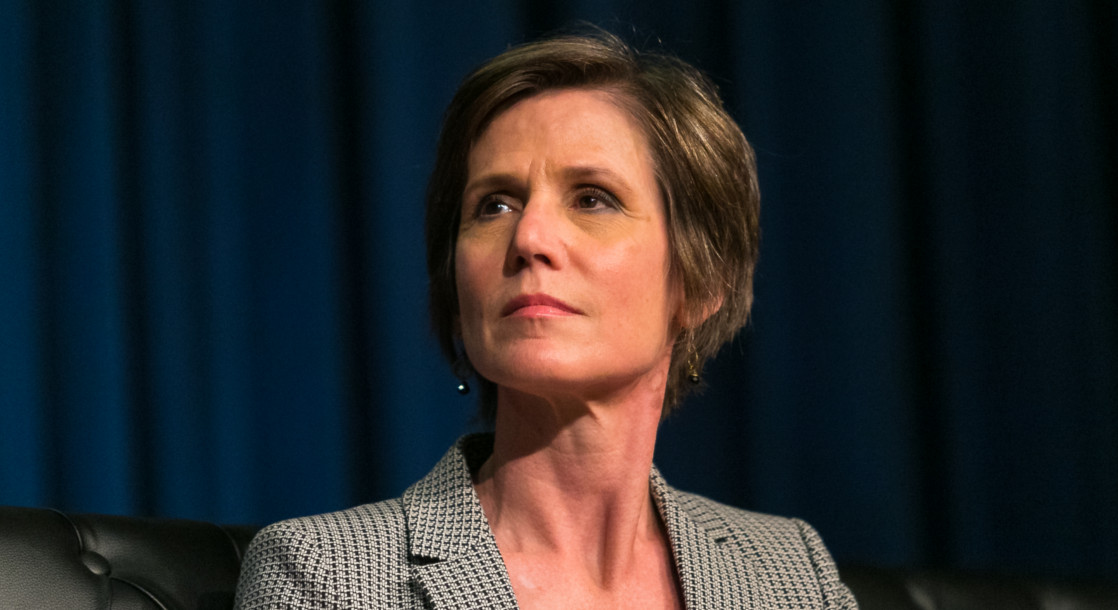

All photos courtesy of David Wienir

Billed on its cover as “An American’s journey into the Red Light District,” David Wienir’s new book Amsterdam Exposed isn’t quite the investigative research text you’d initially expect. First embarking on the project as a graduate student studying in Amsterdam in 1999, Wienir envisioned interviewing as many of the famed district’s sex workers as he could, creating a well-rounded look at an underreported, misunderstood population. That’s not exactly what came to pass.

Finally published 19 years later, Amsterdam Exposed is instead more of a memoir. Wienir struck out on his initial mission on nearly all accounts, struggling mightily to find a single working girl who’d give him the time of day, let alone detailed answers to his questions. The one exception, a Dutch girl named Emma, proved to be a challenging enough subject, with Wienir pursuing her for an interview for the vast majority of his initial four-month stay in the Netherlands.

What stands in for a diversified look at legalized sex work is an engrossing coming-of-age tale about a straight-and-narrow Ivy Leaguer finding himself amid the so-called “vices” of Amsterdam, as well as an unconventional love story. Allowed the freedom to write a more narrative-focused book, Wienir conjures up vivid images of a magical city, and accurately conveys the confusing ennui of young adulthood, despite now being 45.

Upon leaving Amsterdam days before the turn of the millenium, Wienir graduated from Berkeley Law and has since become a prominent entertainment lawyer, which no doubt delayed the release of Amsterdam Exposed. He’s now married to Dr. Dina, the cannabis entrepreneur (and friend of MERRY JANE) who was the inspiration for Nancy Botwin on the show Weeds, which also gives him an interesting perspective on Amsterdam’s other major tourist draw. As Wienir himself tells it, it took quite a while to reach a place in his buttoned-down career where he’s comfortable sharing his long-in-the-works Red Light District project.

MERRY JANE caught up with Wienir over the phone to talk about Amsterdam Exposed’s long gestation period, the changing face of the District, and the Netherlands’ recent crackdowns on cannabis culture.

MERRY JANE: From the time you left Amsterdam in '99 to the actual publishing date of the book, how much did your vision or rough idea for Amsterdam Exposed change?

David Wienir: It's changed quite a bit, and that was one of the reasons it took me so long to be ready to share [the book] with the world. One of the things that I really struggled with is that after the events of the book, I launched right into corporate America. I started off working at a very old international law firm, which had been around for 150 years, and then I worked at two of the top talent boutiques [in L.A.]. I was very much in a world where writing a book like this wouldn't have been accepted.

Because of that, when I was writing the book, I was really afraid to put myself in it. I think one of the things — I'm sure you saw when you read it — is that it's as much of a coming of age story about me as it is about Amsterdam. It wasn’t until I got married and was working over at a talent agency where I had a bit more breathing room that I was able to get some more perspective and really be honest with myself and my feelings. I got the confidence to put myself in the book, which is one of the things that the early drafts were really missing.

Ultimately, through a lot of soul searching and really trying to dive deep into my feelings, we got the product that we have now. Lawyers aren't really trained to share their feelings. We're trained to have emotions and feelings and put them all in a box and lock them up somewhere. It was quite an exciting process for me to emotionally, from a growth perspective, really reflect on my journey in life. I think a lot of that showed up in the book itself.

Definitely. So the earlier drafts of the book, were you using third-person POV or something? Were you doing more of a research-based, secondary source-heavy type of thing?

No, it was never meant to be a research book. Having gone through academia most of my young life, I intentionally didn't want it to be that. On Goodreads, one of the people who didn't love the book said that I needed more statistical research. And, I'm like, That's not what the book's about. The book's about trying to take readers on a journey they couldn't otherwise go on themselves, and ultimately let them come to their own conclusions. I really tried to be as nonjudgmental in the process as I could.

As much as the book is about [the sex worker] Emma breaking free, it was about me breaking free, too. I’ve talked to my wife about this — I think if it wasn't for this book, we might never have found each other and might never have gotten married. When I met Dina, it was back in 2007 and she'd already been in the [cannabis] business about five years. I was, at the time, representing Steven Spielberg at one of the oldest, most stifling, conservative talent agencies, and there she is running a dispensary in a doctor's office.

In the book, I’m coming to terms with not getting pigeonholed in life, just like the women who work in the [Red Light] District. We all love to label — not just other people, but ourselves, too. If there's any real conclusion that I tried to reach in the book it was that the labels we place on others and even ourselves can really be unfortunate and limiting. They can prevent one from going on the journey that they're meant to go on.

So when you were striving to make this more of a level-handed, unbiased look at the Red Light District, did you find yourself having to alter some of the thoughts you actually had back in the day?

The thing that's restricting is that the events took place when I was 26, but I ended up publishing it when I was 45. I really wanted to keep that youthful naivete that I had when I was 26, but while using it, obviously keep the perspective that I have as a man who is much older. Also, it was a very different era. It was not a politically correct era. So I was trying to take readers back to that time while also not unnecessarily offending them. But it's certainly not a sanitized book, either. Writing a book like this was like threading a needle and trying to take you through this world, exposing you to it, but keeping you engaged and not letting the reader get to a point where they're turned off and they stop reading.

Do you think that if you had better luck interviewing more girls in the District it would be a vastly different book?

It's hard to say. I think the book is really more of an unconventional love story than anything else. And it's interesting, when I was just back in Amsterdam about six weeks ago for a book signing, I really wasn't intending on spending much time in the District and speaking to the women, because obviously I knew they were there to work. But one day I was walking through and a woman called me over and she wanted me to come in and I said, No, actually I'm here because I just wrote a book about the place. And her eyes lit up and she wanted to go get a copy. So I ended up running back to my room and getting her a copy and luckily she was still there. I was surprised that a woman working the District now would be interested in reading a book about this from an American perspective.

So I ended up spending the next couple of days going around the District with a whole bunch of copies, presenting the book to about twenty women working there. A lot of them were very excited, a couple of them cheered up a bit, brought me into their rooms, we talked a bit, and I heard some of their stories.

When you went back recently — I know you probably didn't spend as much time as you did when writing this book — but did you sense that women were less afraid of talking about their careers, or even just giving you the time of day if you weren't a paying customer?

The world's changed so much and going back 18 years later was shocking in many respects. I think people are generally a bit more open to talking about themselves than they were in 1999, when privacy was a much different thing. But the Red Light District's changed, too. Back in ‘99 there were 520 windows, and now there are less than 380 in the District. I mentioned this at the beginning of the book: Amsterdam Exposed talks about a world that might soon be gone. Amsterdam is trying to re-district it out of the center of town and bring in boutiques. There are literally arcades and fancy clothing stores in these exact spots where women have stood and worked for decades. So it's changed. You used to walk in the District and literally be in a different world.

What's happened recently is the amount of tourism has exploded, as has the amount of abuse that the women take on a day-to-day basis. People forget they're human, even more so as the world's opened up a bit. That was hard to see. You don't have to condone the choices these women have made, but they are people. On the internet, people think they can say whatever they want, tweet whatever they want, that they're removed. People in Amsterdam are going to walk around the District as a tourist and have the same mentality: Oh, there's a piece of glass between us, so I can make whatever offensive comment I want.

What are the most common misconceptions about the Red Light District?

People are very quick to romanticize it and I think it's because when you go there it seems a bit like a theme park. Most of the women I came across [in 1999] were European, and there were certainly a lot of Dutch. When I went back there weren't really any Dutch women at all, and just about all the women were Bulgarian or Romanian, which leads me up to the big question of are these women working there on their own volition? Is it about trafficking? Are they making their own choices? And, of course, that's a big issue and that's one of the main issues that’s actually driving the movement to shut down the District.

If you talk with the women who are working there, they'll tell you a very different story. They'll say yes, there is trafficking and they need to shut that down, but a lot of the women are there on their own and are making their own choices. I think there's still a lot of misunderstanding and miscommunication about who these women are and why they're there.

You mentioned that the city is trying to shut down the District, and you address some of this in the book’s intro. I know that the country’s cannabis culture has changed a lot, too. What do you think of the growing movement to decriminalize other vices in the States, and how do you think that relates to the Netherlands' recent approach?

I think it's really heartbreaking when you go to Holland and you see where they're at now compared to where they were 20 years ago, especially when you see where the rest of the world is. They're definitely moving in the wrong direction.

When you look at cannabis and you look at prostitution, they're similar in the sense that you can't contain it. You can't put it in a box and the more you struggle to do that, the more you just push the industry out to the fringes in a way that causes more harm to society than good. This is not a book where I'm celebrating prostitution, but look at the ability of a woman to work in a window with security and safety and regulations, as opposed to what happens when these windows aren't there: having to work in brothels or on the streets where their safety is in danger. The fine line between the two is that by having a Red Light District, it makes that world so much more accessible, and I think that's one of the dangers when you romanticize this world. It shouldn't be romanticized. It's a part of the world, it's a part of human nature.

When it comes to the cannabis culture, it's sad. The Grasshopper, which is one of the biggest coffee shops in Amsterdam, is being shut down. Also, coffee shops were able to stay open until 3, now the vast majority of them shut down at 1 o'clock. So many of the great growers have left. The whole culture has fled and shifted to Spain, Colorado, and, of course, California. So the whole culture of Amsterdam has really changed. It's definitely moving in the wrong direction. All it does, as we've seen in America and elsewhere, is that the industries don't go away, they just shift. They take different form and they shift to places where you can get into a lot more trouble and get hurt, to be honest.

.jpg)

Is there anything else you'd like to add about Amsterdam Exposed?

With the book, I really wanted to create an experience for people who smoke. I think people in the cannabis community would enjoy it because it captures my transition from someone who never really smoked that much before I went to Amsterdam. It shows how innocent the plant really is. It's not a big deal. It's just a part of life. It shows that you can go to an Ivy League school and smoke a joint and be fine.

I hope that as the months and the years go by it's something that really finds a place within the cannabis community. It's as much a cannabis story as anything else. Going to another world and finding the plant really helped me find balance and peace and perspective and the ability of perception, too. [Cannabis] wasn't a huge part of the book, but the moments where I talked about it were very strategic and very important. For me, one of the things about cannabis that’s so transcendent is that it's spiritually meaningful. It can help people quiet the mind and experience things in a way that one might not be able to without it. I think the book really tries to capture that energy.

Purchase ‘Amsterdam Exposed’ on Amazon and visit http://www.amsterdamexposed.com for more

Follow Patrick Lyons on Twitter.