I Am Not Your Negro, a film by Raoul Peck based on 30 pages of notes by acclaimed author James Baldwin for a book he started in 1979 but never finished, is here at a time when the front lines that divide this country are once again visible and impossible to deny.

Baldwin, who died in 1987, had intended to tell a story about America through the murders of three of his friends: Civil Rights activists Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr.

As demonstrated in his literature and in this film, Baldwin’s words are at times deeply moving, as should be expected from a man who knew all too well heartbreak, torment, and pain, but also love and hope. Samuel L. Jackson narrates, his typically distinguishable voice almost unrecognizable at first. The actor reads with just the right hint of melancholy, giving even the simplest of phrases the necessary gravitas.

Image via Magnolia Pictures

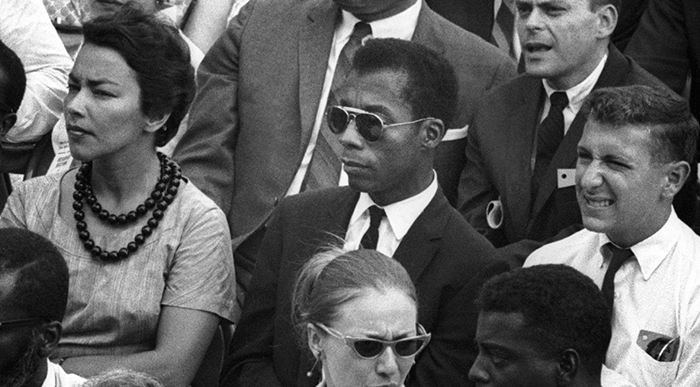

Jackson’s solemn narration fits in with the sadness that washes over the film, supported by the often anguished expressions on Baldwin’s face in old TV interviews and other archival footage. The author looks permanently teary-eyed, a furrowed brow chiseled into his features, as if the weight of the world is upon him.

His concerned countenance is evident during the debate with William F. Buckley Jr. at Cambridge University’s Union Hall in 1965. The concern is not for his pompous opponent but in trying to convey the black experience in America so others could truly begin to understand it. It was here where Baldwin famously said: “It comes as a great shock around the age of 5 or 6 or 7 to discover the flag to which you have pledged allegiance along with everybody else has not pledged allegiance to you.” He went on to add: “It comes as a great shock to discover that the country which is your birthplace and to which you owe your life and your identity, has not, in its whole system of reality, evolved any place for you.”

Image via Magnolia Pictures

As eloquent as these statements are, it’s what he said in between that perhaps connected with the audience the most: “It comes as a great shock to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, when you were rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians were you.” It’s not clear whether Baldwin intended to make the audience laugh, but there is a bit of gallows humor in such an observation. It also opens up a discussion about the way that cinema has powerfully impacted our perception of the United States as a bastion of overwhelming whiteness.

Backed by various film clips, Baldwin recalls being a child watching with awe beautiful white stars as well as being subjected to the black stereotypes that did not reflect his home life at all. He goes on to break down such films as The Defiant Ones (1958), Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), and In the Heat of the Night (1967), all attempts at making statements about racism, but aimed at appeasing white audiences, not black.

It’s in thinking about how much film has become a part of American life that we wonder about its profound influence on our collective subconscious. It’s entertainment, yes, but is it also indoctrination? For over a century, movies have taught the world that although they may play the villain from time to time, white people are always the good guys who save the day. They are the pure-hearted who believe in God and who can do anything. Like the Bible, movies have comforted white people, reminding them how virtuous they are, even if in real life they haven’t always been.

Image via Magnolia Pictures

Although he was not referencing the power of cinema, Baldwin’s assertion that “[a]ll of the western nations have been caught in a lie, the lie of their pretended humanism” speaks to a troubled U.S. history that witnessed the slaughter of a native population, the enslavement of millions for free and brutal labor, and a war with a neighboring country for the sake of taking their land, hostile acts that have often been reimagined in films as bravery, patriotism, and God’s will. It’s a reinterpretation that doesn’t take into account how a person can pose proudly in a photograph taken at the scene of a lynching, and how such heinous images could be turned into postcards.

The question remains: Have white people ever confronted their very dark past in any meaningful way? Some liberals acknowledge the inherent wrongness, but many white people explain it away as the sins of their grandparents that have nothing to do with them. But the roots of racism run deep. One cannot ignore that in some families this is a legacy that’s passed down through generations. One cannot expect that simply time, and nothing else, will erase its harmful hold on people.

“You cannot lynch me and keep me in ghettos without becoming something monstrous yourselves,” stated Baldwin. “And furthermore, you give me a terrifying advantage. You never had to look at me. I had to look at you. I know more about you than you know about me. Not everything that is faced can be changed but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Image via Magnolia Pictures

The unwillingness to admit the effects of slavery or white privilege—a term some whites don’t or can’t understand—makes it apparent that white people’s reality is not the reality of minorities. Baldwin explains the disconnect like this: “For a very long time, America prospered. This prosperity cost millions of people their lives. Now, not even the people who are the most spectacular recipients of the benefits of this prosperity are able to endure these benefits. They can neither understand them or do without them. Above all, they cannot imagine the price paid by their victims, or subjects, for this way of life, and so they cannot afford to know why the victims are revolting.”

It’s no surprise that Baldwin’s words fit with both images of the Civil Rights Movement and with the protests of today. But in this age of alternative facts, we should know that whites have lived an alternative history, one that explains why some of them believe blacks and other minorities only want free stuff and not freedom. It’s the history that’s up there on the big screen, where their heroes are always right.