All photos courtesy of Ralph Friedman and St. Martin's Press

In the 1970s, the South Bronx embodied the widespread chaos that had infected New York City. It had a reputation for crime, violence, and, at times, was literally on fire. Locals used to call the area “Fort Apache,” due to the borough being viewed as hostile territory. The NYPD’s 41st Precinct was based in the Bronx, and the area was known, among many worrisome traits, as a heroin hot spot, as well as the aggravated assault, rape, robbery, murder, and arson capital of America. Over 40% of the South Bronx was burned or abandoned between 1970 and 1980, culminating in Howard Cosell’s World Series outburst, “The Bronx is burning.” This was the world where Detective Ralph Friedman would become an NYPD legend.

With a resume filled with performance statistics that a whole unit couldn’t match — 2000 arrests, 105 off-duty arrests, 15 shootouts, eight criminals shot, four killed — Friedman has seen some shit, and he’s one of the most decorated officers in the history of the NYPD. During his 14-year career, Friedman was a super cop of unparalleled stature, a crime-fighting machine at a time when organized crime still reigned supreme in parts of New York City. He was a Robo-Cop for the disco age, if you will. In Street Warrior: The True Story of the NYPD’s Most Decorated Detective and the Era That Created Him, out now on St. Martin’s Press, Friedman recounts the harrowing trials and tribulations he experienced while wearing his uniform. The memoir is filled with war stories and anecdotes about the bygone era of policing, a time when cops didn’t have to wear body-cams or worry about being politically correct.

As someone who was incarcerated for a nonviolent drug offense, I wanted to talk with the detective about his current perspective about the War on Drugs and mass incarceration. With marijuana being decriminalized in New York City, as well as the problems of racial profiling, police brutality, and the fallacy of the broken windows theory coming to light in recent years, there’s been a big movement for change, even though there is still a long way to go. Friedman’s account of the NYPD is from a different age, and he’s unapologetic in his views — many of which feel outdated in today’s era of community activism and protests against police abuse. Though offering an adrenaline-rush for true crime junkies, Friedman’s book fails to address many of today’s most pressing issues in favor of one cop’s vigilante view of criminality.

MERRY JANE chatted with the old-school police detective about why he became a cop in the first place, what he thinks about police using deadly force, and why police forces in this country, like the NYPD, are embroiled in controversy. Plus, we talked about if his loose cannon police tactics from yesteryear would have landed him in hot water today.

MERRY JANE: You’ve definitely had a super cop career, no doubt, but let’s take it back to the beginning. Why did you become police officer in the first place? What was the motivating factor?

Ralph Friedman: I never thought of being a police officer. I was out on a Friday night with a couple of friends and I asked them what they were doing the next day. They said they were taking the police exam. I said “You’re kidding me,” and they said they weren’t. It was a walk-in test at the high school I graduated from. I said to them, “Listen, why don’t you knock on my door and if I wake up, I’ll go.” I never thought about becoming a police officer. I had no friends or family that ever were. But they knocked on my door and I got up and took the test. I had a good job as a furniture mover, but there was really no advancement. I’d be carrying the same couch on day one as I would 20 years later.

I didn’t feel like a super cop. Ninety-nine percent of the officers would have done the same things I’ve done, but I just happened to run into [trouble] more. I was out there all the time and I really enjoyed the job. I found this new culture, this new life. The police department was very tight then. There was a lot of camaraderie. I always made myself available and I always wanted to be out there — I enjoyed the job that much. My life was at risk, but I always came out on top. I enjoyed the job at all times, and got a lot of bumps and bruises along the way, but thank God I wasn’t killed.

What was it like revisiting your career in the book?

The ‘80s were really tough. I was in a lot of serious, dangerous, life-threatening situations. I never discharged my gun without being totally justified. If my life or my partner’s life was on the line, we had to do what we were trained to do. I loved the action. I felt I was helping people in the ghetto communities. I felt I was making their life safer, protecting them from predators. I like to be involved. I like to get involved and take control of the situation and help whoever needs help. I enjoyed it and I got a rush out of it. You know what drug I’m addicted to: adrenaline. The police on the front line are the grunt soldiers. They take it from all sides and they still do their jobs. I was in 15 gun battles and I shot eight people and killed four. In the book, it details how I was shot at by police, too. There was a riot scene and I responded and I was under fire by the police.

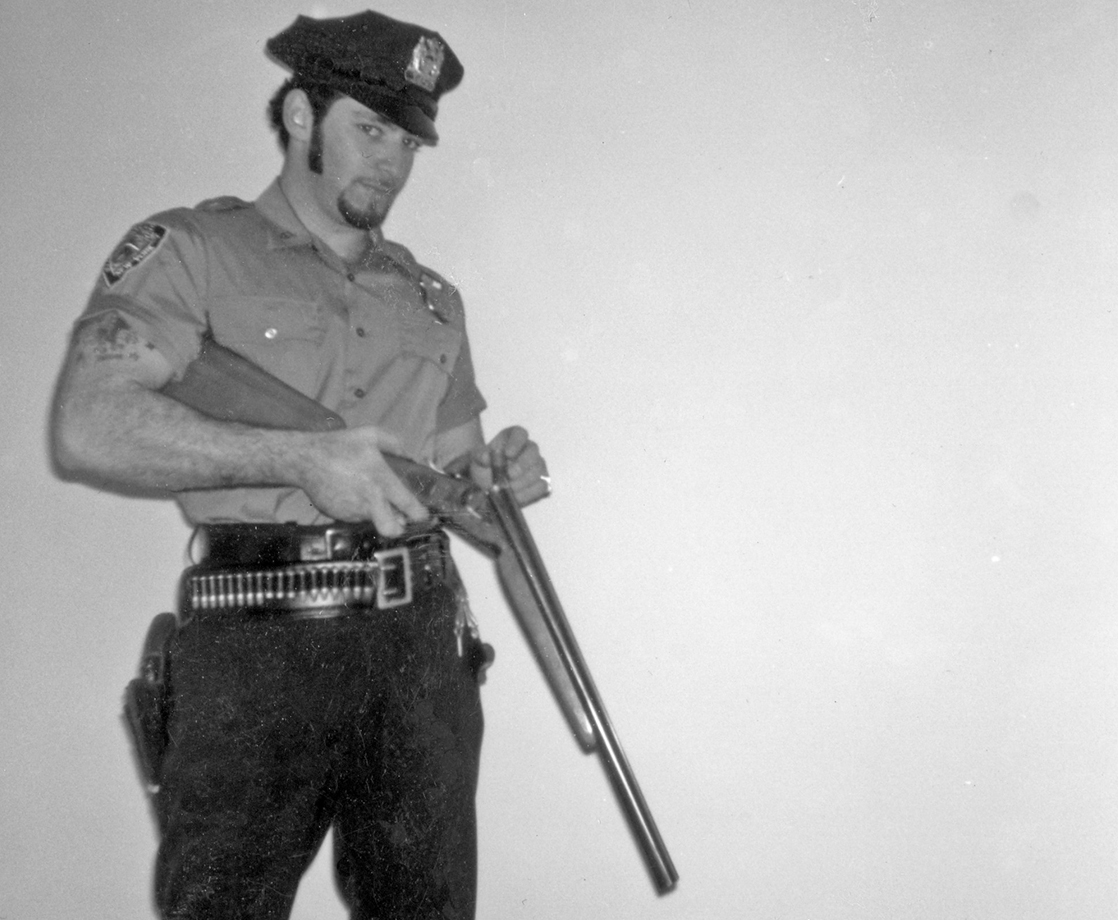

Promotion picture taken at Big Joe’s Tattoo Parlor. Photo by Big Joe, courtesy of Ralph Friedman / St. Martin's Press

How was police work different when you were coming up in the 1970s and into the 1980s, as opposed to to now? Was it two different worlds, or can you make a parallel?

It was a different era. A different time. It was very violent back then. Not that officers don’t face violence now, but it was like a Wild West show in the Bronx then. There were shootouts on the streets all the time. People were getting robbed. The city was in dire straits. It was heading for financial ruin. Drugs were rampant, and muggings, robberies, and purse snatches were up. Today, it seems like there’s more control. It was almost out-of-control back then, and the police were just holding the line.

Policing has changed over the decades. The biggest thing to change policing was the cell phone with cameras. The police are in the public eye. When I started, it was the 1970s, so we’re talking almost 50 years ago. In every profession, the job has changed. DNA [testing] wasn’t even invented then, and now they track bullets by trajectory. Communications are way better. It’s a totally different job with the technology they have today. It’s like being on another universe, actually.

How do you think racial profiling and the use of deadly force, as we’ve seen in recent years, has affected the public’s perception of police?

I never came across that throughout my whole life and career. I didn’t work with people that were racist and I never saw it. I had a black partner. I had Hispanic partners. We mended out the law equally and justly. I just didn’t see it that way, and I was very involved. I was against perpetrators. I didn’t like people that prey on the weak, the old, females, or infants. In my career, they didn’t call it racial profiling.

If you worked in a busy house like Bedford-Stuyvesant, the numbers were always higher. Officers would stop more people on suspicion of carrying a weapon or drugs because it’s a busy house. We all agree that’s there’s more crime in some areas than others. It can be a Spanish neighborhood, a black neighborhood, or a white neighborhood. But in all those areas, no matter how bad, they’re decent, hardworking, tax-paying people that need and deserve protection. They get more protection, because there’s more police, who happen to do more stops.

The police department takes deadly physical force very seriously. When you do take an action, it’s investigated by numerous authorities. If you happen to shoot somebody or take a life, you have to go before a grand jury that’s made up of civilians and they judge if you were justified or not, or if there’s enough evidence to take you to trial. You’re also investigated by a shooting team, Internal Affairs, and the DA’s office. Sometimes there are tragic errors — just like a car or plane accident — but checks and balances are in place. I’ve shot eight people, which resulted in four dying, and I was always justified doing exactly what I was trained to do. Sometimes you have to take a life to save a life.

Ralph Friedman and Timmy Kennedy with evidence taken from arrest of Jamaican gang members (August, 1982)

What do you think about the fallacy of the broken windows theory?

If people commit small crimes, they’ll also commit large crimes as they move up. Where do you draw the line? Today one of the top things is noise complaints and loud parties. One person in a building is having a good time, but at the expense of all his neighbors in the building. At some point, the people throwing the party are going to want to sleep and they’re not going to be happy if someone else is throwing a party then. You have to be considerate of everybody around you. It’s the society we live in and minor laws are what they call the quality of life laws. You have to enforce them too, but policies come down from the mayor.

Do you think mass incarceration is a result of locking up people for nonviolent drug offenses?

People are disobeying the law more, so there’s going to be more people in jail. Now, as far as violent crimes, I personally feel penalties should be based on your criminal record. If you commit a lot of burglaries, then chances are you’re going to commit another burglary. Today, more people look at the criminal’s side — yes he’s in jail, but what about all the innocent, hardworking people that you’re protecting this person from? If you can’t get along with society to a certain degree, then you have to be separated from society. As far as non-violent crimes, it would depend on what [the citizen’s] history is. If you’ve got a guy shooting ten people on ten different occasions and then one time you grab him for something non-violent, he should still go to jail. He’s already proven that he’s somebody that cannot live in a normal law and order fashion.

In the ‘70s and ‘80s, weed was commonly sold out of a lot of bodegas throughout the city. What was your relationship like with marijuana dealers, and how often did you arrest them throughout your career?

When I started policing in the 1970, I never saw any drug but heroin. It was so popular in the ghetto precincts at that time. But in 1975, when I got promoted to detective, I went up to the North Bronx and I started seeing weed, pills, and coke. Back then, marijuana wasn’t tolerated like it is today. I don’t do any drugs, and my feeling is I don’t want to be around anybody that does, but I do realize that marijuana is very good for medical purposes. I’ve come to accept that. But back then the laws were different and I was still being paid to enforce the laws. I’ve definitely made marijuana arrests.

Mayor Abe Beam awarding Ralph Friedman the Combat Cross for actions taken on November 19, 1974. (Photo taken on May 19, 1975)

You retired in 1984 due to a work-related injury, but why did you wait until now to write a book about your career? What influenced your decision to put your life story out there?

The police have taken a lot of heat in the last few years. They’ve been micromanaged by the public, by the department, and by the politicians and media. It seems like they’re being attacked from all ends. I wanted to show that the police are really out there to help the public. They serve everybody and it seems like the people they serve the most hate them the most. There are people who appreciate the police, but they’re not loud and vocal like the ones who don’t like the police. I’ve been a police officer and I’ve dealt with other officers and they’re really sincere. They want to help people. They leave their families every day and come in and put their lives on the line.

Why do you think that police forces in this country, especially the NYPD, are so embroiled in controversy?

People see police on patrol laughing and joking. They see them sitting there having a coffee or getting a slice of pizza. But when the real danger occurs, it’s the police who run towards it when everybody else is running the other way. After 9/11, everybody loved the police and firemen. They were flying flags and it was all very unified. But it faded away. This book is dedicated to the police back then, now, and in the future. There are men and women out there that want to help.

Look at this poor officer that was just killed, Miosotis Familia. She was just sitting in the car and someone executed her for no reason other than she was wearing a blue uniform. You put your life on the line everyday — not only by stopping a criminal or engaging in a shootout — but by just sitting there. Sitting in your car wearing a blue uniform. What other profession has anything like that attached to it? Nothing, unless you’re overseas in the military or a war. I think everybody should be thankful that there are police out there, because otherwise it would be a jungle where only the strong survive.

"Street Warrior" is out now, order a copy through St. Martin's Press here

Follow Seth Ferranti on Twitter