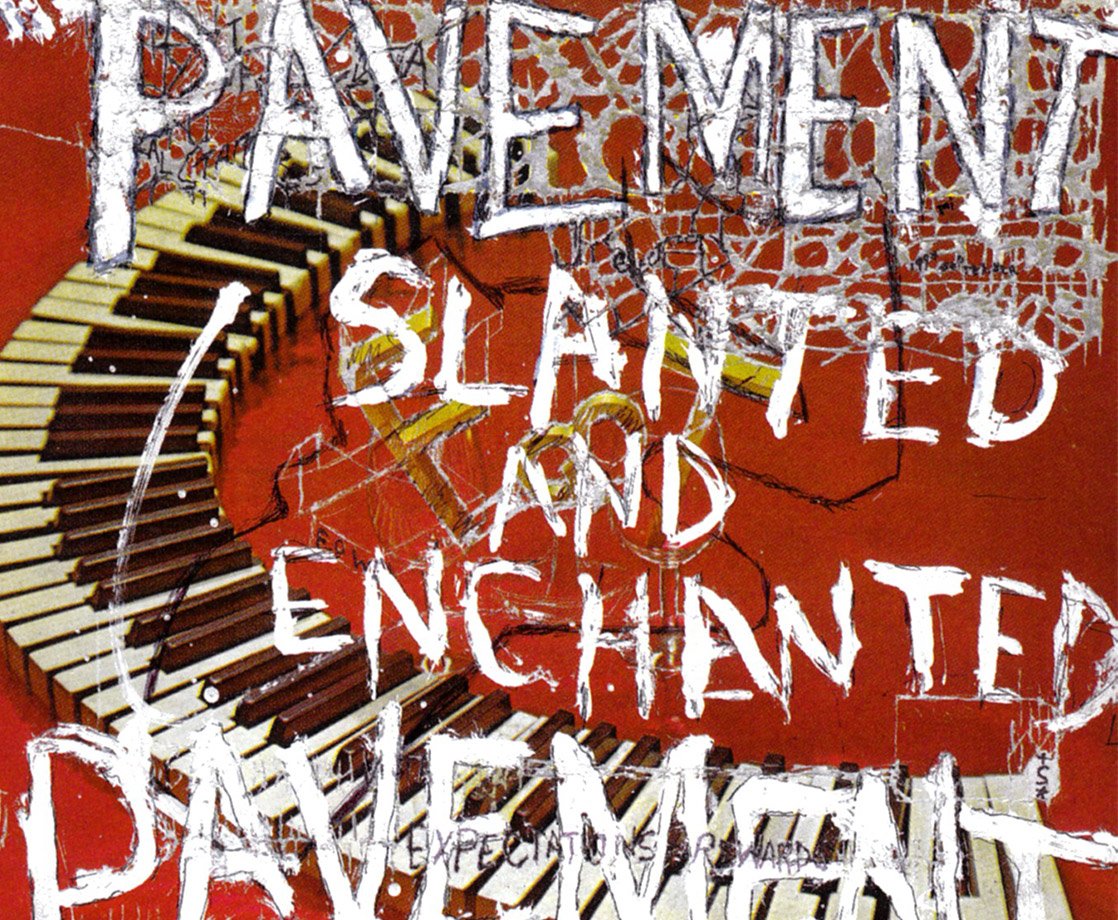

Stockton, California’s Pavement took the slacker torch and ran with it sat on the couch with it. Far from letting the budding lifestyle-cum-genre stagnate or fizzle out, they toyed with it, frontman Stephen Malkmus wetting his finger and seeing how long his erudite poetry could last without burning its way to high art, and drummer/producer Gary Young farting into the flame with his unpolished engineering and production chops yielding miniature solar flares of unrepeatable brilliance. Pavement’s debut album, fittingly released on 4/20/1992, embodied slackerdom in an entirely new way.

Before we get into Slanted and Enchanted’s groundbreaking traits though, let’s stack up each face-value aspect of it that unequivocally defines it as slacker rock. It’s the only Pavement album to feature Young, an aged hippie (13 years older than Malkmus) who ran a makeshift recording studio out of his garage and was fond of doing handstands during Malkmus’ solo songs at Pavement shows. The album’s first lyrics are an ironic reinterpretation of “Ice, Ice Baby.” There is a song wryly named after cottonmouth (“In the Mouth a Desert”), and another that’s a rebuke of a big-time label man (“Fame Throwa”). At one point, Malkmus sings, “Every time I sit around, I find I’m shot.” Matador Records staff have trouble remembering its exact release date. Chuck Klosterman once wrote that the album appealed primarily to “hyperintellectual, underemployed people.” Most importantly, MTV’s Beavis once yelled at one of the band’s music videos, “They need to try harder!”

Perhaps more so than any other rock band, Pavement convinced people that they weren’t trying. It’s why they were pelted with mud at Lollapalooza 1995. It’s why 500,000 people bought their sophomore album off the strength of novelty hit “Cut Your Hair,” and then over 300,000 of them failed to buy the follow-up. It’s why, to this day, music critics put them on blast when they’re reviewing albums by bands that have garnered Pavement comparisons.

While most of Pavement’s peers soared into the mid-90s with big-budget production courtesy of the Nevermind-sparked alternative music gold rush, their sound was more, in the parlance of Buzz Lightyear, falling with style. Speaking to Klosterman on the precipice of Pavement’s comeback tour in 2010, Malkmus called Slanted his band’s best album, saying, “Its flaws are a big part of what makes it good. It's not like some Radiohead record, where the whole thing is good.” Pavement weren’t full-on novice outsiders like The Shaggs, but in the first era when guys playing guitars in plaid shirts was marketable, they may as well have been. Slanted and Enchanted has abrasive, tinny guitar tones, unhinged, wild-man drumming, impenetrable non-sequiturs galore, and one of the most bizarrely entertaining screams in music history on “No Life Singed Her.” While everyone else was taking cues from Mudhoney, Crazy Horse, and Bad Brains, Malkmus and Co. were repackaging post-punk weirdos like The Fall and Swell Maps for American stoners.

Although his famous “I was smoking a lot of grass back then, but to me they sounded like hits” quote was in reference to the band’s third album — the zonked-out and more ambitious Wowee Zowee — Malkmus definitely seems to be in a similar cloud of smoke on Slanted. He finds “Astral rites in dead-end ruts.” He’s “got a heavy coat… filled with rocks and sand,” but if he happens to lose it (sober up), he’ll be “coming back today.” He’s “the only one who laughs/At your jokes when they are so bad.” He’s certainly not the dumb stoner stereotype, more akin to the guy at the party who gets more pompous, but more insightful, after the joint’s passed around.

Somewhat contradictorily to their slacker reputation, Pavement also commonly get pegged as pretentious, perhaps due to Malkmus’ Dylan-on-crack lyrics or fondness for SAT words, or perhaps simply due to their diehard fans telling the band’s many naysayers, “You just don’t get it.” In some ways, Pavement is a secret password to the indie rock club. Few childhood moments made me prouder than when my friend’s older brother (who played in a band and was a hugely influential arbiter of my tweenage music preferences) had his girlfriend over, and she seized my iPod, saw Slanted and Enchanted, and in a shocked tone said, “Oh you like Pavement? You’ve got good taste!” See, I intoned to the imaginary presence of my fourth grade bully, Being a slacker pays off.

But just sit back and listen to Slanted today and I doubt you’ll pick up on either of Pavement’s alleged deadly sins, sloth and pretension. This music has a pulse, unlike say, a good deal of the subdued “surf rock” that came out around 2009/10. The record’s packed with hilarious lyrics, unlike modern-day diarrhea-mouths like Dan Bejar or Father John Misty. It’s also got shit-hot 4/4 beats, unlike any of the math rock that rose up later in the ‘90s. I’m not trying to slight any of those other genres, rather I’m highlighting how the chief aspects that drove people away from Pavement have become far more emphasized in subgenres that arose after the band’s heyday. In short, the naysayers of early ‘90s indie rock had no idea what they were in for.

Today, Pavement have a distinct schlubby-but-intellectual dad charm. Malkmus sounds like your cool uncle after he’s had one too many, or snuck off for a “walk” after dinner. Slanted’s unpolished guitar solos could definitely be emanating from a midlife crisis band’s garage practice space. Hell, Gary Young probably is somebody’s cool uncle at this point.

When I saw Pavement perform at a music festival on their reunion tour seven years ago, it was Malkmus’ birthday, and his wife passed out Cherry Garcia ice cream pops to all of us in the front row. When I saw Malkmus do a few songs at VICE’s 20th anniversary party two-and-a-half years ago, he was wearing a rumpled collared shirt with jeans and covered The Black Crowes’ sleaze rock staple “Remedy,” a song that was just about on the other end of the rock spectrum from Slanted when it also came out in 1992. Pavement isn’t exactly the Grateful Dead, but to indie-minded 40-something devotees and younger onlookers, they might as well be. No other other band has bridged the worlds of high and low art as adeptly in the last quarter century.

We’re currently living in an era that resembles the early ‘90s more than we’d like to admit. The housing market crisis of 2008 is our own personal stock market crash, and the ongoing diminishing of prospects for college graduates has left us with a glut of news media trendpieces on millennials that echo those about slackers from 25 years earlier. Weed, as it was in the early 90s, is popular with young adults again. When researching costumes for a 90s-themed party the other day, my girlfriend remarked, “These all look like outfits people wear today.”

A quarter-century has passed since the release of Slanted and Enchanted, and it’s worth asking: Are we the new generations of slackers? Will we ever prevail? Until our generation produces a slab of slack as gloriously accurate as Pavement did, I don’t think we’ll ever know.

Follow Pat Lyons on Twitter.