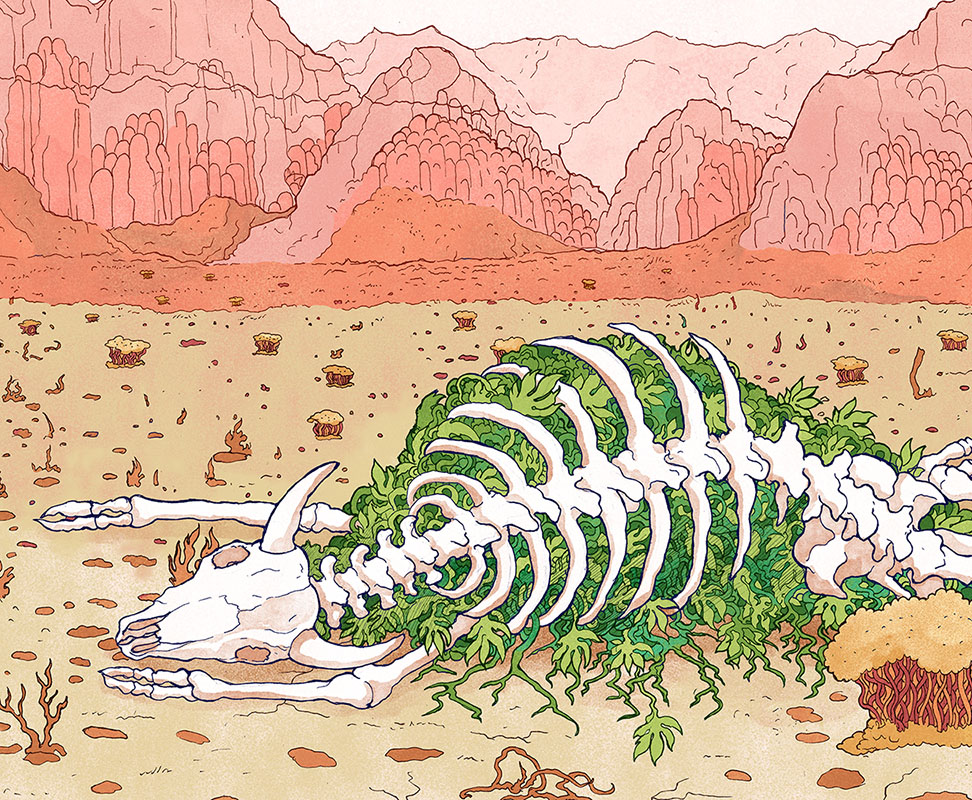

Illustration by Allison Conway

Trent Griffith manages Tsaa Nesunkwa, a headshop on the Ely Shoshone Reservation in Nevada, about 240 miles north of Las Vegas. "Tsaa Nesunkwa," he says, means "to feel good."

Open since 2016, the tribe is ready to convert its headshop into one of Nevada's licensed cannabis dispensaries. The shop already received a tribe-issued dispensary license, approved under a compact with the state of Nevada to grow and sell medical marijuana. And although Griffith sees dollar signs, personal profit isn't his primary motive.

"There's really only one reason I got into this industry, and that's basically for funding," says Griffith. Tax revenue from weed sales, he says, could save his tribe's language.

"It's dying."

The Shoshone language, or Newe Taikwappeh, is "severely endangered" according to UNESCO. Out of the 8,000 Shoshone tribe members nationwide, only 2,000 speak it. Most of those speakers are not fluent, and most of them are over the age of 60. Without educational programs, the language could become extinct within a few generations. Tribal taxes on cannabis sales, Griffith says, could pay for full-time Shoshone language teachers and schools.

And he would know, because he's also the tribe's secretary treasurer.

Griffith, like many Native Americans, is eyeing America's burgeoning cannabis industry to elevate his tribe both culturally and economically. In 2010 (the most recent data available), Nevada's reservations saw a 14 percent unemployment rate compared to that year's national average at 9 percent. Some reservations, such as the Walker River Paiute Reservation, have unemployment rates as high as 80 percent.

Typically, the only stable jobs on reservations are tribal government positions funded by grants from the U.S. federal government, and those positions are few and far between. "A lot of the grants are competitive," Griffith adds. "It's hard to get those funds."

Breaking Down the Numbers

Legal cannabis could create hundreds, if not thousands, of new job opportunities on Nevada's 32 tribal reservations and colonies. In the first month of legalization, Nevada's industry sold $27 million worth of pot, about twice as much as Colorado or Oregon's first months of sales. Currently, there are about 60 medical marijuana dispensaries and 37 recreational stores. These figures don't include other cannabis-related services, although USA Today reports there are "92 cultivation facilities, 65 product manufacturing facilities, 9 testing labs, and 31 distributors."

According to the Nevada Dispensary Association, the state's industry should create over 3,000 full-time jobs by 2020. Colorado's legal industry has already created over 18,000 new jobs, and a report by New Frontier estimates nationwide legalization would generate nearly 300,000 new positions. More jobs mean more profits mean more taxes. But more money can lead to more problems, too.

One of those problems is a man named Jeff Sessions.

Cherry Season

Currently, Nevada's tribes do not operate any dispensaries or cannabis grows on their reservations. The tribes have issued their own dispensary licenses, but so far, none have opened their doors.

When SB 375 — Nevada's tribal marijuana compact bill — became law this summer, it seemed like a dream come true. Headlines clamored that the reservations would become the "next frontier" for weed. Tribal traditions also prefer natural remedies like plant-based medicine over conventional pharmaceuticals. But medical marijuana on Nevada's reservations may be a pipe dream. According to Laurie Thom, the council chair of Nevada's Yerington Paiute Tribe, the feds are saying they'll come after any reservation that grows or sells cannabis.

Several weeks ago, Thom, along with other tribal members and their supporters, met with a law enforcement official from the Department of Interior (DOI)'s Bureau of Indian Affairs regarding the Nevada tribes' medical marijuana programs. Thom says the official told her he "would enforce federal law on Nevada tribes, because the US Attorney General would provide the necessary warrants." In other words, if a tribe were to open a grow op or dispensary, a federal raid could be just around the corner.

"'Don't do it,' he said," recalls Thom.

Although marijuana is legal in the state of Nevada, it remains illegal at the federal level. Jeff Sessions, the US Attorney General and head of the Department of Justice (DOJ), dislikes pot. Last year, he infamously quipped that, "Good people don't smoke marijuana," and just this month, he told a press conference, "I've never felt that we should legalize marijuana." Not even a year into his tenure, Sessions has already shut down several grey-market pot operations (for example, cannabis is legal to possess in Maine, but it's not available for sale quite yet).

The DOJ under President Obama appeared to allow tribal cannabis operations via the Cole and Wilkinson Memos. The Cole Memo outlined rules state marijuana programs needed to follow to appease the federal government's concerns (no selling to kids, no growing on federal property, etc). The Wilkinson Memo clarified the Cole Memo by extending the guidelines to Native American reservations. However, there's a conflict between the memos: the Cole Memo says no pot operations on federal land, yet all reservations fall under federal jurisdiction. Additionally, the memos were just that — mere guidelines. The memos aren't law. Sessions' DOJ can ignore the memos or overturn them at any time.

Furthermore, Sessions' authority comes from an 1831 federal court case, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia. The ruling says the Native American tribes are "domestic dependent nations," on par with the autonomy of state governments. The ruling also made the US government the final arbiter over tribal contracts and negotiations.

According to the Cherokee Nation v. Georgia ruling, the tribes' "relations to the United States resemble that of a ward to his guardian. They look to our Government for protection, rely upon its kindness and its power, appeal to it for relief to their wants, and address the President as their Great Father."

But a year after Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, the US Supreme Court ruled on Worcester v. Georgia, which established the tribes as sovereign nations within the United States.

A series of other court rulings eventually made the reservations "federal trust lands" that fall under the federal government's jurisdiction. Regardless, tribes could always write and pass their own laws, regulate commerce within reservations, levy taxes, and even prosecute tribal members in the tribes' justice systems. Tribal chairs such as Thom contest they also have the right to craft their own weed regulations, issue medical marijuana cards, and grant business licenses to on-site dispensaries — just as U.S. states do.

"[Nevada] Governor Sandoval understands the rights we have as a sovereign nation," says Thom. "He and I are supposed to be at the same level, politically. But the Department of Interior doesn't see it that way."

Joseph Dice, a lobbyist for the Ely Shoshone, joined Thom during the meeting with the DOI. He points to Guam and Puerto Rico as evidence that the federal government is blatantly cherry-picking its enforcement of weed laws. Both Guam and Puerto Rico are U.S. territories, so they fall under federal jurisdiction like the tribes do. Yet, the two territories legalized medical marijuana in 2014 and 2015, respectively. To date, the U.S. government has issued no threats to shut down either Guam or Puerto Rico's cannabis programs.

So why are the DOJ and DOI threatening Nevada's tribes when marijuana legalization could benefit marginalized communities living on the reservations?

The Department of Interior and Bureau of Indian Affairs could not be reached for a response. The Department of Justice wrote back to MERRY JANE in an email stating they would not comment.

Legalities: What About Washington State?

Since the feds are keeping mum on what could be an ongoing investigation, MERRY JANE spoke with Norberto Cisneros, an attorney based in Las Vegas who has represented various tribes for the past 12 years. He confirms that the federal threats relayed by Thom and Dice are real.

"What we're hearing from the federal agencies — the Department of Justice, Bureau of Indian Affairs, the FBI, and the DEA — is they will enforce if the tribes try to open dispensaries, grows, or just retail," says Cisneros, suggesting that federal agents might raid these operations, prosecute participants, seize assets, and ultimately close the tribes' businesses before they have a chance to turn a profit.

Cisneros recognizes the tribes' legal hurdles are incredibly complex — and seemingly selective on the federal government's part. For example, Washington State formed its first marijuana compacts with its own native tribes in 2015, and the feds haven't raided reservations there. Why has federal law enforcement turned a blind eye to Washington's tribes, which have been in the legal weed biz for two years?

"When I've asked them that very question, I've been told two things," says Cisneros. "One is, 'Well, we're looking at them now.' Number two, we've been told about the lack of resources. The amount of resources the BIA has to enforce federal law on federal lands is much less in Washington than it is in Nevada. And I've been told the budget they have for cities like Las Vegas is quite tremendous." The Bureau of Indian Affairs' budget could be used more constructively. For instance, they could arrest, investigate, and prosecute non-Native rapists, who are immune to tribal laws.

Cisneros believes there's a "good likelihood" the feds will follow through on their enforcement threats, but he also believes there are solutions. One solution is revising the Cole Memo's ban on cultivation, possession, and sales of cannabis on federal lands. Another is taking the tribes' pot operations off the reservations and moving them elsewhere in Nevada. Neither solution, he admits, is "perfect." Only sweeping legal reforms at the federal level would solve the problem.

"It's unfair," he says. "And it's a possible Equal Protection violation under the Constitution of the United States."

The Battle at Capitol Hill

Fortunately, the tribes not only have a voice in Nevada's courts, they have a voice in D.C., too. For the most part, Nevada's state assembly supports legal cannabis, and an overwhelming majority of the state's legislators backed SB 375. Dina Titus, who represents Nevada's 1st District in the U.S. House of Representatives, is one of those legislators.

Titus' office recently worked with Dice, Thom, and others to draft a rider for this year's Rohrabacher-Farr amendment, a federal law that blocks the DOJ from using federal funds to prosecute medical marijuana patients and operations that abide by state laws. The rider would have exempted all Native American tribes from federal prosecution for growing and selling weed, so long as the tribes followed their state compacts. There were, unfortunately, hiccups along the way, and the rider died.

Why did the rider fail to move forward this session? Mainly because the GOP-dominated Congress remains pigheaded about pot: a House committee blocked the Rohrabacher-Farr amendment from inclusion in the 2018 federal budget. Without Rohrabacher-Farr, the tribal amendment couldn't be considered either.

"Officially recognized tribes should be afforded protection from undue federal interference in their laws," Titus wrote to MERRY JANE in an e-mail. "As tribes across the nation exert their sovereignty and search for new ways to promote economic development and the prosperity for their people, the Trump Administration should follow the guidance laid out in the Wilkinson Memo."

Titus plans to push the issue again next year, but for now, the Republicans have won.

Footprints Left Behind

Diana Buckner sits on the council for Griffith's tribe, the Ely Shoshone. In past years, she was opposed to marijuana being on the reservations, but has since changed her position after learning about the benefits of medical cannabis.

"The tribal council prior to the one I'm sitting on, and the current council, [have] been supportive of this," Buckner says. "Our tribal community has been supportive of this. I don't see any objection to this from anyone in this area. Except, of course, the Bureau of Indian Affairs" — the people who don't live there.

"We want to do this the proper way, through the state compacts," Buckner continues. "We're just trying to provide this opportunity for our tribes as other individuals have done in other cities. Those businesses provide huge tax opportunities for their cities, and we want to do the same thing."

Beatrice Smithson*, a medical marijuana supporter and a former council member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, echoes Buckner's sentiments. "Why are we being treated differently than the other people that live in the state?" she asks. "That's a discriminatory issue that's going to rear its ugly head."

Both Buckner and Smith say the tribes not only want to regulate their own cannabis industries, they want access to medical marijuana, too. According to the feds, medical pot is banned on Native American reservations, even though cannabis could potentially alleviate their communities' widespread struggles with alcoholism and opioid addiction.

Griffith also sees medical marijuana as a means to improve health on the reservations. "A lot of members have cancer and other pretty bad ailments, and this is the only thing that helps them," he says.

In addition to providing medicine to his people, Griffith plans to form new youth and social programs, as well as cultural events, funded with money made from legal cannabis. These programs could ignite younger tribal members' interest in their tribe, encouraging them to embrace their native roots. On-site cultivation and testing facilities would also provide technical job skills and opportunities that are otherwise only available in metropolitan areas.

Federal intimidation aside, Griffith remains hopeful. "The DOJ and DOI aren't really giving us an answer on what they will and will not do," he says, which creates a looming grey area for Nevada tribes looking to embrace the state's nascent recreational cannabis industry. And, like lawyer Norberto Cisneros suggests, tribes could feasibly fight back by suing the federal government for violating the Equal Protection Clause, under the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. But before it even gets to that, Griffith hints that his tribe may have more power than the federal government lets on.

"A lot of the Shoshone people don't consider the federal government to own this land," he says, citing 1863's Treaty of Ruby Valley. According to the treaty, the Shoshone Tribe are the sole authority over their territory in Nevada. The federal government's numerous failed attempts to purchase the Shoshone reservations lends credence to this claim.

"We could still do anything with our land because our treaty says we never gave any of that away," Griffith says. "It's interesting that they've decided to make this a battleground state."

*Some names have been changed to protect anonymity

Visit Allison Conway's website for more of her illustration work

Follow Randy Robinson on Twitter