Photo via Nastasic

Is marijuana medicine? Is it addictive? Does it cause traffic fatalities? Can it stop the opioid epidemic? Will it kill my sperm count and give me breasts?

To answer these questions (well, except the last one), the University of California at Los Angeles created the Cannabis Research Initiative (UCLA-CRI), a multidisciplinary program staffed entirely by medical doctors and academic researchers. Their research will uncover cannabis' roles in psychiatry, neurology, infectious diseases, hematology, cancer, and the behavioral sciences.

As weed is now legal in America’s largest state (and one of the world’s biggest economies), researchers, policy makers, and medical professionals are wondering what's in store for a liberated but somewhat uncertain future. Luckily, as the stigma of cannabis use begins to fade away, it's becoming easier for universities to study marijuana's effects on society at large.

To find out what the project is up to, MERRY JANE called Dr. Tim Fong, who sits on the executive committee for UCLA-CRI alongside Drs. Jeff Chen and Peter Whybrow with Professor Christopher Evans. Fong is a clinical psychiatrist with a specialty in addiction. He's been a part of UCLA's Department of Psychiatry since 2002, and he currently serves as the director of the UCLA Addiction Medicine Clinic and co-director of the UCLA Gambling Studies Program.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

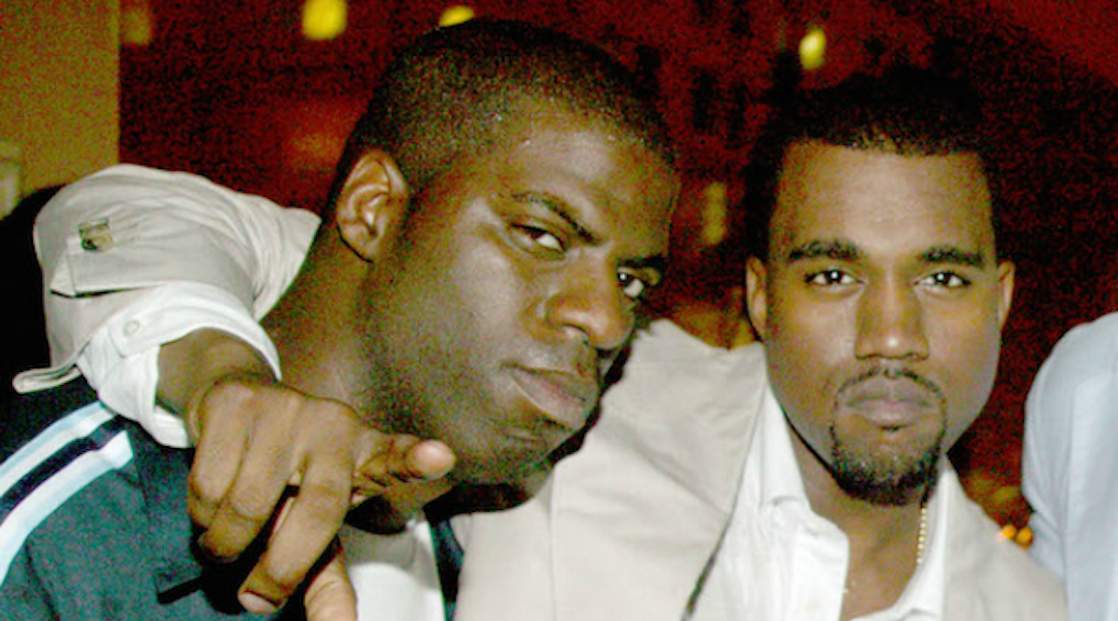

Dr. Timothy Fong, UCLA Cannabis Research Initiative

MERRY JANE: Can you start by giving us a little background about UCLA's Cannabis Research Initiative?

Dr. Tim Fong: When legalization passed here last year, it became very clear to us at the Department of Psychiatric Medicine that we needed a true scientific approach to understanding cannabis. We've seen what happened in Colorado and across other legal states, and we realized we needed to centralize our work at UCLA to disseminate information to our faculty and to the public. Our mission is to use the power of science to understand the impact of cannabis on the body, the brain, and the mind.

My specialty is on the addiction side. Not only on how to prevent cannabis use from becoming an addiction, but also how to treat patients who are already impacted by addiction, to develop more effective treatments to cope with cannabis withdrawal or cannabis-induced psychosis.

For me, as a psychiatrist, this is what I'm seeing in the clinic. As a parent, this is something I'm seeing as a major issue in our city. It really dawned on me and others that we need to get in front of this issue rather than react to crises as they emerge.

Cannabis addiction is a highly controversial topic in the cannabis community. Many advocates and activists say it's a myth. You're saying it definitely is an addictive substance, but from your professional experience, how addictive is it?

The science is crystal clear here. We have a large database across the world that shows when you start smoking cannabis there's roughly a 9 percent chance you'll get addicted to it. When you drink alcohol, or start smoking cigarettes, or start using cocaine, that chance gets a little higher. But 9 percent is not zero.

We also know that, if you start smoking [cannabis] before age 21, that chance is higher, around the order of 20 percent. How I know it's addictive is when patients come in and they tell me their life story, and we pinpoint where their life started to become harmed, or when they stalled in development, or they have physical problems, or they have difficulties just functioning and experience a lot of distress. Oftentimes it specifically begins with cannabis use.

What would you say to advocates who argue that it's just a plant?

It's a fascinating idea, but I think about it very simply. Cocaine's a plant, opium’s a plant, alcohol comes from a plant, nicotine comes from a plant — all of these things have been clearly shown to be addictive through science. It's the same thing with cannabis; it's a plant. The neurobiological data shows it affects the same exact brain regions as a lot of other addictive substances.

But there are also the human stories. It's the people who come into our offices, emergency rooms, and hospitals, and it's very clear: they have the same condition of addiction as someone has with alcohol or cocaine. They're experiencing the same symptoms of urges and cravings and the inability to stop, tolerance, withdrawal, and their lives being damaged.

Yet, as you noted, this addictive potential doesn't apply to most people.

I have a very simple motto: if cannabis use makes your life better, if it brings you more joy, more opportunities, and more fun, then that's not an addiction. But if repeated, ongoing cannabis use causes damage to your body, your brain, your mind, your family, or society, then it's not a fun hobby. It's clearly something else.

When we look at national surveys, we estimate that maybe 6 to 8 percent of the entire country may have a harmful or addictive relationship with cannabis. That may seem like a low number — and it's lower than tobacco or alcohol — but it's certainly a lot higher than cocaine, opiates, or heroin, and I think that's the real shocking part.

We see alcohol, heroin, and cocaine's effects are much more obvious to the naked eye. With cannabis, it's not always a simple matter.

Your project at UCLA is focused on addiction and craving sensations. However, there are a lot of people looking at cannabis as a way of curbing the opioid epidemic. Do you believe cannabis could alleviate the epidemic, or that it could work as an exit drug?

As a potential treatment, it's interesting. But we don't have nearly enough science to back that up. That's the entire purpose of getting some objective science behind it. Let's take the myths out. Let's take the cultural stereotypes out. Let's take all of that out, and definitively test this in a reliable, safe way.

I've had several patients who were able to manage their chronic pain with cannabis in lieu of opiates. Could they have managed their chronic pain without cannabis? These are the questions we're looking in to. Without a doubt, though, THC, CBD, and the other hundreds of cannabinoids are incredibly fascinating, we just don't have the knowledge right now.

Legalization just rolled out in California. Have the changes in regulations made your research easier or has legalization hindered it?

It's too early to tell. Our medical school and our psychiatry department said, with open arms, "Yes, we want to build a cannabis research initiative. We're going to support that." That wouldn't have been true 15 years ago. If I went to my department chair back then and said, "I want to study marijuana and cannabis," he would've said, "Yeah, I don't think that's a good idea."

Just by the very fact that we're opening it up is terrific. UC Irvine and UC San Diego are also expanding their cannabis research, and that suggests we're getting some smart people who are going to look at this issue that's been neglected for a while.

What are the initiative's future plans? Will it remain focused on addiction or will it branch out into other topics?

This is where our research initiative is wide open. We have a budget for a whole host of other researchers, including neurologists who are curious about its use in seizures. We have chronic pain specialists who are curious about how to use it for pain conditions. We have policy researchers who are fascinated by health and economic impacts from cannabis. We have pulmonary researchers who are interested in knowing if cannabis can lead to pulmonary diseases after ten, fifteen years of use. We have researchers who want to know what happens to the brain when people ingest cannabis in different formats, for instance vaping versus edibles versus inhaling flower. We don't know. We have people looking at CBD for anxiety, sleep, and depression. There are a lot of different topics.

For example, we're in early discussions with a medical marijuana clinic right now. One of the questions I have is: What kind of people come to these clinics? How well does marijuana help them? How much is it just a false cover for recreational use? Should there be better standards for medical marijuana dispensing? What happens to the medical marijuana industry now that recreational [cannabis] has been legalized?

The only problem we have right now is that there are almost too many areas to research. For now, we're focused on tackling the core questions, particularly those that pertain to our state.

Where does the Cannabis Research Initiative's funding come from?

Starting in July, we've been funded by an endowment from our Department of Psychiatry and the UCLA School of Medicine. We don't sell cannabis or anything like that. We're reliant on philanthropy. We're reliant on grants and non-profits that are interested in our research. We're going to try to rely on NIH funding. It's a wide variety of inputs.

The state of California also said they'd put aside a significant amount of money for research into cannabis and the impact of cannabis on California. But those mechanisms are not yet established.

The diversity of funding is important, too. As a scientist, it's important to be fully transparent. I wouldn't want funding from just a single source; we want it from a variety of folks with a variety of questions in a variety of areas they want us to study.

Are you dispensing cannabis to research subjects? If so, where does it come from?

At this point, we're not able to dispense cannabis just yet. To study cannabis in a controlled laboratory setting you have to have a Schedule I research license from the feds. We don't have any faculty researchers right now with that license.

We don't grow the marijuana here on campus. We don't have cannabis inside our offices. That's always a misconception people [have] about us. We're following the federal rules first, and we're following the state rules second. Fifteen years ago, when we did cocaine and amphetamine research, I administered [intravenous] cocaine to men and women with cocaine addiction. It can be done; it just has to be done properly and with approval from the university, the state, and the federal government.

Have you applied for the DEA's Schedule I license for cannabis?

Not yet. Again, those Schedule I licenses are tied to a specific protocol. Let's say I want to administer cannabis to patients versus a placebo for chronic lower back pain, and I wanted to use a sativa extract. I would apply specifically for a Schedule I license from the feds for that particular protocol. It's not like they'd grant me a license to just run around and purchase all kinds of cannabis and do all kinds of strange things with it. Everything is highly monitored with all sorts of questions: where do you store it, how do you safeguard people, et cetera. You can do it; it just requires a lot of time.

Part of the reason why our researchers didn't do that is because there weren't a lot of calls for proposals to research cannabis, and also because it hadn't reached this level of societal impact and discussions unlike, say, amphetamines or alcohol.

If you're not administering cannabis to patients, how are you getting data for the addiction studies?

That's a fascinating question. One way is we can partner with a medical dispensary and get data from their customers, or from patients who go to medical marijuana clinics. Or we can look at state data and assess how many cases are coming in due to cannabis use. Inside our UCLA health system, we can access electronic records from before and after legalization. We can recruit folks to come in for a clinical trial. Or we can contact California's Department of Highway Transportation and look at accidents and DUIs related to cannabis, and tie those bases of information into other sorts of trends.

One of the areas we're looking at is all of the substance abuse treatment programs in California, and because that information is centralized, we can ask what percentage of people are coming in reporting they have problems with cannabis? We can compare that data with responses from before legalization and after legalization.

How do you foresee your research being used for regulations or policies?

People always ask that; they always ask, "So what? What's your research do?"

To me, it answers essential questions we have about cannabis. How it impacts the world and people. As a physician, it's my mission to reduce harm and suffering, to make people's lives better. This is a substance that has great potential to make many lives much better, but it also has the potential to hurt a lot of people. Those are the questions we're curious about: how will our society look like now that cannabis is much more available than it was several years ago? Those are the so-whats. It's about saying, “This is our home, this is how we're shaping our society. How does this plant impact everything?”

For me, I want to know what are the environmental impacts of growing cannabis in terms of water usage, pesticides, and food production. That's not my area at all, but I'm curious. I'm a California citizen, I have a family here, I want to stay here, and I want to see our state continue to do well. But one of those questions is does cannabis make our state better, or does it make it a more challenging place to live.

That's one of my questions to you: Do you feel like Colorado is a better place to live now compared to pre-legalization?

Overall, yes. Definitely. I've seen our economy boom. I see construction everywhere now. No one gets busted just for possession anymore. But there have been some issues. Our traffic has gotten crazy. In some areas, violent crime rates have gone up, because so many people moved here all at once.

We do have some problems, but those problems largely stem from the fact that cannabis is still federally outlawed, and all of the states surrounding us are still operating under prohibition.

Finally, cannabis is getting the attention it really does deserve. It's an important, legitimate substance in our country, and it's become a permanent part of our culture.

If you had one last thought to leave with our readers, what might that be?

I have a clear theme for all of my lectures: no cannabis for anyone under 21. All of our data clearly highlights this.

For instance, my niece, who's 15, visited for Christmas and kept talking about weed. She gave me weed sunglasses. And I'm like, "Hold on, what's up with all this? Have you tried cannabis yourself?"

She says, "No, but I'm going to." I asked if her parents knew, and she said, "I don't care, because everyone's doing it already." To me, as a parent and as a scientist, that's my number one thing: no cannabis for anyone under 21.

Number two: Respect the power and potency of this plant. This is an amazing product. When I was in college in the mid-1990s, none of this technology existed — dabbing, vaping, capsules. Not even close. That's why I say we have to respect the power and potency of the plant. In order to do that, we have to really think about this in a thoughtful and safe way. If cocaine or amphetamines or even heroin were legalized, there'd be much tighter regulations on those substances. But because cannabis has this underlying, false perception over the last 30 or 40 years of, "Hey, it's just a plant, it's okay!" people see it as no big deal.

Does your rule include medical use for kids?

Actually, no. But, we need true science to guide us for patients under 21 to be more respectful. Obviously, things like pediatric seizures, pediatric pain, multiple sclerosis, spasticity — if it's become very, very clear, beyond a shadow of a doubt — that cannabis would help with those medical conditions, then absolutely, I'd say, let's use it that way.

Just no recreational cannabis use for anyone under 21.

If you'd like to contribute to UCLA-CRI's research efforts, you can donate to them here.