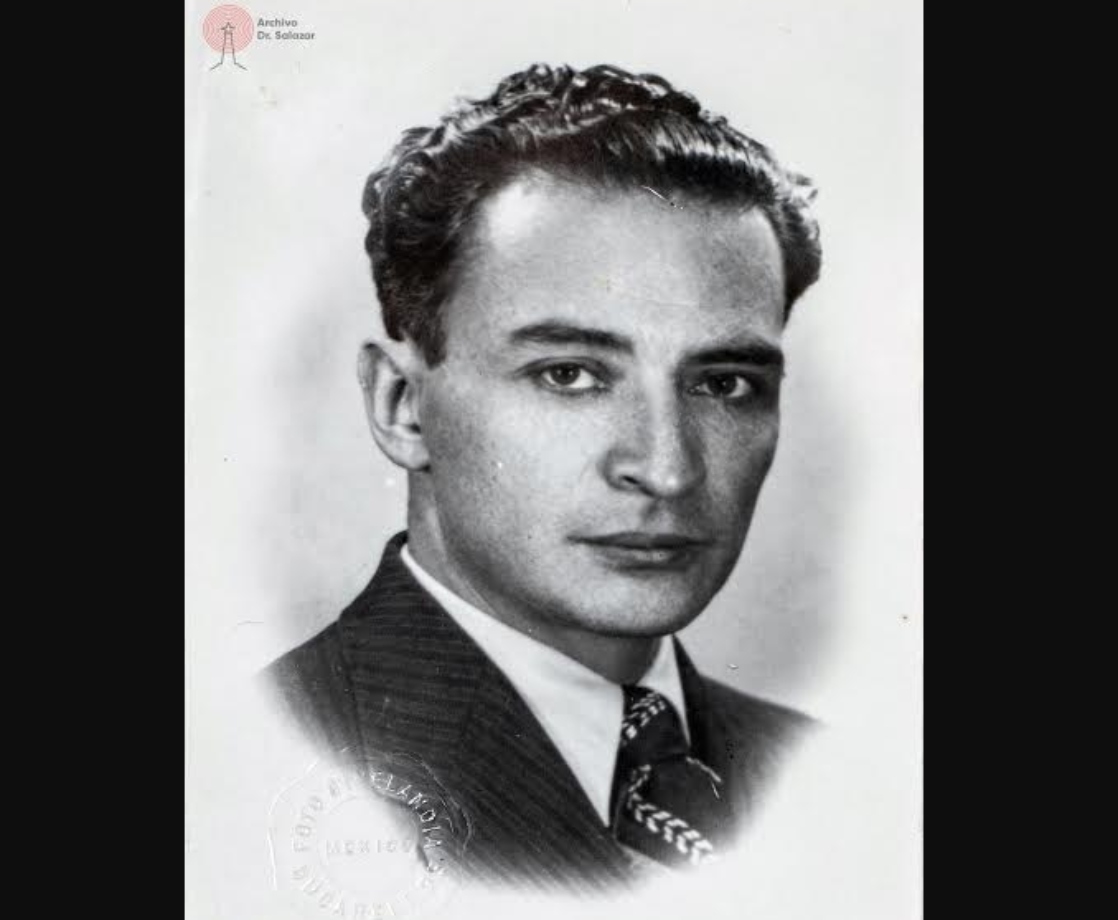

Dr. Leopoldo Salazar Viniegre (Courtesy of Dr. Salazar’s Archive)

The interminable process to legalize cannabis in Mexico often makes it feel like prohibition isn’t going anywhere. But Magali Ocaña Salazar would like to remind everyone of an important bit of nearly-forgotten history: Her grandfather helped legalize all drugs in Mexico — in 1940.

Born in the country’s northern state of Durango, Dr. Leopoldo Salazar Viniegra was a pioneering force in the world’s drug decriminalization and harm reduction movements. Salazar’s work laid the foundation for Mexico’s short-lived drug legalization experiment in 1940. It was terminated when the US government — and infamous anti-drug czar Harry Anslinger — intervened only a few months after the program launched.

Now, Ocaña is on a mission to revive the memory of her grandfather’s legacy.

“I don’t know if it’s due to our people or our government, but someone doesn’t want us to think that we can be autonomous [or] innovative,” Ocaña said. (All interviews for this story were originally conducted on my Spanish language cannabis radio show, Crónica.) “Nowadays people say, ‘We should follow the example of the United States, or Uruguay.’ No! In 1938, these ideas were already being formulated in Mexico.”

Ocaña has taken on the weighty task of creating an accessible digital archive of Salazar’s texts, including the columns he wrote between 1938 and 1957 for the Excelsior and El Universal newspapers under the name of “El Alienista,” or “The Alienist.” She even collects pieces by intrepid historians and writers, such as Froylán Enciso, Nidia Olvera Hernández, and Ricardo Pérez Montfort, who have also helped unearth Salazar’s accomplishments.

Salazar’s story began when he fell in love with the field of psychiatry while studying in Spain and France in the 1920s. Returning home, the man who would eventually be dubbed “the Mexican Freud” by the now-defunct magazine 4to Poder, was appointed director of Mexico City’s Castañeda Asylum, which became known among locals as the “house of madness.”

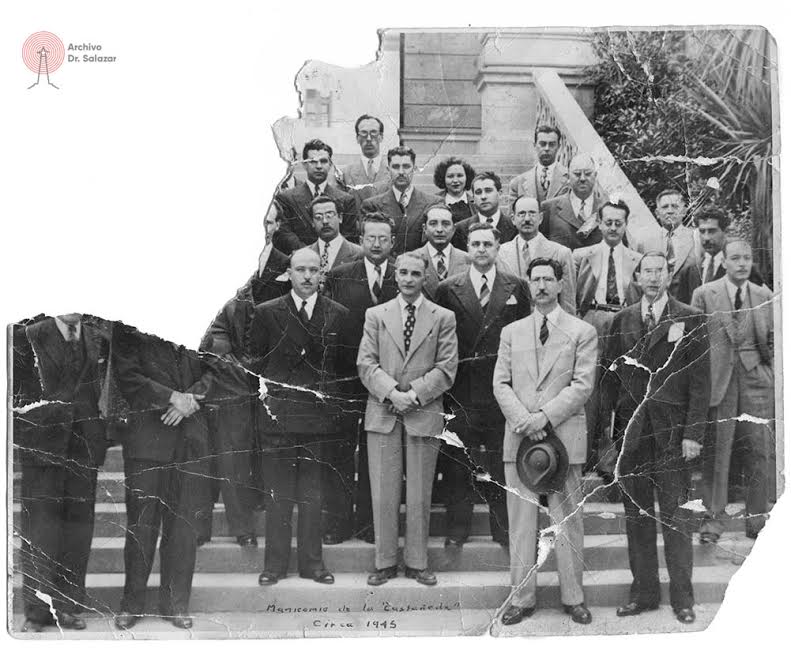

The Salazar family (Courtesy of Dr. Salazar’s Archive)

He lived in one of the doctors’ chalets on-premises for decades with his second wife and three children. The Salazar kids have rosy memories of this odd home. Ocaña’s uncle Leopoldo Jr. told her stories about playing horsey with the country’s first publicized serial killer Goyo Cárdenas, also known as “the strangler of Tacuba.” Cárdenas brutally murdered underage sex workers, but after studying law and music in the mental hospital, was pardoned for his horrific crimes by the president in 1976. The killer eventually became a practicing lawyer and the inspiration for director Alejando Jodorowsky’s film Santa Sangre.

Given the brutal treatment of mental patients in the 1930s, Salazar’s humanist approach was astounding. An official complaint is preserved in the asylum’s records that calls him out for allowing patients to leave hospital grounds on their own recognizance. Ocaña’s family even speaks of him allowing asylum residents to leave the grounds to buy marijuana.

Salazar and his family also hired patients to work for them. His wife, who was a scientist, hired an asylum patient to be her laboratory assistant. Another patient worked as a live-in nanny for their children.

Castañeda Asylum staff in 1945; Dr. Salazar in polka dot tie (Courtesy of Dr. Salazar’s archive)

“His approach towards [drug users], or anyone who was sick, was completely different from the rest of the era,” Ocaña says. “He didn’t do electroshock, he tried to understand the stories of their lives, their addictions, at a scientific level rather than with moral judgments.”

Salazar developed a keen interest in addiction. He was adamant that drug consumers must be treated as patients, not criminals. He believed their well-being depended on the government wresting control of the supply and distribution of illicit substances from abusive drug dealers and corrupt police.

In the case of cannabis, Salazar held that the drug did not provoke criminal or psychotic behaviors, despite the messaging of the era’s widespread propaganda. He wrote a play in 1938 comparing marijuana to a titular, harmless old woman called Doña Juanita. The cover of the published script even included a cheeky tagline, “Inappropriate for decent people.”

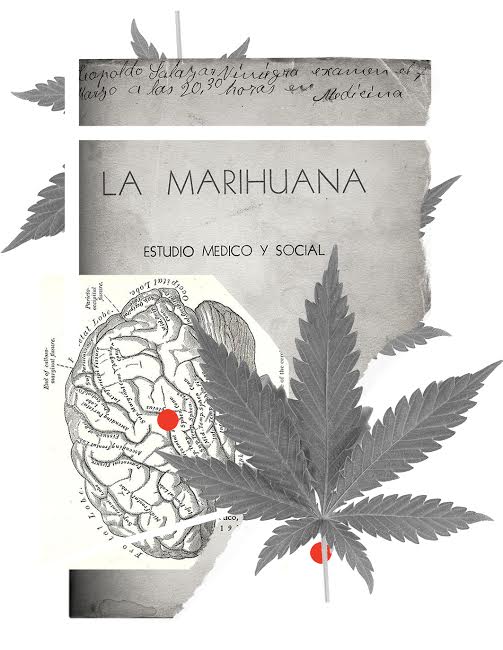

Cover of Salazar’s play “Dona Juanita” in 1938 (Courtesy of Dr. Salazar’s archive)

The play made an impact then and is still relevant today. In fact, Mexican senator Jesusa Rodríguez staged the play in the Senate around the time that legislators were considering cannabis legalization in 2020. But Doña Juanita isn’t Salazar’s only enduring work. He also penned an essay now famous among decriminalization advocates called “El Mito de Marihuana,” or the “Myth of Marijuana.”

Salazar even studied the drug’s effects on his own colleagues to disprove the common misconception that marijuana caused insanity. El Universal reported that Salazar once handed out joints to medical peers at a presentation of “El Mito.”

“My grandfather’s perspective always said, ‘Take marijuana out of this category alongside morphine and heroin,” says Ocaña. “At the scientific level, it’s unviable.”

Salazar was eventually appointed head of the country’s addiction programs — and leader of law enforcement’s battle against drug traffickers — at the federal health department. His archive includes a public letter he wrote to infamous CDMX drug trafficker Lola “La Chata” in which he acknowledges widespread corruption among Mexican police.

In a rare in-depth newspaper interview published in 1938, the doctor proposed a program in which medical professionals would administer drugs to regular users via dispensaries. A year later, his team presented the same plan to the United Nations’ Opium Advisory Committee. The US government ridiculed the program, arguing that it might increase the flow of illegal drugs from Mexico into the United States.

On February 17, 1940, however, President Lázaro Cárdenas’ government made sweeping changes to federal drug regulation, inspired by the work of Salazar and other doctors from the department of health. The new, revolutionary plan would remove criminal penalties for drug use and allow government-operated dispensaries to dose people struggling with addiction (primarily to opiates) with at-cost morphine. (Information is limited on other drugs that were covered under the plan.) The substance addiction wing at Salazar’s mental hospital shut down because this harm-reduction approach gave addicts the opportunity to live relatively normal lives.

“One of my grandfather’s most important theories was, ‘that which is prohibited is the most seductive,’” says Ocaña. “When you stop prohibiting a substance, society begins to think of it in a different way.”

Image by Marina Corach for Dr. Salazar’s archive

But the doctor was ousted from his governmental post before he could oversee the implementation of his ideas. 1940 saw a contentious and violent presidential election in Mexico. Salazar was associated with the opponent of the president’s pick, and was summarily let go before dispensaries opened to the public.

Despite the fact the dispensary program was launched without its primary architect, the sites were popular, according to the limited documentation that survives. One location on Sevilla Street in Juárez, a central Mexico City neighborhood, attracted some 500 patients a day, Froylán Enciso reports in his book titled, Nuestra Historía Narcótica [Our Narcotic History.]

Sadly, the grand experiment was short-lived. A mere four months after the program’s creation, President Cárdenas suspended the regulations on June 7, 1940, blaming WWII-era complications to the supply chain of drugs necessary for stocking the dispensaries.

What actually happened is the US government intervened. Anslinger had telegrams sent to President Cárdenas threatening to cease pharmaceutical exports to Mexico if the country didn’t return to upholding drug prohibition. Cárdenas tried to negotiate; no dice.

The forced end of this brief experiment with drug legalization in Mexico has had very real historical consequences. The country’s resumed War on Drugs would, over time, evolve into a bloody scourge: As of December 2020, official numbers indicate that 79,000 people have disappeared due to cartel-related crimes since 2006. Think of how many people Salazar’s model of legalization could have saved if not dismantled by Anslinger.

After leaving his governmental post, the doctor turned his focus to education, designing and administering an innovative school for kids with behavioral issues called Casa Sin Rejas, or the “House Without Bars,” where students designed their own syllabus. After his death, Salazar’s iconoclastic legacy faded, remembered mainly by dedicated drug legalization advocates, and well-read psychiatry and psychology students.

Ad for “Toxicomanía”

Thankfully, Ocaña has powerful allies to assist in her quest to resuscitate Salazar’s legacy. In April, a star-studded cast and crew launched a fictionalized podcast focused on the doctor’s legalization experiment. Toxicomanía (which translates to “Substance Addiction”) was co-produced by one of Mexico’s most famous actors — the star of Netflix’s first original production in Spanish, Club de Cuervos — Luis Gerardo Méndez, who also plays Dr. Salazar. In the Spanish language series, Anslinger is played by Rainn Wilson, known to many as Dwight Schrute from TV show The Office. Ocaña is listed as its consulting producer.

“I want this series to dilate peoples’ pupils in the best way possible,” says Andres “Ruzo” Vargas, director of Toxicomanía. “Salazar should be part of Mexican lore. He should at least have a street, an avenue, a hospital named after him. Our curiosity about this gave birth to the idea to tell his story.” That intrigue appears to be catching — the show rose to number one on the country’s Spotify podcast charts when it debuted on 4/20, staying in the top slot for two weeks.

Ocaña thinks her grandfather had faith in humankind’s potential for change — and that his ideas could prove useful in an era where many are considering options after the failure of global drug prohibition.

“I think that his work could help people imagine other futures.”