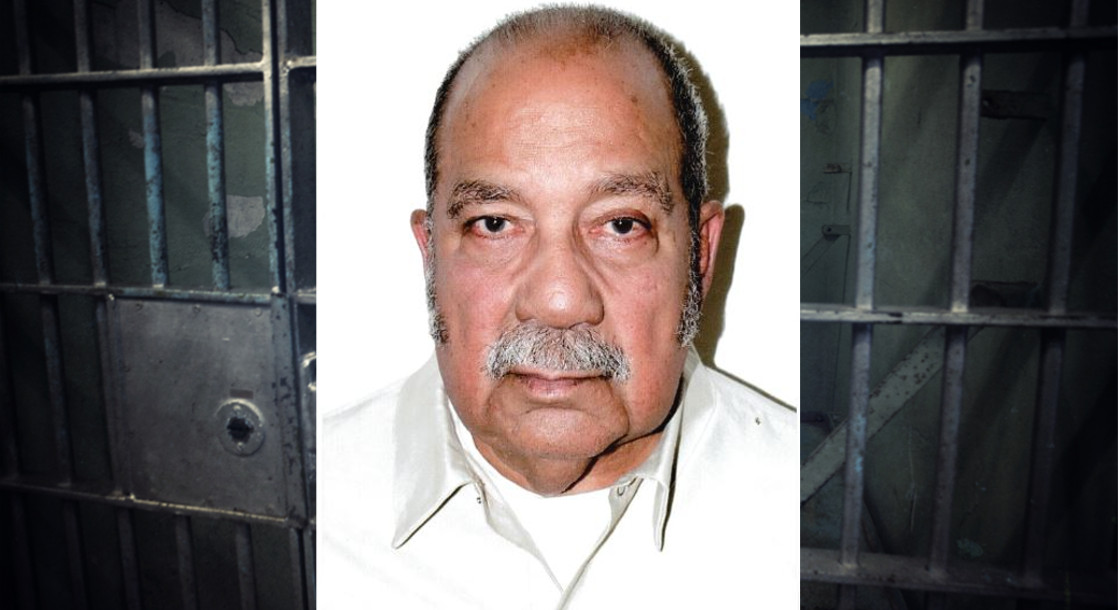

Header photo via CAN-DO

According to the National Center for Health Statistics, the average life expectancy in the United States is 78.8 years old.

Born in 1934, Antonio Bascaro had already beaten the stats when he turned 83 last October. Sadly, however, he’s spent nearly half of his life behind bars for smuggling marijuana, making him the longest-serving federal inmate doing time on charges for cannabis.

With nearly four decades of prison under his belt, a weakening ability to walk, but a mighty will to live, his story and circumstances stand out as particularly compelling, and quite frankly, heartbreaking. Bascaro is an example of someone who has slipped through the cracks; a case deserving of attention and investigation into the lack of empathy and compassion that seem to be the undercurrent of the criminal justice system. While his effective life sentence for transporting a plant that’s increasingly legal continues to be funded by taxpayer dollars, is this something we, the people, actually find acceptable?

While getting to know many incarcerated “marijuana lifers” through researching and writing MERRY JANE’s new docuseries Prisoners of Prohibition, I came to know of Antonio, or Tony. The four-part series is an effort to humanize people serving time for marijuana; however I think Antonio’s story is so tragic, it speaks for itself.

In the late 1970s, Bascaro was charged as a member of a trafficking operation moving marijuana — 600,000 pounds, to be exact — from Colombia to Florida using fishing boats.

Court records mention Antonio Bascaro, Manuel Villanueva, and Jose Acosta as the ringleaders; however Antonio maintains Acosta was actually the sole owner and leader of the group. Bascaro says he never physically touched any cannabis, focusing mainly on administration and occasionally observing the unloading of shipments.

Nevertheless, all three men were wiretapped by government agents, arrested, and eventually went to trial. While Acosta and others offered information in exchange for reduced sentencing, Bascaro refused to testify against his co-conspirators.

“I didn't take the stand to testify in my favor, because I'll not testify against any others to save myself,” said Bascaro.

Frustrated that Bascaro — a Cuban exile who worked with the CIA as a pilot during the Cold War’s Bay of Pigs invasion — would not cooperate, the court held him in contempt and sent him to spend 16 months in jail. For his cannabis “crimes,” Bascaro was ultimately sentenced to 60 years in prison without the option for parole.

Meanwhile, Acosta was released in 1994 for the same offense.

Bascaro has repeatedly applied for a reduction of his sentence, only to receive multiple denials without explanation. And despite his dwindling health, he is seemingly ineligible for compassionate release.

The 1984 Sentencing Reform Act set in place a compassionate release program to allow the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to reduce sentences of federal prisoners for extraordinary reasons like terminal or age-related illness. However, the BOP is responsible for seeking a person’s release themselves, and has been oddly selective in determining who meets criteria and is actually eligible for release.

Aicha and Antonio Bascaro; screenshot via Prisoners of Prohibition

According to FAMM, or Families Against Mandatory Minimums, the BOP brings only a small amount of these release motions to court annually — on average about two dozen. Meanwhile, the delays that plague the program often result in a prisoner’s death as they await a decision.

For Antonio, not meeting the BOP’s inscrutable compassionate release requirements unfortunately means that the first-time, nonviolent marijuana offender and father of three has been condemned to waste away in prison until his scheduled mandatory release day.

“Thank God, my mind and spirit are under control, although my physical condition is poor, I think will survive the year that I still have to do before going home on my mandatory release day,” said Bascaro, whose release from incarceration is slated for the summer of 2019.

In the meantime, Antonio’s health is deteriorating. After a ten-hour surgery on his lower spine and three days in the intensive care unit, he now gets around primarily in a wheelchair, using a walking cane for short distances. While he waits to be reunited with his children, he spends his days reading, listening to the news, and speaking with his family, who yearn for his return.

“He disappeared from my life when I was 12 years old. My children barely know him and mostly [do] through photos. They will never know what an amazing grandfather they have,” said Antonio’s daughter, Aicha.

A family torn apart by draconian cannabis laws, left to toil as time ticks away, cannot morally coexist in a country with a president who says he’ll consider a bill to let states legalize marijuana as they see fit; not to mention the injustice of the federal government continuing to imprison a man — who previously helped that same institution with its anti-Communist dirty work — for transporting a plant now legal in over 30 U.S. states.

Though recent signals from Congress and the Trump administration show that hope for real reform is on the horizon, it could be too late for Antonio. Cannabis legalization, and retroactive justice for prisoners of America’s outdated war on weed, is needed NOW. Read the full text of our latest letters from Antonio below, then check out how you can help prisoners like Tony Bascaro attain the freedom they so desperately deserve.

Hi Brooke:

Thanks for your interest in my personal case. I'll follow with the answer to your questions.

I was kidnapped by the U.S. Embassy, Interpol, and Guatemalan personnel, without extradition proceedings, on February 21, 1980, from my house in Guatemala. I was brought to Florida, on scheduled flight of Pan Am #504 direct to Miami.

I was tried and convicted in Savannah, Georgia in 1980, and sentenced to 10 years.

After that trial, I was summoned to testify in front of a grand jury in Pensacola, Florida. When I refused to testify, I was put in contempt of court, and was under pressure from the Assistant U.S. Attorney to do so until 1981, when the main target of that grand jury decided to cooperate and help build an indictment.

We were tried and convicted in 1982. I didn't take the stand to testify in my favor, because I'll not testify against any others to save myself. I was found guilty, and sentenced to 60 years under U.S. Code 848, with no parole and consecutive to the prior sentence of the same conspiracy. That day, my family was partially destroyed, and my life and my previous work of many years disappeared and went into limbo.

It’s hard to see, that after so many years incarcerated, something positive come [like marijuana legalization] that could be helpful to my return to my family. Although it won’t help me, it will help many others that still have a long sentence to go.

My daily routine: I wake up at 5:30 am, take a pain pill and wait for it to become active, then, I make my bed and prepare my coffee, which helps the pill work better. Then when I feel better, I use the commode, and take a shower and shave. Then I prepare some breakfast from my commissary items and eat it in my cell. After that, I listen to the news and read my correspondence from my family and friends. Then I go with my walker to the computer room to check my email. After I complete that, I return to my cell, to read and listen to news and music. At lunchtime, I prepare something to eat from my commissary items, check my emails, and come back to my routine. After count time, at dinner time, I cook my meal again, and watch TV for a while, to see the news and some programs that I like, and after checking my emails, go to bed.

You may ask yourself why I eat in my unit, and the reason is that because the new warden made a new rule to move in the compound that hurt my medical condition. As we have a lake in the middle of the compound, he order to walk counterclockwise around it, and that makes me walk an excessive distance. Although I talked to him, he said to check with the health service, and they did nothing. So that is why I decide to eat in my unit, to avoid the struggle and the pain.

I'm a walking miracle. At 80 years of age, I survived over 10 hours of surgery in my lumbar area, that kept me three days in intensive care on blood transfusions, and over one month in the hospital. I have a wheelchair to move around and a walking cane for short distances. I stay most of my time in the unit. The living facility is average, but the health service is very slow and insufficient. Outside [medical] appointments are difficult, and take too much time to accomplish.

Thank God my mind and spirit are under control. Although my physical condition is poor, I think will survive the year that I still have to do before going home on my mandatory release day.

Thank God my family relations are superb, especially with my kids and grandkids. Thanks to the work of their mother, all of them are professionals, and their families are [accomplished].

I applied for reduction of my sentence twice, and both were denied by former President Obama. I also made many motions to the court; the answer: "Denied, No Opinion, Do Not Publish." Nobody knows the reason why, and the same thing happened with my application for compassionate release. Sincerely, I don't expect anything before my mandatory release day in June of next year.

In the 38+ years that I have been in the system, I have seen and lived through so many situations, enough to make a good-sized book.

I do authorize Merry Jane to use this information for anything that may be positive for my return to my family. Thanks again for your interest in my personal situation.

Sincerely,

Tony

Next, see Antonio’s latest letter to the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Justice, requesting that he receive fair treatment in his plea for freedom:

So what can you do to help Antonio reunite with his family and receive the proper medical care he urgently needs? Sign this petition calling on President Trump to grant clemency to Antonio Bascaro and finally liberate him from unnecessary incarceration.

And to learn more about the plight of America’s pot prisoners and what you can do to help, visit our homepage for Prisoners of Prohibition, watch the series, and please spread the word! For even more info and ways to join the fight for cannabis justice, we highly encourage you to visit the website of CAN-DO, a nonprofit advocating for clemency for all nonviolent drug offenders. It’s time for all of us to stand up for our rights!