A poet named Fred Durst once wrote, "Everything is fucked, everybody sucks." And that's about how it feels to be living in America right now. I'm writing this from my house in Durham, North Carolina, where not two miles from me a group of 200 or so people from all walks of life are waiting to counter-protest against members of the KKK, who have announced a march against the removal of a Confederate monument at the local courthouse. Whether or not they actually show is up in the air––white supremacists are driven by fear of "the other," after all, so they have a habit of being too scared to show up to their own demonstrations simply because people might oppose them––but if they do, there's no doubt that they'll be so overwhelmed by the sheer number of human bodies standing up to them and be forced to stand down. Durham is unfortunately not a unique case: last weekend's clash in Charlottesville between white supremacists and those who oppose them seems to have sparked a wave of similar protests around the country, a fire that's been eagerly fanned by President Trump's own racism (or his stupidity, or both).

Right now, it's impossible to tell whether or not this uptick in racist demonstrations––which will uniformly be met by massive counter-protests––is the last gasp of a dying ideology, or a sign of something more ominous on the horizon. Donald Trump has emboldened white supremacists around the nation, and as Trump's car crash of a presidency grinds itself into the ground, the far right will be the only base of support he has left. When he (hopefully) leaves the White House in the dead of night, resigning from office and retreating to an island where he can watch CNN and type tweets into a special phone that's not actually connected to the internet, will white supremacists fuck right off along with him? We can only hope so. The problem, of course, is that the internet has made atoms of information as common as words were a hundred years ago, and now more than ever it's possible to assemble that information in a way that completely reinforces your worldview while isolating you from everything that's going on around you. It's entirely possible that this wave of emboldened white supremacists is locked in an internet-abetted echo chamber of reinforcement and has no idea they're losing relevance with every action, every statement, and every day. This is why when they do venture out into the real world, it's important to show them how unwelcome they are.

In today's edition of Bongreads of the week, we'll be discussing some of pieces of writing that dissect the events and characters who led us to our unfortunate state of information overload.

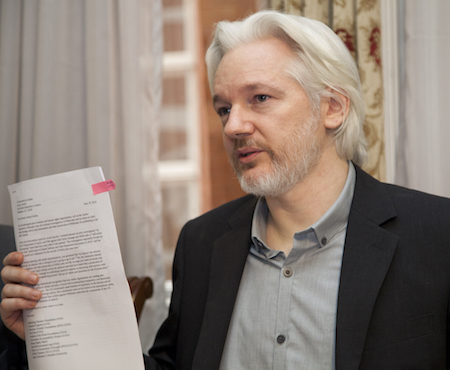

Julian Assange: A Man Without a Country

Raffi Khatchadourian for The New Yorker

Let's start with Raffi Khatchadourian's fantastic recent profile of Julian Assange, who's of course the founder of Wikileaks and who may or may not have a hand in tipping our recent Presidential election to Donald Trump. As Khatchadourian's recent piece makes clear, it's pretty damn hard to tell whether or not Assange's ethos of radical transparency comes from a place of wanting to speak truth to power, or so that he can tear down those in power and take their place. Either way, Assange has a maniacal ego, loves attention, and routinely lies through his teeth, which makes him an ideal profile subject. Khatchadourian offers a sense of the persona Assange aims to present, and then using canny reporting to tear that persona down, filling the void with unanswered questions.

The Satoshi Affair

Andrew O'Hagan for The London Review of Books

While Julian Assange and Wikileaks seem to be working towards the erosion of privacy as we know it, Satoshi Nakamoto, the founder of the internet cryptocurrency Bitcoin, is driven by almost the exact opposite impulse. After publishing a white paper laying out exactly how an online currency based around anonymity might work––and then proving his point by creating it––the pseudonymous Nakamoto became a ghost. Centered around a man who claims to be Satoshi himself, O'Hagan's piece is as informative as a history textbook and paced like a thriller. In the end, we never quite find out exactly who Satoshi Nakamoto is, but in the end it matters less than the knowledge that on the internet, nothing is as it seems.

(Note: O'Hagan's piece is 35,000 words long and you'll have to give the London Review of Books to read the whole thing, but trust me when I say it's worth it.)

Google Doesn't Want What's Best for Us

Jonathan Taplin for The New York Times Sunday Review

If the internet were a real place, Google would be the entity that built our roads and sent our mail. They'd also be a branch of the government, and they would exist only to help us get places and talk to each other. But since the internet is online, Google is a private company whose goal is to make money. This allows them the ability––as well as the incentive––to control which websites we find and to monitor our online communications, learning intimate details of our personal lives so that they can sell them to other private companies. For the most part, if Google doesn't control something, then Facebook does, and together, these two companies have a tremendous amount of power over everyone in America, and since they dominate their markets, there's nothing we can really do about it. If you weren't mad as hell about all of this before reading Jonathan Taplin's essay digging into the implications of Google's internet hegemony, you will be afterwards.